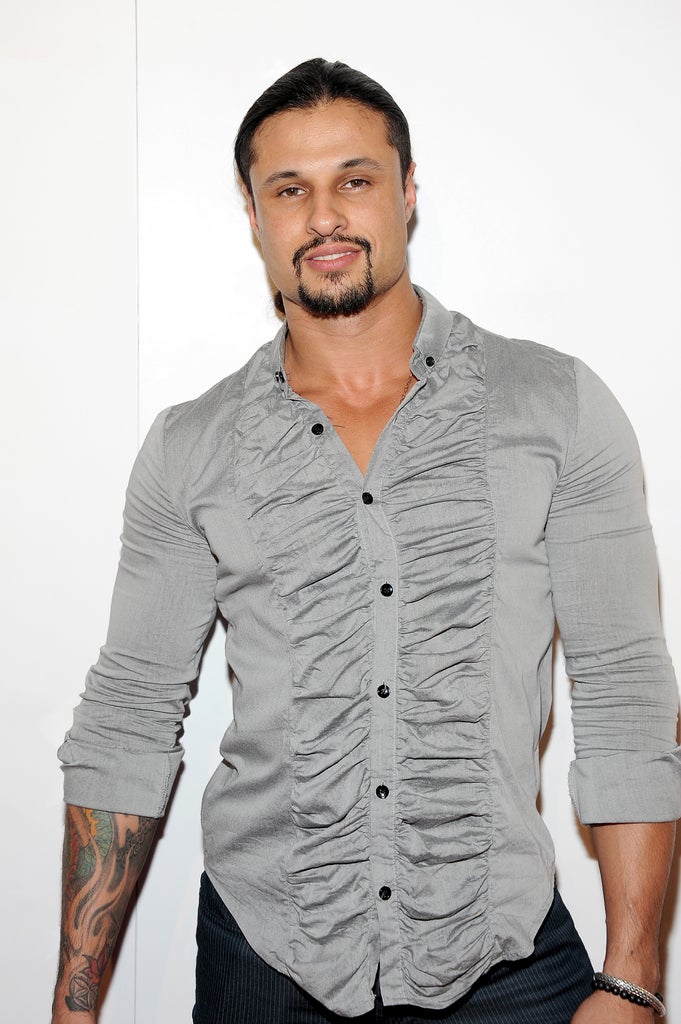

“It is going to sound insane because it is insane,” Akshaya Kubiak told the 911 dispatcher. It was 10 am on 16th July 2020, and Kubiak was calling from his Las Vegas condo; near him lay the dead body of a woman. “We took mushrooms together, said our prayers together, put on Avatar together,” said Kubiak. At 6’1” and 205 pounds, Kubiak was muscular and handsome; he was best known as the star of Showtime’s reality show Gigolos, where he went by the name Ash Armand. “I don’t know if you’ve ever done mushrooms before,” he said to the dispatcher, “but I was no longer in this reality. I was in trans-different realities. And then I saw the person next to me.”

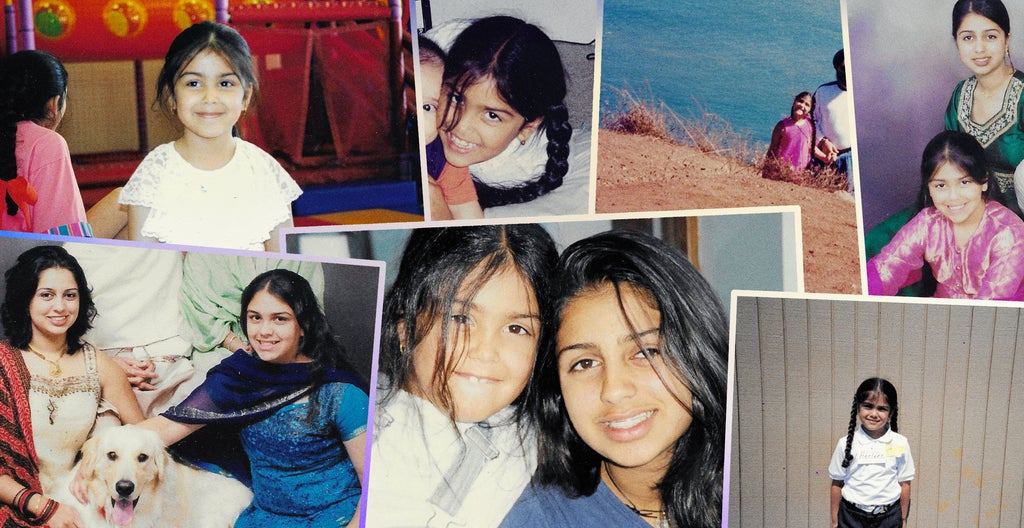

The person next to him was Herleen Kaur Dulai, a 29-year-old Temple University graduate with shiny black hair, large brown eyes, and a sparkling smile. She was gorgeous — she modeled occasionally — but was known for being shy and reserved. That may have been what drew Kubiak to her. “He would go after the new [models] that seemed lost,” said Leslie*, a friend of Kubiak’s. Dulai fit the bill; fairly new to Las Vegas, she’d moved there in 2017 to pursue a post-baccalaureate degree after having obtained her bachelor’s in biological sciences. While Leslie acknowledged that “moving to Vegas sort of feels like playing Russian roulette a little,” it seemed, at least in the beginning, that Dulai was avoiding the Vegas trap. A family friend of Dulai’s named Amrita described it this way: In Vegas, “Herleen broke free.”

Raised in California by an aerospace engineer father and a mother with two master’s degrees, both of whom had emigrated from India, Dulai was the youngest of three, and her parents’ favourite. They gave her the nickname “Happy Herleen” because she was always smiling. Although she was quiet around most people, Dulai was mischievous at home, always cracking jokes; and her emotions ran deep — she hid in a closet, crying, when her older sister, Aman, moved out to go to college; she wouldn’t go to the zoo because she couldn’t stand to see animals in cages.

Dulai’s strong emotions spoke to an underlying insecurity, though, according to Amrita: “She was very beautiful, but she spent most of her life feeling out of place.”

Soon after moving to Vegas, Dulai did something seemingly designed to combat both her emotional and physical insecurities: She joined A.C.E. Fitness, a gym which bills itself as “a life-changing facility that promotes unity and self-development through fitness” and prides itself on its close-knit community. Dulai’s time at the gym didn’t have an easy start. During her first training session with A.C.E.’s owner, Nick Lewis, she was so nervous that when he left her alone for a few minutes, he came back to find her curled up in a ball, shaking in the corner of the room.

“What’s up?” Lewis asked.

Dulai told him she had “headache issues… a tumor in her head… she needed to be in the dark.”

Whether Dulai actually had cancer is unclear. In a video from 2019, she sat on a darkened stage at the gym and told a small audience of around a dozen people that she had been “battling a brain tumour” and had gone through chemo. Yet Amy Elliott, a friend Dulai met at the gym in 2018, said that Dulai had a thyroid tumor, not a brain tumour. But, Lewis, who went to a doctor’s appointment with her, said that it wasn’t cancer at all. And, according to her sister, Aman, Herleen never told her family about the tumor. Other friends of Dulai’s didn’t mention the cancer, but did tell me that, in addition to being intensely withdrawn around people she didn’t know well, Dulai was battling depression.

Whatever her health issues, and despite the rough beginning, the gym quickly became a haven for Dulai. Lewis helped her lose 40 pounds in 30 days, he said, and in the process the two became close. She’d go to his house and hang out with his nieces and nephews, bringing them donuts. He went to some doctors’ appointments with her. Dulai started a youth training program at the gym, in which Elliott’s son enrolled. Eventually, she became a personal trainer, and the job agreed with her, opening her up and giving her more confidence.

“Whether it’s in a workout or in life, you’ve just got to keep pushing,” Dulai said in another video she made in 2019; in this one, she’s wearing black leggings and a half-zip grey top, a mountain looming in the background. “I’m trying to break out of my own shell. I have a fear of public speaking. But here I am in public, speaking.”

It was just a few months later that Dulai stopped working as a trainer for the gym; “she was falling out of love with it” and was “depressed,” said Lewis. According to Elliott, not long after that, in either May or June of 2020, Akshaya Kubiak slid into Dulai’s Instagram DMs. Or, perhaps, as a close friend of Kubiak’s said, Dulai contacted him first. Either way, Kubiak was a tough guy to ignore. He was an imposing figure: a 38-year-old, Fabio-esque hunk who looked like he’d walked off the cover of a romance novel thanks to his flowing hair, eight-pack abs, and sculpted physique — steroid-enhanced, according to friends — but still, he was distractingly handsome.

Kubiak was so attractive, in fact, that women paid $800 (£650) to spend two hours with him, $3,000 (£2,300) for an overnight date, and $25,000 (£18,000) for a week. For at least eight years prior to meeting Dulai, Kubiak had been working as a gigolo, starting when he was living in Miami with his then-partner and their son, and continuing over the years, including a short stint on Showtime’s Gigolos. Though he had a girlfriend at the time, Kubiak’s sex work was ongoing when he connected with Dulai.

But, was Dulai his client? Nearly everyone who spoke to me about this story had a different theory. Kubiak’s ex-girlfriend, Lisa*, who was living with him at the time, said Dulai was definitely his client. Lewis thinks so as well. When he and Elliott were cleaning out Dulai’s house after her death, they found an envelope with amounts written on them. “Ash, Rent, $2,700 (£1,900),” one read, another was for $4,700 (£4,000). But Elliott thinks the money wasn’t for sex.

“I know for a fact she wasn’t looking for no damn gigolo,” she told me, and speculated that Dulai was paying Kubiak’s dog walker while he was out of town. (Aman said she was given full access to Herleen’s bank account and there was no record of Herleen having paid Ash from it.) According to Elliott, Dulai rejected Kubiak when he first reached out to her, but he was persistent. Whether they were having a paid or unpaid relationship — or whether it shifted from one thing to another at some point — is unclear, but Kubiak’s parents say the two were communicating daily. In a matter of weeks, their relationship had gone from casual DMs to something far more intimate and intense.

Intensity was a quality Kubiak brought to everything he did. Raised by bohemian parents in both Maine and Japan, he and his two siblings were brought up in a spiritual tradition, focusing on Tantra. “From when he was a little boy, Akshaya grew up immersed in the healing traditions & philosophies of the East & West,” wrote his mother in a letter on Kubiak’s behalf to the court. Both his Asian-Indian mother and Polish-American father were teachers, and they exposed Kubiak to an “international crowd of scientists, poets and intellectuals, artists and academics of every stripe,” when he was a kid, according to his mum. Although his parents imply his childhood was happy, on an episode of Gigolos, Kubiak describes abuse: “I was hit by my godfather and other people, and I was quite harshly physically punished.” Kubiak’s father confirmed that the abuse happened while Kubiak and his brother were training at a horse ranch in Kyoto, Japan, though told me in an email he and his wife were unaware that “the embittered dispossessed farmer had started drinking heavily and became quite violent with Akshaya while ‘training’ him to become a useful regular at the ranch.”

Kubiak had not aspired to be a gigolo, and his path to Las Vegas was a circuitous one. At 16, he left school and took an apprenticeship to learn the ancient Chinese discipline of Qigong, which involves meditation, body work, and sometimes healing practices with herbs. He also studied Zen Shiatsu, a form of massage combined with philosophy. He worked as a model before moving back to Maine and getting his G.E.D. in 2000. While he was in his early 20s, he became a massage therapist, working in Costa Rica and Miami, and studying massage in Japan, Thailand, Europe, and India. He also trained a bit in martial arts like Muay Thai.

During this time Kubiak was involved in the psychedelic trance community, through which he and a few hundred other people would gather to drop mushrooms and sway to electronic trance music in the woods all night, said Mac* who organised many of the psytrance parties in New York and New Jersey that Kubiak attended. It’s “the underground of an underground movement,” Mac said, rave’s hipper, weirder cousin. One close friend from this time said Kubiak was “a kind, loving, innocent, playful, beautiful, genuine kid.” A picture of him from back then, during a psytrance event at the Pine Barrens — a heavily wooded, desolate area of New Jersey made infamous in an episode of The Sopranos — shows Kubiak mugging for the camera in a green tank top, mouth open, a wide smile on his face.

It might have been that very smile and openness that caught the attention of Garren James, the founder of Cowboys4Angels, an escort service that provides men for women. It was 2012, at this point, and Kubiak had moved to Miami to start his own massage business, Akshaya Touch. “Looking forward to joining you on your healing journey,” he wrote on the website, where he advertised a variety of massage techniques, including deep tissue, shiatsu, and “Akshaya touch.” He also claimed to do “in-call/out-call,” which are coded terms for sex work. Whether he was working as a gigolo at first is unconfirmed, but James would prove to be Kubiak’s entry point into reality TV.

After Kubiak had a successful six-month run working for Cowboys4Angels, James decided Kubiak should be on the reality show Gigolos, then in its second season on Showtime and filmed in Las Vegas. James served as a creative consultant for Gigolos, and insisted producers hire Kubiak even after he botched his audition. James knew Kubiak needed the money: He had a family to feed and he was barely eking out a living giving massages. Plus, James thought Kubiak would shine once he was actually on the show. His instincts were right.

“He was a good balance for the other characters. They made him out to be the zen warrior. You know, a peaceful guy,” James said.

Kubiak’s friends say the portrayal was accurate. “Ash was a healer. He healed me of vertigo. That was his purpose,” said Teresa*, a close friend of Kubiak’s. This was similar to his approach with his escort work, which he saw “as a healing modality, on the level of like, Tantra because of his Eastern background,” according to his Gigolos co-star Vin Armani.

But reality TV stardom changed Kubiak. He was insecure about how the other guys were more muscular than he was, Armani said: “Then, he started doing steroids, and he just got massive. It was almost too much.” Kubiak’s body went from Jason Sudeikis to Jason Momoa. His ego swelled, too. “Once he got that attention from the public, it was filling a void where he felt like, now I’ll be able to get my important message out to more people,” Armani said, noting that Kubiak’s drug use also grew more expansive in Vegas: “Marijuana, cocaine, and MDMA, are just everywhere. Ash had had a lot of experience, as I do, with all of those substances. In all of my interactions with him, I never saw him use anything to excess.” (Kubiak did not respond to requests for comment about his alleged drug use, nor to other requests for comments on this story.)

Instead of being focused on meditation and healing, Kubiak began partying on the Vegas Strip a lot with “‘bottle birds’ — the hot Instagram models that hung around,” Armani recalled. “Among that type of woman, Ash was very popular. He makes a great accessory, a great Ken to their Barbie.” Kubiak “stopped embodying something that I thought was unique and good,” Armani said.

A few months after the show ended in 2016, Armani invited Kubiak to a pool party. Kubiak brought along his then-girlfriend, Toochi Kash. At some point, Armani and Kubiak argued because Kubiak and Kash insisted on staging Instagram photoshoots and Armani told them to stop. According to Armani, Kubiak then challenged him to a fight. There was no fight, but Kubiak left in a huff, and the friendship never was the same, even though they continued to work together on double-dates.

By the time Dulai met Kubiak, he was a man whose time as a reality TV star was years in the past, and who was still doing sex work, according to Lisa*, Kubiak’s girlfriend at the time of Dulai’s death. According to James, Kubiak had also been fired from the Cowboys4Angels agency in 2019 because he didn’t properly represent the brand anymore. “After the show… instead of [Kubiak] being all about the client, it was more like, it’s all about me. And that didn’t really vibe,” James said. Kubiak was also broke, having apparently spent most of the money he’d earned from his time on Gigolos. He was living with his teenage son and Lisa in a split-level condo off Vegas’s Strip; his son’s mother lived on the East Coast.

Even though Kubiak was not appearing on reality TV anymore, he was still profiting from it, even if not financially: Gigolos retained a devoted fan base, and a clip of it was even featured in the 2018 Charlize Theron film, Tully. Kubiak tried to leverage his D-list fame to create an erotica website with his Gigolos co-star, Bradley; called Lexotica, it never took off, though some of the videos are available on his YouTube channel. One video received 2.2 million views. Kubiak also appeared in an episode of Vice’s Slutever in 2018.

But this wasn’t enough for him. Kubiak had “an addiction to attention and attention is a drug,” Armani said. Because of his level of celebrity, Kubiak got plenty of feedback on social media, but he was never satisfied. He would post progressively more provocative photos, Armani said, but “the problem is that you always have to give more, and you get diminishing returns, because it’s never worth as much. Now it’s 20 likes, now it’s 200 likes, now it’s 2,000 likes, now it’s 200,000 likes.”

Kubiak’s obsession with appearances and his online persona make it easy to wonder: Why was he drawn to Dulai? She wasn’t the type of woman he usually dated. He preferred to date wildly popular Instagram models like Kash, who has 5.4 million followers on the platform. Dulai only created an Instagram account because the gym made her. Some of their friends think it may have been their shared Indian heritage that drew them together. Others think it could’ve been more practical concerns.

“You have this guy who’s made all this money and [lost it], and then you have Herleen, whose family’s very secure financially,” Elliott said. “I feel like maybe that’s why he kept her around.” But Elliott can’t be sure because in March, at the start of the pandemic, months before she met Kubiak, Dulai stopped returning Elliott’s calls and texts. Elliott thinks that Dulai was trying to distance herself from the gym, where Elliott worked, but said that their friendship didn’t end on a “bad note… Herleen knows I love her. I know she loves me. But it’s just one of those things where you just need a breath of fresh air.”

Elliot wasn’t the only person from whom Dulai was keeping things. Lewis remembers helping Dulai out in June, a few weeks before she went to Kubiak’s house for the last time. Dulai was out of town, and she’d asked Lewis if a car her parents had bought her could be dropped off at his house while she way away. Lewis agreed, and remembers standing on his balcony seeing the car drive up; out of it emerged a guy who looked, Lewis said, like “Fabio,” clad in a muscle shirt, pecs rippling, hair flowing. This is weird, Lewis thought. He had no idea who the Fabio guy was, because Dulai had never told him about Kubiak. But he didn’t ask too many questions.

Dulai’s parents and sister didn’t know about Kubiak either, even though she talked to her parents two to three times a day and FaceTimed her three-year-old niece every night before she went to bed. To her family, Dulai seemed to be doing well. The only thing her sister Aman can recall that was odd was that Herleen mentioned she had started taking snake venom treatments.

Those treatments wouldn’t have seemed strange to Kubiak, who experimented with many alternative therapies. At the beginning of the pandemic, including when he was seeing Dulai, Kubiak had mainly spent his time holed up in his condo with Lisa, taking psychedelics and anabolic steroids, and working out, Lisa said. “He had upped his [steroids],” according to Lisa, because he was working on a pitch for a new TV show. Kubiak was also working on “an app for safe dating opportunities” and “a security service for women,” his parents wrote to me in an email. Then one day, in either May or June, he and Dulai travelled to Utah together and had a “life-changing experience” that involved a “spiritual breakthrough [that] made her remember something very traumatic,” Lisa remembered. Although “he seemed really excited for [Dulai]” to have the breakthrough, he was “stirring things up that wasn’t his job to stir,” she said.

A lot was being stirred up at the time, though; a month into his relationship with Dulai, Kubiak broke up with Lisa, telling her that he’d fallen out of love with her. She was blindsided and brokenhearted, but since she had nowhere else to live, she continued to stay with Kubiak.

On 15th July — the day Dulai came over, the day before she died — Kubiak told Lisa that “[Herleen] had some horrible dark energy around her,” and so Lisa left the house, leaving the two of them alone. And yet, that same day Dulai called her father. “She was happy, joking, and discussed how she was going to keep the family together when I’m not around,” he wrote to the court. She called Aman, who was eight months pregnant, and teased her: “She was telling me she didn’t like any of the names I had picked out and was making fun of me telling me what to name the baby.”

Not everyone thought things seemed normal with Dulai, though. Lewis, who was in Seattle, noticed that she had turned the location off of her business phone, something she did to indicate that he should check on her and make sure she was okay. “Are you good?” he texted. She didn’t respond.

Dulai went to Kubiak’s condo to retrieve his chihuahua, according to Kubiak’s parents, so she could dog-sit him for his upcoming trip to Miami to visit his ex-girlfriend and son, after which he planned to go to Jamaica alone. By the time Dulai went to Kubiak’s, small white backpack in tow, it doesn’t seem as if their relationship was romantic — but it was still intimate. Lisa said that Kubiak’s sessions with Dulai “had stopped being sexual” and had become about “soul-searching and healing.”

At some point during the evening, Dulai and Kubiak took mushrooms and climbed the stairs in the split-level condo, heading to Kubiak’s bedroom, where a chandelier dangled from the ceiling. Akshaya lit candles. They prayed. They watched Avatar.

“There was a struggle,” Kubiak told the 911 operator the next morning. “I temporarily lost my mind,” Kubiak told the dispatcher that Dulai had had a heart attack and that she’d had a history of cancer. Clark County Fire Captain Darren Lutes received the call a little while later, sending him to Kubiak’s condo at 8463 Blackstone Ridge Court. Lutes and his three crew members raced up the stairs to the primary bedroom, and there was Kubiak, pressing down on Dulai’s chest, his phone by his side. “One and two and three and four,” intoned the 911 operator as they coached him through his CPR, according to court documents.

But, what Lutes and his team saw when they arrived hardly looked like a heart attack. Lutes took note of Dulai’s “black and blue and swollen” face, blood surrounding her matted hair. Her ear was a giant bruise. Her body was covered in candle wax, as was the open suitcase that lay at her feet. Two candles stood near her body, their surfaces marked with bloody handprints. Near the suitcase was a black shirt and a ceramic statue, both spattered with blood. Lutes ordered Kubiak to “step out of the way,” so his team could “take over.”

“When was the last time she was even awake or talking?” a paramedic asked Kubiak.

He didn’t answer.

“How did she get the black eye and the facial injuries?” Lutes asked.

“She attacked me, and I attacked her,” Kubiak said.

Lutes then told Kubiak to “go downstairs and wait for the ambulance.” Lutes followed “to keep an eye on him” and make sure he didn’t flee. Soon after they got downstairs, the ambulance showed up. After the other group of paramedics entered his condo, Kubiak turned to Lutes and said, “Is she still alive?”

Lutes didn’t answer him directly. “I was trying to keep it light,” he said. Instead, he told Kubiak they were going to transport Dulai to a hospital.

“I did this,” Kubiak said. “Are the police coming?”

“They normally come to this type of situation,” Lutes said.

“When the police get here, I’ll surrender,” Kubiak told him, according to the grand jury indictment.

Dulai was never transported to the hospital. She was pronounced dead at the scene. Homicide detectives were sent to the house, and they found blood spattered inside the washing machine, and bloody clothes inside it. On the bathroom counter were bloodstains that had been watered down, as if in an attempt to wash them away, and a blood-soaked towel. “There was the appearance of clean-up is the best way to put it,” said a detective in the Grand Jury Indictment. A sheathed knife hung on the wall to the left of Kubiak’s bed. Detectives found a pocket knife, too. Dulai’s backpack was leaning against the couch. Mushrooms were in the refrigerator. When police inspected Kubiak for injuries, all they found was a small cut on the middle finger of his left hand and blood in his ear, which they assumed was from performing CPR on Dulai.

The full extent of Dulai’s injuries weren’t known until the forensic medical pathologist released her autopsy. Her body was covered in contusions. Her mouth was pulverized; her gums, shredded. Her teeth were broken, and fragments of them were found in her stomach. Her tongue, eye globe, scalp, brain, esophagus, arms, legs, and nose had hemorrhaged. She had aspirated some of her blood into her lungs. She had a fractured hyoid (neck) bone, and a broken rib. It was determined that the cause of death was blunt force trauma with strangulation as a contributing factor. She had MDMA, psilocybin, caffeine, and alcohol in her system. Yet Lewis had said she didn’t even smoke weed.

On 16th July, around 6pm, Aman was putting her daughter to bed in her home in a small city in Colorado, and getting ready to FaceTime Dulai as part of their bedtime routine. Dulai’s parents, who live with Aman, were in another room of the house, and had been trying to reach their daughter all day. Right before her granddaughter was tucked in, Dulai’s mom tried calling again. Finally, somebody picked up. “I know you’re calling your daughter’s cell, but it’s at the coroner’s office. She’s passed away,” the person said. As Aman was reading to her daughter, her parents entered the room. “Guys, what’s wrong? Are you okay?” Aman asked. Her mom whispered in her ear, “Herleen’s dead.”

“I couldn’t even comprehend what that meant. And I had a three-year-old next to me, so I had to pretend like nothing was going on, put her to bed,” Aman said.

That same day, Garren James, Kubiak’s old boss at Cowboys4Angels, got a call from a lawyer.

“Are you willing to help with Ash’s defence fund?” he asked.

“No,” James told the lawyer. “I helped make that guy a lot of money… But he’s actually done something against a woman, so there’s no way that I could have any part, helping that sort of defence.”

Soon after he talked to the lawyer, James got a call from Kubiak’s mom, begging him for money. “I felt extremely sorry for his family, and also the victim and her family,” James said. “I just, I couldn’t do it.” (When Kubiak’s 17-year-old son called for help, though, James said he did give him some money.)

The pleas for money continued. Kubiak’s parents sent James’s wife a link to the GoGetFunding site they’d set up for the legal defence. “Akshaya/Ash is being unfairly charged with a dreadful crime and without competent defense, he could spend the rest of his life in prison,” the site read. “Background: One morning in July a very sick young woman friend died in his home. He had called 911 for medical help and told authorities he felt responsible. The 911 phone staff coached him in emergency CPR which they continued together until the team arrived. Tragically she did not survive.”

James was horrified. “That [funding] page is despicable to me,” he said. Although the site has only raised $2,256 dollars to date out of the $60,000 being requested, it’s still surprising to many that James that it has raised any money at all. “Anyone who gave $1 to that fund should not get anything for Christmas, or get some coal in their stocking,” James said.

That’s a lot of people not getting anything for Christmas. Beyond Kubiak’s parents and the 21 backers for his funding site, letters to the court show that friends and family adored him. “Not once in the past 20 years have I known or seen him to express any form of violence, neither in word nor in deed,” wrote one friend. “There have never been any violent incidents in his life,” wrote his father. “It is utterly impossible to imagine him harming another soul,” wrote his brother. “To name Akshaya Violent or even capable of violence? Ridiculous. Impossible. Unimaginable,” wrote an aunt.

But, in cases of intimate partner homicide, not having a history of violence isn’t surprising. I described Kubiak’s case to Dr Jane Monckton-Smith, who has studied hundreds of intimate violence cases worldwide. “It’s just classic. It’s not unusual. And it is about humiliation, and setting the score. The violence used in intimate partner homicides is horrific. We’ve got this belief in our heads, which comes from the crime of passion defence, that is rubbish,” she said. Men she explained, claim: “I just lost it. I picked up the nearest weapon, gave her a whack, and oh, my God, I never meant to do it. I’m so good.”

Descriptions of domestic murderers as nice or non-violent appear in roughly half the cases of domestic murder Monckton-Smith has examined. She said, “Violence isn’t the biggest predictor” of intimate partner homicide. “The biggest predictor is them being very controlling, possessive, thin-skinned, jealous. That’s what makes people very dangerous.”

These are all qualities it seems that Kubiak had displayed, whether by getting into a fight at a pool party or threatening men who had dated his ex-girlfriend. And yet the support Kubiak has received, from college professors and artists, fans and relatives, people of all ages, has portrayed him as anything but the stereotypical abuser. But what is most surprising is how many women have publicly supported him, despite the fact that the crime of which he is accused is femicide. “Akshaya is deeply respectful of women… I strongly believe that whatever transpired must have been a grave accident,” one woman, a filmmaker and linguist, wrote to the court. In another letter, a director of public policy at the San Francisco Public Examiner’s Office wrote, “As a teenager…He…had an open mind, empathy for women and other oppressed groups, and understood the ways in which sexism has permeated our society.” An ex-girlfriend claimed, “Akshaya has a deep understanding of the power and sacredness of the feminine…I have never in my life felt unsafe or concerned about his behavior with women.” One of Kubiak’s friends told me he was a “sweet, soul, a tender loving man,” and she “wishes him the best,” although, she added, he “definitely killed [Herleen].” Another female friend said “he couldn’t hurt anybody” and “it’d be like your grandmother being charged with this crime.”

Perhaps this is the hardest part to understand: It is not that some of Kubiak’s defenders think he is innocent of killing Dulai, it is that they don’t think this makes him guilty of the crime. Some female fans have written similar comments on Facebook and Mac’s site (“accidents happen,” one wrote), and have sent Kubiak letters in jail. “I’ve lusted over this man for many years,” wrote one fan. “I do not believe he maliciously killed her. That goes against everything he is about.” Another wrote on Facebook: “he was zen yoga laid back anti-drugs guy he would be [the] last person to do this.”

A friend of Kubiak’s started an Instagram fan page “to pay homage to the man we all love.” It’s filled with thirst trap pictures of a shirtless Kubiak, striking poses in the desert, his snake tattoo winding its way from his pec to his crotch. “Pray for him,” many of the pictures say, “don’t judge.” There’s a link to Kubiak’s funding page, and information on how to write him in prison.

“The one thing that’s gonna get said is, Oh, my God, he was such a nice guy,” Dr Monckton-Smith said. “Well, how nice was he if used overkill on his [partner]?”

The power of the nice guy reputation must be strong, or why else would all these people support Kubiak? Perhaps they believe his family’s version of events. Until now it’s only been contradicted by a website started by Mac, who used to go to trance parties in the woods with Kubiak. On his site, Mac summarizes the Grand Jury transcript describing Herleen’s brutal beating and strangulation. In an email, Kubiak’s father referred to Mac dismissively as “a trancestream blogger whose [sic] been quite maliciously obsessing on Akshaya’s case.” But, more likely, the people who believe in Kubiak do so because they don’t want to believe that a man who spent his whole life building up an image as a compassionate, empathetic healer of women was, in fact, capable of the most horrific crime imaginable against a woman.

“I don’t know why we don’t believe men can be dangerous, because it’s been part of our cultural storytelling,” said Monckton-Smith. “Now, our cultural storytelling is the crime of passion. It says to women, ‘You know how dangerous men are, if you’re going to go off and have an affair, and he catches you, if he kills you by accident, that’s your fault.’ That’s victim blaming.” She pointed out, “We just seem very nervous of putting the gaze onto the ordinary man, because these are ordinary men. They’re not monsters. They’ve not got evil tattooed across their forehead. These are the men we are living with and working with.”

Perhaps the people who defended him were talking about the old Kubiak, pre-Gigolos. “The Ash right now is not the Ash I met in 2012,” said James. Fame changed him. “I think he was just dealing with something so deep that he lost himself,” said a close friend, who compared Kubiak to Dorian Grey, saying both lacked a soul.

For the fans, maybe the image Kubiak presented on TV was so compelling, so empathetic, that they can’t imagine that he would kill. A guy who claimed to be an avid meditator, yogi, and healer, and who spouted things like, “being in the business, you have to be a very, caring giving person”— how could someone like that batter a woman to death?

But if you watch Gigolos today, Kubiak’s appearances take on a different meaning. “Vampires really captured my imagination. They lust for blood but they also always generally hunt down beautiful women. I like the whole idea of having unlimited power,” he says in season 5, episode 6. Later in the episode, Kubiak, clad in plastic fangs, walks up to a wooden coffin, opens the lid and gazes into the eyes of his client, who is playing dead. After he lifts her out, she places her hands on the coffin and they have sex, red candles, dripping wax, surrounding them.

It’s impossible to know why Kubiak might have murdered Dulai, but Monckton-Smith says the most common predictor for intimate partner violence is a recent break-up, which Kubiak had — just not with Dulai. But, it’s not uncommon for men to project their anger from a break-up onto a new woman.

“The new partner can become the subject of the revenge and humiliation that they feel from the other partner that is still playing out, especially if it’s very close in time to a separation, because separation is the single biggest trigger for an intimate partner homicide globally the world over, by a long way,” she said.

Kubiak’s ex isn’t the only one who doesn’t know what else could have happened to Dulai other than what Kubiak’s being charged with. Kubiak admits he was there, and he said, “I did this,” but he has pleaded not guilty. Kubiak claimed that she attacked him first. In the writ of habeas corpus, Kubiak’s lawyer argues that “Akshaya and Herleen were likely…under the influence of controlled substances. Evidence further exists, as contained in discovery in this matter, that [Herleen] was the initial aggressor…Akshaya was in a condition wherein he reasonably believed under the totality of the circumstances that his life was in danger and he acted accordingly.” (Kubiak’s lawyer did not respond to multiple requests for comment). Armani said his first thought when he heard about the killing was that Kubiak “had tried to do some sort of exorcism,” by creating “a ritual space with candles,” perhaps even “candles on her chakras.” And a close friend of Kubiak’s said, “I don’t think ash knew he was killing her. He seen [sic] the demon, not her.” When I texted with the creator of the @asharmandfans Instagram, he wrote to me that “Akshaya is a healer…spiritually he healed her,” he wrote. “Death is not the end.”

Nine days after her sister was killed, Aman organised the funeral. “At eight-months pregnant, I had her body brought across state lines, viewed her disfigured face, found a restoration specialist and got the funeral arranged in a pandemic,” she wrote. Dulai’s face was so badly damaged that an expert had to be flown in from Missouri to do 15 hours of reconstructive surgery, so she looked presentable for an open casket. “The detective said the coroner couldn’t handle [seeing the injuries to Dulai] and they do this as a living,” Aman said. “I understood that I have to be the person to be strong for my parents.” Her father wrote, “It is like my heart is going to stop at any moment, but it doesn’t.”

A week later, Aman gave birth to a son she had “spent the last year going through IVF for.” He ended up in the NICU; she thinks it was because of the stress. In the delivery room, as the doctor whisked her baby boy away to the NICU, Aman and her husband gave each other a look, and they realized they had to name him what Dulai had wanted him to be named: Teghbir, which means brave warrior. “I feel like [Herleen’s death] took away from the emotions that you’re supposed to have when you deliver a baby,” she said. “I associated my son with her passing away.”

On 20th November, Aman spoke at Kubiak’s bail hearing in Las Vegas, as he watched from a prison video feed. “Just for reference, since you will never meet Herleen, people thought we looked alike. Our voices sounded similar and we laughed the same. But she was about two inches taller than me and markedly more beautiful,” Aman said, her voice cracking and shaking. “When she walked into a room, her aura of gentle lightness would fill all those present. When you look at me and at pictures of my sister’s body, it will allow you to visualize what must have occurred to create that transformation.” Kubiak looked on, “emotionless,” Elliott said. “The most common emotion after a murder like this… is relief. It’s not shame. It’s not guilt,” Monckton-Smith said. He was denied bail.

Elliott thinks that the qualities that made Dulai a wonderful person are what may have led to her death. “I don’t think I ever will meet someone with the biggest amount of love in their heart as Herleen,” she said. “When you do have such a loving heart that makes you instantaneously vulnerable.”

Kubiak’s trial is set for 4th Oct 2021. Aman wishes it would be over sooner. “Nightmares of the horror movie of her death steal my sleep,” she wrote. “I hear her screaming out for help and wake up drenched in sweat.”

Every night when Aman tucks her daughter in to sleep, she’s reminded again of her sister’s death, when her daughter tells her, as she always does: “I want God to send her back. I don’t love that massi [auntie] is an angel.”

*some names have been changed by request

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

A Timeline of Netflix’s Murder Among The Mormons