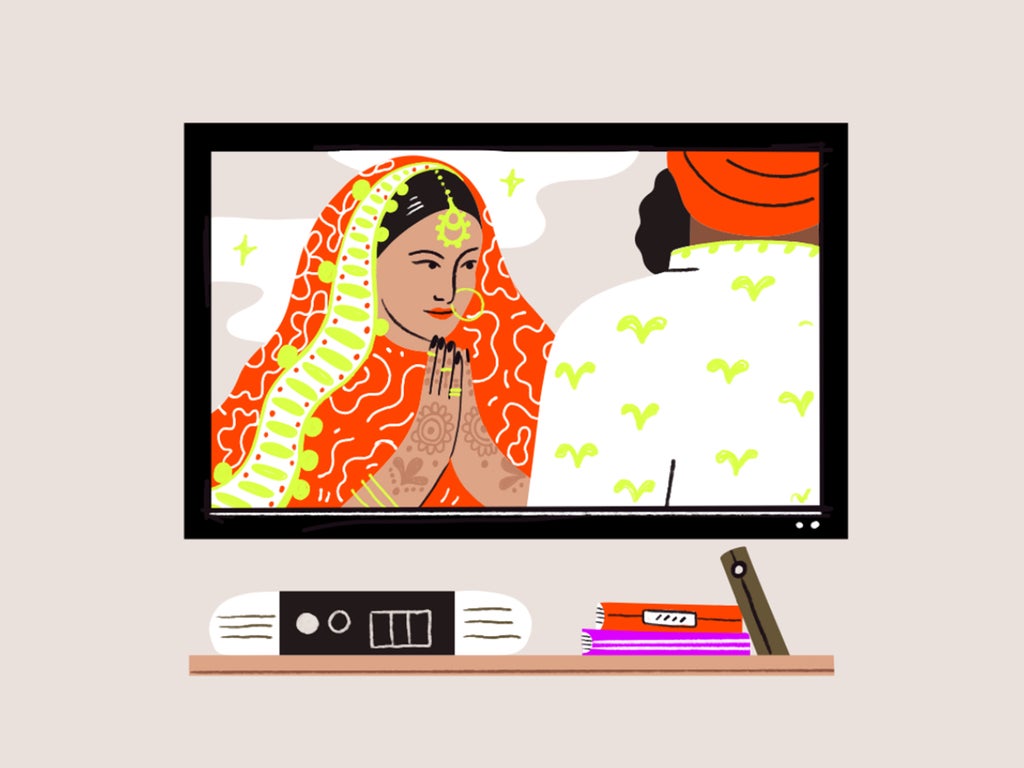

Living in a small remote town in the hills of India means that there is never much to do for entertainment — worse yet, internet connectivity is limited. Despite this, my roommates and I fill our time watching wedding videos, waiting for hours for each of them to buffer to get the full experience. We make sure to pick the fanciest ones; those featuring a beautiful boy are a big crowd-pleaser, and the girl’s clothes and jewellery are essential talking points. We know we definitely fit right into the desi girl stereotype of being enamoured by the Big Fat Indian wedding — right down to the panicked “I’m missing my prime marriageable age!!!” conversations that sometimes follow, filled with the collective fantasies of our own weddings being that grand, beautiful, and happy.

“The groom better cry tears of joy when he sees me in my wedding dress” is one roommate’s prime concern. The other’s worries revolve around finding the perfect, yet affordable wedding lehenga. As for me? Being a queer woman means having a happy wedding surrounded by people I love is almost inconceivable, but that never stops me from dreaming.

When I finally came to terms with my queerness in high school, I started by identifying as bisexual. I wanted to hold on to that tiny sliver of hope that I could still have a “normal” life and get married to a nice man like I was supposed to. My relatives made it abundantly clear what they hoped for me, with remarks like, “You’re going to be the next one in the family to get married. We’ll finally have an excuse for another reunion, can’t wait!” And I wanted that so badly, too. I wanted to give them that reunion. I wanted to sit with all of them and make decorations and gifts, apply Mehendi, and gossip late into the night, like we had at all my uncles’ weddings. I wanted them to celebrate with me, so I tried to convince myself that it would, in fact, happen. All the while knowing the truth: I had very little, if any, interest in men, and it was unlikely that I would spend the rest of my life with one — something I have yet to tell my family.

For the longest time, these thoughts came with a large serving of guilt. Guilt that I was wronging both them and myself — them by taking away their dreams of a blissful reunion, and myself by not correcting their assumptions that I was the next one in line for holy matrimony.

Same-sex marriage is not recognised in my country. While I know that marriage is not the epitome of a relationship, and I’m not even sureI will ever find someone I love enough to marry, it’s a decision I want to make for myself. I don’t want to have it dictated by laws and social norms.

Despite all this, I find myself still making wedding guest lists. I hear myself randomly blurt out things like, “You have to play this song at my wedding” and picking out wedding videographers with my roommates. I plan what food I want to be served and what alcohol my friends would like to drink. I concoct plans of decoy-weddings with my guy friends; then, at least, I can be sure that my family and friends would be happy to come dance with me. In the few moments that I allow myself to be honest about my desires, I find myself dreaming of long-term companionship. But I am quick to rubbish these ideas because I know a big, lavish lesbian wedding in India would probably be the cause of many a heart attack, and perhaps even other types of violent attacks.

That doesn’t mean I still don’t dream of what’s possible. Recently, my best friends from high school and I were discussing weddings on our weekly Zoom call. All three of us identify as queer; one of them was the person who gave me the courage to come out to my class, the first time that I came out to many people all at once. The three of us decided to make a list of all the people we wanted to invite to our weddings. We all shared a common concern: Could we say with any certainty that the people we want at our wedding would themselves like to be there? There were a lot of question marks in front of names on these lists. Would my uncle from Bangalore still want to come to my wedding if he knew I was marrying a woman? What about that grandfather, who is still learning to cope with the fact that women wear shorts in public now? What about my mother? Thinking about my wedding is always bittersweet for me. I imagine the moment when the doors open for the first look of the bride, but worry: What if I step through the door only to be greeted by an empty room?

I like to believe that my mind protects me from myself sometimes by allowing me to dream about perfect weddings but never really picture myself in them. It refuses to let me set up high expectations that would eventually come crashing down. The only kinds of weddings it allowed me to daydream about are weddings with the bride in a white dress, rather than in a red lehenga. At age eight, I had only seen these on TV, and to me, they were the epitome of beautiful “Western” culture, one I so desperately wanted to emulate. (Colonial hangover, anyone?) Even when I grew up, though, I held on to the idea of a white-dress wedding. It was far enough removed from my realities — not only the different dress, but also the concepts of rehearsal dinners instead of Mehendi and Haldi ceremonies and first dances instead of a sangeet — that I could still hope for it. In a foreign land, where two women could legally get married, I would get my chance, too. So when my roommate asks me, “Have you really never thought about your wedding!?” I don’t know how to tell her that yes, I have. A lot. But admitting the kind of wedding that I want feels too much like setting myself up for disappointment.

So, why then does my brain still obsess over the idea of a perfect wedding? My theory is that it’s not actually the wedding; it’s having the people I care so much about care about me and mine. I can point to the day that this fear of not being accepted solidified in my mind. I was a teenager, in grade 10, and my aunt came over to our house. We were talking, and when I told her about Emily’s interest in her girlfriends in the TV show Pretty Little Liars, her instinctive reaction was to laugh and say, “Eww!”

I carry that with me, but I also carry with me the knowledge that I really like this aunt. And I like her daughter, who is eight years old and adorable. I want them at my wedding. I want them to be a part of my family, in the typical Indian-family style, where they want to know the new gossip in my life, like how my marriage is going and when I plan to have children.

I want to imagine a situation where my family is happy for me, wants to get to know my partner-to-be, and wants to support us with their love. I want to blush and laugh when they tease me about my person. But until I learn to live with the vulnerability of voicing these thoughts, however painful they may be, my brain deals by brewing up imaginary but joyful wedding scenarios, holding out hope for that happily ever after.

Welcome to The Single Files. Each instalment of Refinery29’s bi-monthly column features a personal essay that explores the unique joys and challenges of being single right now. Have your own idea you’d like to submit? Email single.files@vice.com.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

My Life As A Single, Lesbian Mum