Recently, when I opened my copy of Kate Zambreno’s 2012 book of criticism Heroines, a feminist rewriting of modernist literary history, I found in its pages a list of symptoms that I had written down in the same kind of black felt-tip pen I still use. I immediately recognised most of them as issues that plagued me during a long relationship: “constant diarrhoea, headaches, rashes, shingles, acne, my left knee.” That last one I don’t remember. What was going on with my left knee? Whatever it was, I felt relieved that it and most of the other ailments had dissipated in the intervening years. The only record of them was there, in Heroines, on page 51.

I wrote that list because it was in those same pages that Zambreno documented the symptoms she experienced while living in different cities because of her husband’s job. Were they real or imagined — who’s to say? I had been listening to Fiona Apple’s “Paper Bag” constantly while I was reading this book, I remember, considering the effects of my ex thinking me hysterical. Women’s art held me up, showing me the universality of this experience: being too much, bursting at the seams, desperate for recognition.

Zambreno is always writing about art intertwined with the self. The embodiment of acts that are generally considered of the mind, like reading and writing, are rendered as vivid and physical as grief, as pregnancy. That’s why I love her work: She is always almost viscerally present in the text, in and of it. In 2017’s Book of Mutter, she writes of the grief of her mother’s death in short paragraphs with the pages unfilled, an enactment of the grasping at lack inherent to the mourning process. Its Appendix Project includes eleven essays and talks she wrote upon Mutter’s release, where she continues to write herself through the reading of others’ work; she expands upon that in 2019’s Screen Tests and, in 2020’s Drifts: A Novel, achieves the notebook feeling of transcribing the process of writing (and makes it utterly compelling).

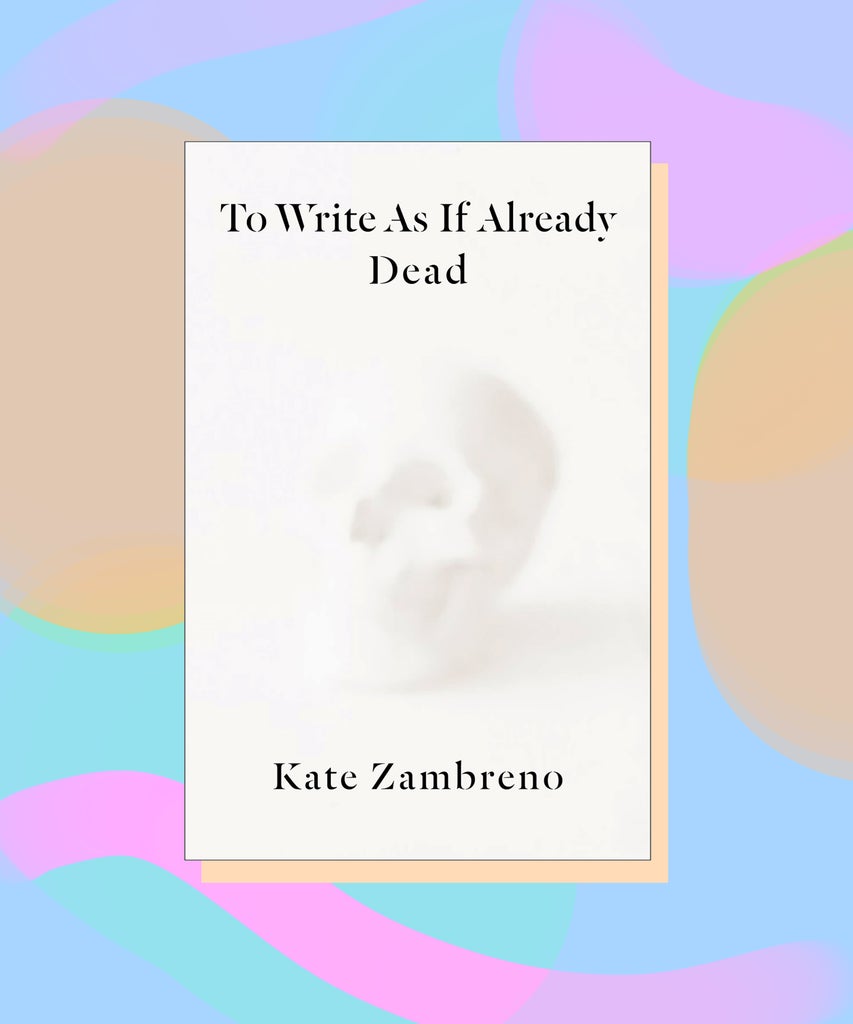

But it’s in her latest, To Write as if Already Dead, in which she ostensibly responds to Hervé Guibert’s To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, that her ability to write the horrors of being a body and a writer in a capitalist world crystallises, becomes sharper. It was mainly written in the pandemic and the second half chronicles the world shutting down, and feeling that the world is also closing in on her is palpable. Guibert wrote of illness and treatment for AIDS, and Zambreno wonders what the significance of first-person writing can be in a world so cruel — when Guibert was writing, and when she is writing now amid the pandemic, describing the unprotected workers who provide for her family while she worries about losing health insurance the week prior to her second baby’s due date.

“The Guibert still feels to me like an essential document, from within (a community, a body). The bodily, adamant, even cruel or hysterical first-person writing of illness fiercely opposes the medical gaze, opposes the absolute anonymity of death. A refusal to disappear. To react against the small moments of coercion, of shaming in the medical process. A document of fear and dread and still beauty—staring at horror, what is its face?”

Zambreno has always been writing from the truth of the body; doing so from even a healthy cisgender woman’s body continues to be a radical act, because our bodies are still always “other.” (This morning I was commiserating with someone about how our periods have changed after vaccination and how no one is really looking into why.) When she is pregnant for the second time, she ceases to have symptoms of illness herself; everything is considered from the central fact that the fetus is most important. She is a vessel.

This connects, for me, to when she is concerned earlier in the text about the “arrogance” of writing and publishing. The condition of the writer relates to the condition of the woman; these are inextricable in Zambreno’s work. “It’s far more of a moral project to be a reader, and not at all to be a writer, or at least an author,” she recounts writing to a friend. Reading cures and writing sickens, but we don’t have one without the other. Writing, like having a body, contains so much embarrassment, so much weakness, so much begging for attention and care. Still, we need it, because we need to read.

The presence of money — the need for it, the lack of it, the work needed to be done to obtain it, the precariousness of it, the anxiety of deadlines missed — also makes Zambreno’s work so essential. Few writers are truly financially successful and stable anymore, which adds to the embarrassment of choosing to do first-person writing in a world that is falling apart. “It is fairly commonplace to want to be a writer or poet,” she writes after reminding us of Kafka’s own day job in insurance. “It is more unusual to stay a writer despite lack of status or outward success, to sacrifice sanity, sleep, positive well-being, health, to instead dwell in a life that is one of almost constant paranoia, oscillating between horror at invisibility and nausea at visibility.”

Thus, To Write as if Already Dead is a book that questions the point of writing, and proves the point that we need writers to explain what the hell is going on inside and outside of them, how these things impact each other, all the jagged edges of being alive and dedicated to thinking about what that means. There’s also the honesty of pettiness that exists in all creative worlds, the points of comparison that are fair and unfair, that gives the text the hiss of gossip that provides instant intimacy. Reading all Zambreno feels like the jolt one gets from a surprise cut or burn in the kitchen, that sudden recognition that you’re in a body and the body can be hurt. That was what she showed me with Heroines, inspiring me to list my maladies. In this new one, I’m reminded again how writing can bring me back into my body. That it’s at its best when it does.

To Write as if Already Dead is available for purchase here.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Unbothered’s Essential Summer Reading List