By the time Melbourne-based photographer Ying Ang gave birth to a baby boy in October 2017, her whole world had changed. “Devastated and in love,” she says, she entered the terrain of new motherhood. It felt like rushing – or falling – towards a new identity and a whole new way of being. She was experiencing postpartum depression and anxiety but when she tried to talk about it, she found that words couldn’t adequately encompass the totality of her experience. So she picked up a camera and began taking pictures. From these moments emerged her new photobook, The Quickening.

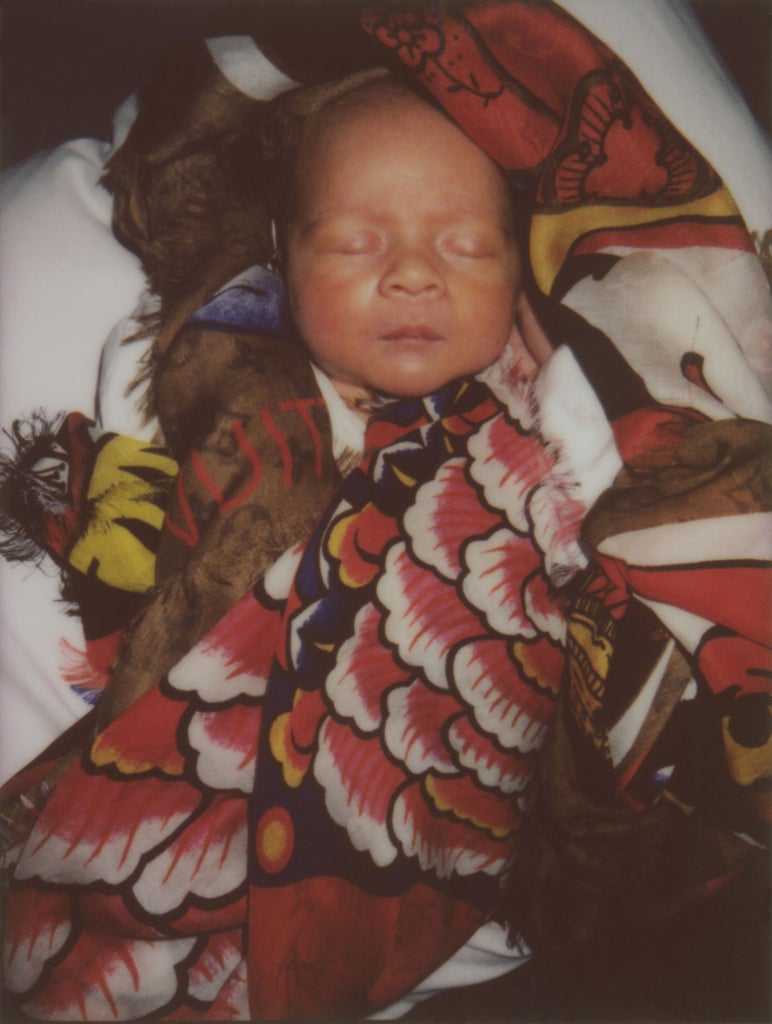

The pictures in The Quickening are a gorgeous cacophony of tender and tension-filled scenes interwoven with moments of luminosity which show how easily the lightest moments of motherhood can slip into the difficult ones (and back again). There’s a softness to the pictures, too – a dreaminess that feels like the first moments of waking up, where everything is a little blurry and sleep images linger. Ang worked completely intuitively with her camera because taking pictures was “a need that was propelled from the gut” during that period. “The moment, the camera at hand (of which there were several), the intensified feeling from the gravity of the moment,” she says, “all building to the variety of photographs that form the tapestry of my experience.”

Recalling that experience, Ang says: “It was profoundly disturbing, the way I couldn’t distance myself from my own experiences anymore. What I was feeling was literally moving inside me. The visceral nature of pregnancy began tying my sense of self, my identity, to the aches, movements, otherworldly sensations of my body and I was inescapably tied to the present, forced to live each moment instead of observing it from a safe distance.” She talks about the physical changes of pregnancy and motherhood – how small your world can become, how focused on domestic space, the repetitiveness of your days – as well as the changes that happen within. “In increments and then suddenly faster and faster, you become internally unrecognisable. The task of navigating this new geography, the new days and nights, how you eat, how you sleep, how you love – this seismic transition – is called matrescence.”

Matrescence is perhaps best described as the process of becoming a mother. It is an anthropological term used to encompass the complex web of physical, emotional and psychological changes a person can experience during that transformation. The process is different for everyone but for Ang, wrapped up in the brutal experience of postpartum depression/postpartum anxiety (PPD/PPA), it felt like “a sudden landslide” and subsequent wading through the rubble, picking up the pieces and rebuilding.

Ang was born in 1980 and grew up on the Gold Coast on Australia’s eastern seaboard. “I always felt like an outsider there and ultimately internalised that attitude and found solace behind a lens, cementing my position as an observer through life,” she says. “I moved through the world holding real life an arm’s length away, shying away from relationships and stable homes. The first major book that I made, titled Gold Coast, was shot very much in this way – cool, calculated and dry-eyed. Having a baby changed all that.”

Gold Coast confronted the insidious culture of crime and corruption that simmers beneath the all too perfect facade of her hometown. “A sunny place for shady people” is how she recalls the press referring to it at the time. The book won awards and was the last major project Ang worked on before she gave birth. Though of course all her work is autobiographical to some extent, The Quickening is an entirely more personal endeavour. Ang had taken pictures of herself in private before, and a self-portrait of sorts was included in Gold Coast – a picture from a newspaper article in which she is photographed as a witness to a double murder – but this was the first time she opened herself up to being seen – really seen, in all sorts of ways – by a wider audience, and by herself.

One of Ang’s most memorable pictures from the project is a close-up of her chest, with her baby’s arm reaching up to clutch a little fistful of her gold chains. “This was the first time I noticed that my baby would tug and pull on anything that he could grab…my hair, my clothes, my necklace, my glasses. He would literally hang off me, a permanent appendage. I remember reading that babies don’t understand that they are separate entities and that they even regulate certain physiological functions like heart rhythm and respiratory control on proximity with their mothers.” Another picture that stays with her is one of her breastfeeding, taken from the night monitor in the baby’s room. Grainy and monochrome, the figures of Ang and her son appear as if blended into one indistinguishable form as she feeds him. “I spent so much of my time in the first year of his life sitting in that chair, in the dark, feeling helpless, desperate and unseen,” she recalls.

The Quickening takes its name from an old term which, Ang explains, referred to the first foetus movements felt during pregnancy. “Before the advent of the ultrasound, it was this movement that would confirm pregnancy and declare the presence of life,” she says. “The word itself also means to accelerate, to move at speed and the sensations that come with that – the exhilaration, the loss of breath and, possibly, the leaving of things behind to reach a different place. From the moment of my son’s birth, I was plunged into a place where, like the landslide I reference, the ground beneath me gave way to form a new topography, suddenly and dangerously. A deep necessity to stay alive backed up against the need to die. That is what it felt like to mother with depression. Two continental shelves pressing against each other, buckling from pressure as ancient and inexorable as the gravitational pull of the sun. It felt impossible to experience and impossible to avoid at the same time. Excruciating fear and dominating love colliding.”

Ang deliberately edited the series of photographs she took to tell a particular story. “I am pointing at something specific,” she explains, “a darker, lonelier experience than the ones usually described outwardly in the public domain of the motherhood story. I felt entirely blindsided by the nature of my struggles in parenting a baby and was completely steeped in anger at the opacity of this transition in the arts, in the medical community and in public discourse. I was also angry at my own hesitation in making this work, that a story as ubiquitous as motherhood could find a place in the arts as something serious enough to consider as important. I place this squarely at the feet of the patriarchy – the gender politics of medicine and the resultant bias that leads to under-researched topics that are exclusive to females… The historical makers and gatekeepers of art minimising experiences of a classically female role, such as mothering, despite its profundity and outsize importance to humanity.”

After her time making this work – and living its subject matter day to day – Ang says she learned “that there is an incredible richness and multiplicity to the experience of mothering” and also a surprising unity. “Given the enormous diversity that forms the cultural background of how women go through matrescence, the thread that binds women through this experience varies in thickness and colour but binds together nonetheless. I have also learned that the patriarchal attitudes still left in place in our medical and social structures need to give way to provide adequate understanding and support for women who are having babies, in order to move some way into circumventing the devastating statistics that we have about PPD/PPA. One in five women experience it and it is also the leading cause of maternal death next to cardiovascular complications.” The true consequences of postpartum depression and anxiety are still not talked about – or understood – enough, in any context. Ang’s project helps those of us who haven’t experienced it to get some sense of what it looks like and how uneasy it feels to live through. This is profoundly affecting work about the way your identity changes when you become a mother and the psychological, social and physical toll that can take, in front of and away from the public eye.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?