Much in the way that Karen’s boobs in Mean Girls apparently know when it’s about to rain, I know when a cold snap is about to hit (or if the heating is acting up, or I’m particularly stressed). My toes and the pads of my feet go a numb, yellowish white. More often than not, my fingers do too. This effect ranges from the tips of my fingers and toes being dotted with white splodges while the rest of my digits flame red to, if it’s really intense, covering the whole of my extremities. I lose all sensation in them until I begin to warm up and the numbness is slowly washed away in surges of tingling pain and reddening skin. I may not feel cold anywhere else in my body but my (lack of) blood flow is a reliable warning that a chill – or occasionally, a panic – is here.

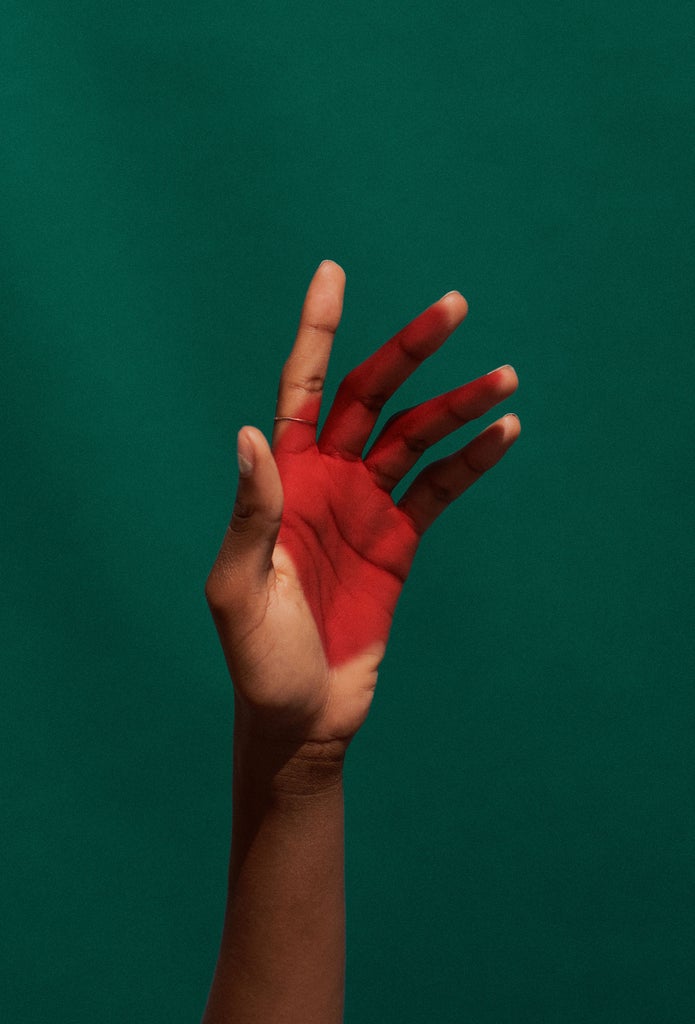

Like many other women under 30, I have Raynaud’s disease. Raynaud’s (pronounced Ray-nodes) means that your small blood vessels in your extremities (such as hands, feet, fingers and toes) are particularly sensitive to temperature change, cold conditions and sometimes emotional stress, and will narrow at the slightest prompt. Everyone’s blood vessels narrow when they’re exposed to cold but the response is far more extreme with Raynaud’s. This results in a noticeable colour change in the affected areas (with skin of all shades going from pale or white to blue and then red as blood flow returns to normal) as well as coldness and numbness, then tingling or pain, especially as circulation returns to the affected areas.

It’s a fairly common condition. According to SRUK, the UK-based charity dedicated to improving the lives of people affected by scleroderma and Raynaud’s, it is thought to affect up to 10 million – or one in six – people in the UK. It’s so common, in fact, that many people don’t even see a doctor about it.

There are two forms of Raynaud’s: primary and secondary. Primary (which is what I have) is the most common and milder form, and can vary in severity. For some it is inconvenient and painful but not debilitating; for others it can seriously inhibit everyday activities like buttoning a shirt, opening a bottle or just handling keys.

Primary Raynaud’s occurs by itself, though what causes it is currently unknown. One theory is that it is hereditary as there are often multiple cases in the same family. What is known is that a Raynaud’s attack can be triggered by changes in temperature, hormones, emotional changes, stress or in some cases by using certain vibrating tools. And while primary Raynaud’s can affect men, women and children of any age, it occurs more commonly in women and often presents before the age of 30.

Dr Emma Blamont, head of research for SRUK, tells R29 that primary Raynaud’s is seen more often in younger women and can in some cases occur at the onset of puberty, with symptoms improving as the woman ages and reaches menopause. Because of this, the theory is that “female sex hormones are potential candidates [for causing Raynaud’s]”. She adds: “There has been some research in this area along with some studies that have implicated a role for oestrogen in cooling-induced constriction of blood vessels.” This has not been proven, however.

As to the link between primary Raynaud’s and stress? “Emotional stress and upset can lead to a Raynaud’s attack,” says Emma, pointing out that the nerves in our body are important in regulating the size of blood vessels and controlling how they dilate or constrict to control blood flow. When these nerves are triggered during times of stress, the blood vessels will constrict, resulting in reduced blood flow to the extremities. “This allows more blood to flow to muscles, which is needed for the body’s ‘fight or flight’ response in response to stress.” This effect can be seen in contrast to other emotional states like embarrassment, where blood vessels in the skin dilate – leading to blushing.

While primary Raynaud’s is rarely life-threatening, it is always painful and frustrating. If you have the condition, it can be worth ruling out any associated conditions that may have caused what is actually secondary Raynaud’s.

Most cases of secondary Raynaud’s (where the overreacting blood vessels are linked to another health condition) are linked to autoimmune diseases which have other, more severe health implications. Scleroderma is one example; other potential causes are rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, lupus, diseases that affect the arteries and carpal tunnel syndrome. Other factors can cause the symptoms, too: most significantly smoking, as this constricts the blood vessels, but also repetitive action or vibration (like playing the piano) and certain medications including those used to treat migraines and ADHD, beta blockers and some chemotherapy agents. However, only 10% of people with Raynaud’s will develop an associated condition.

So what are the ways to deal with it?

There is currently no cure for Raynaud’s. There are some prescription treatments available that can help people with severe or secondary Raynaud’s, such as nifedipine. However these may not be suitable for everyone.

SRUK advises taking a preventative approach that can help you manage your symptoms and minimise the likelihood of ‘attacks’. Some simple things people can do include taking gentle, regular exercise; if you smoke, trying to stop; and getting smart with insulation. For example, wearing a pair of thin cotton or silk gloves under a thicker pair can give added warmth when you’re outside in the cold (ensure you wear insulated gloves when opening your fridge or freezer, too). Another crucial factor is managing stress however you can, as stress can exacerbate symptoms.

We may not be able to control the cold, or our stress response, or our hormone levels. But we can control how many layers we wear. So, my fellow Raynaud’s sufferers, stay warm out there. I’ll be the one in six pairs of gloves until April.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Will Working Out In The Cold Make Me Sick?