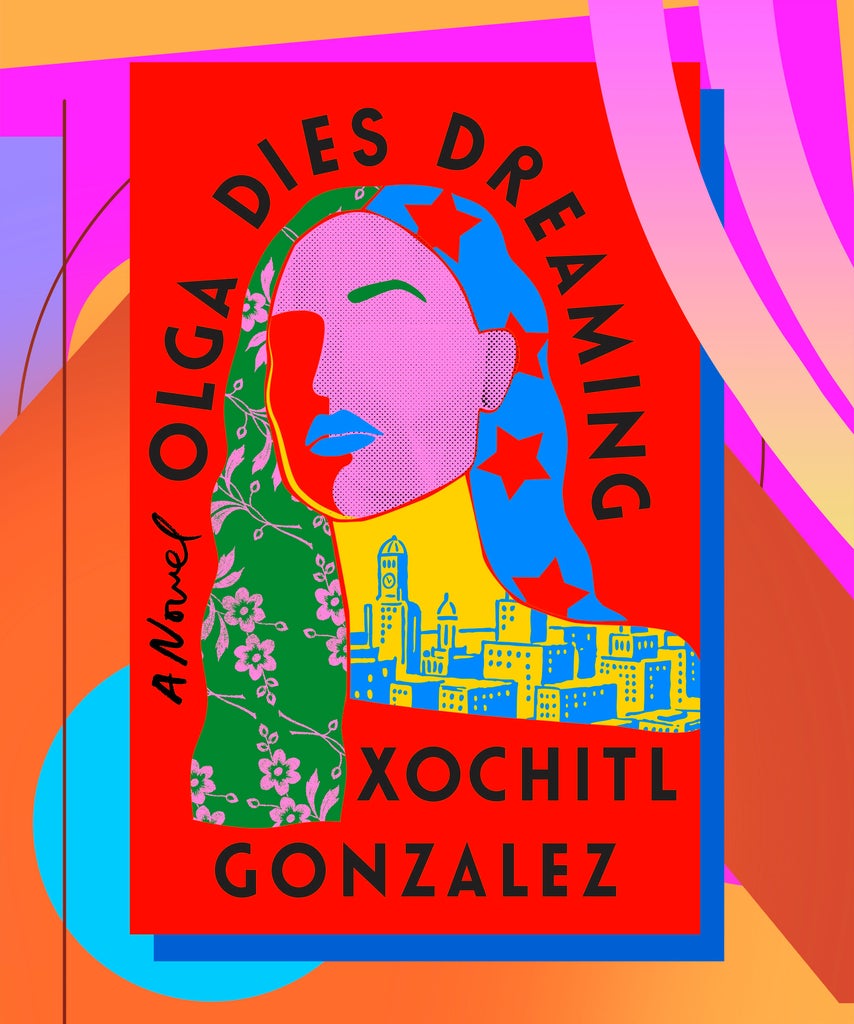

“The telltale sign that you are at the wedding of a rich person is the napkins,” protagonist Olga Acevedo proclaims in the opening line of Olga Dies Dreaming, the debut novel by Xochitl Gonzalez, out this week. As a seasoned wedding planner, Olga would definitely know this detail. Of course, there’s so much more discussed in the novel than napkins, but they — along with Olga’s reasoning for mentioning them — lead us into stories far beyond formal linens.

Olga Dies Dreaming centers Acevedo and her congressman brother Pedro “Prieto,” as they navigate identity and gentrification in the ever-changing Brooklyn neighbourhood they grew up in while dealing with resurfacing familial strife and the fading promise of the American Dream. Set in 2017, months before Hurricane Maria makes its destructive way towards Puerto Rico, the compelling novel reframes the socio-economic and political structures within the U.S and Puerto Rico through their eyes. Gonzalez’ debut speaks thoughtfully to the complicated and introspective diasporic experience, all while looking at how power structures can change a community, and the mixed feelings of pride and guilt that can come along with moving into a gentrified neighbourhood.

For the novel’s release, Gonzalez chatted with Refinery29 Somos about the book (and the pilot for the TV series based on it!), Latinx representation in literature, preservation of community through fiction, and more.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

How are you feeling knowing that Olga Dies Dreaming will be in people’s hands soon?

That’s a big question! Mainly, I’m very excited about the book because I feel like as it’s just starting to go out into the world and people are getting the ARCs [advance reading copies], it’s been beautiful to see some of the early feedback from other Latinas and how it’s hitting home with them. On the other side, I’m a little nervous because it’s a super-personal book and there’s a decent amount rooted in emotional biography and it’s always a little scary putting out there in the world. Writers are kind of reclusive people [laughs]. So far I’m just eager to start a conversation within, specifically the Puerto Rican community and, in general, amongst Latinxs and Latinas, especially, and even if they don’t like it, it’s cool to hear all the different takes on it, you know?

And there’s the pilot too!

The Hulu stuff is also really exciting! I felt like people hadn’t gotten to see a character like Olga or her brother before on a large platform and I wanted it to have the widest audience. Now I’m in this funny position where we’ve taped the pilot, we’ve edited it, and we’ve delivered it to Hulu and we’re waiting for them to make a decision. I wrote it and co-executive produced it with Alfonso Gomez-Rejon, and we just put all of our heart and soul in it as did everybody who worked on it: Aubrey Plaza, Ramón Rodriguez, Jessica Pimentel; the whole cast is just so amazing and now I’m like “I need the world to see it!” It’s just really amazing: we got a very healthy budget and they were very supportive of me not shying away from the politics. That was one of the reasons why I wanted to go with Hulu because some people were like “we make it more of a love story” or “if we make her younger or “if we skip the Puerto Rico stuff,” and I was like no you’re missing the point! Hulu was always like “we want it for what it is.”

I think it’s a challenge for Latinx creators — I didn’t want to write this book or the script where I’m writing for a white gaze. You then have to understand that it’s a risk when you take it to a larger audience because people don’t understand things sometimes, and you have to hope that there’s enough that they’ll go with the flow and that they won’t feel “confused,” [laughs] But I’m so proud of the adaptation. It’s exciting because in the book you can describe a character, you can say “Reggie King is Afro-Latino,” but then when you get to actually see that play out and see the Caribbean Latinx family — I mean most Latinx families — but particularly in Caribbean Latinx families you can have two sisters that look alike except one is an Afro-Latina and one’s not, and I think this is a beautiful opportunity to show the diversity that exists even within our families. The visual of that is so powerful in a way that is an advantage that the book doesn’t have.

It’s great that Hulu took everything for what it is and didn’t want to exclude anything, especially given that the novel covers so much politically.

Oh my gosh, and what a challenge for me because if you think about it, in the very first episode we’re needing to explain to people that don’t even understand, sometimes, the status of Puerto Rico, right? What PROMESA is. And you’re trying to figure out how to do that in an entertaining way, so it was a definite challenge but it was great.

My last living grandparent died a month before my 40th birthday and I don’t know what I was. I always feel like it was her ghost, her spirit, that was like ‘just don’t be afraid to do things.’ I was like: I’m just going to try to write.

What inspired you to write this novel at the time you did and set it that same summer in 2017?

I started writing when I turned 40, and I turned 40 in September 2017. I was raised by my three grandparents, basically. I lived with my maternal grandparents during the year and then I’d spend summers with my paternal grandmother. My last living grandparent died a month before my 40th birthday and I don’t know what I was. I always feel like it was her ghost, her spirit, that was like “just don’t be afraid to do things.” I was like: I’m just going to try to write.

The day after my birthday, Maria hit. I had worked on the Clinton campaign as a high-level volunteer and was pretty disturbed by how few even super liberal Democrats understood the status and the situation down in Puerto Rico, and when I was watching it, I was so pained by what I was seeing and pained that once, you know, the jarring imagery that stopped being trendy on the news and after the paper towels with Trump, it was like nobody gave a shit anymore. So maybe a year later, I began writing fiction and I was writing stories about a middle-aged Nuyorican girl who is kind of self-gentrified, so to speak, and trying to make her way through her own hometown. I realised it was the same character.

There’s a long history of art amongst people of colour being used as a form of protest in some way and a form of calling attention to things and I was like, I don’t want it to be a poetic novel. I want these to be real characters. But I wanted to use the art form of writing to put flesh and bone on why being part of a diaspora has such pull and roots. I felt very strongly that there’s such a tie between the forced diasporic nature of the Puerto Rican people and what’s happening here that’s creating a breaking up of Nuyorican culture because of gentrification. People are being forced out of these neighbourhoods in the Lower East Side, in Spanish Harlem, in Sunset Park because they’re getting priced out, and how that breaks up a community even further and what does that do to the culture. I felt very much like this was a chance to use art to give back, and I just always love books that cover a lot of ground and I thought that this would be a great way to do it.

When you’re starting to write a novel, [you] don’t know that you think you’re going to write another book, or maybe I’m just — if this is the only thing that I write, I want to make sure I talk about all these things! [laughs]. Now, of course, I’m in the midst of a second novel and I’m like okay there’s other books. I had a broad lens of just wanting to put a little stake in the ground about a few experiences that I had felt like I’d seen reflected back to me. It’s that old Toni Morrison quote, right? [“If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.“] That was definitely the main thing I thought of when I was working on this because I was like okay, I haven’t seen these things and so that was a giant motivator.

One of the topics covered in your novel is gentrification, which you also talk about in your newsletter with The Atlantic “Brooklyn, Everywhere.” Why do you feel it’s important to discuss gentrification, particularly through fiction?

Probably it’s because I have a giant amount of guilt [laughs]. I mean, I was generally intrigued and the Atlantic newsletter came up because Jeffrey Goldberg somehow got his hands on Olga and was really into it so we started talking about Brooklyn and he was like “do you want to write about this? You can tell stories about Brooklyn.” I think about first-gen, low-income students, generally, that are kind of buying into this — and I bought into this. I’m not criticising this, I’m just explaining the situation.

We’re told that this American Dream is to do these things, keep trying to accumulate more, and so what ends up happening is that you’re [thinking] I now should live in this neighbourhood because that’s kind of near my friends, it’s near these places that are the cool places to be, and the next thing you know you’re prioritising your career because you want to keep “succeeding.” You can read articles about gentrification and I think, generally speaking, what happens is they become topics. What fiction does is give you this space to show the pain and the conflict around it. You get to experience the emotion of it as it relates to actual individuals in a way that I think is harder to do in non-fiction writing.

So you’re showing the surface level of gentrification but also how it affects communities and people.

Yeah! Let’s say you’re reading an article in The Times or The Washington Post or whatever and there’s a person quoted saying “there never used to be bars here and now that it’s gentrified, suddenly they’re letting bars open” and it hits you, but it rolls off your back. And when you see Olga going back home to her brother’s to hang out and she sees the hipsters going to the market that’s in Sunset Park and then she notices that they started opening bars and it’s all-white bar owners that have suddenly been able to get them. It almost enables you to just embed in the community or in the perspective a little bit more. What’s funny is that I had Olga do what I did, which is that she moved from South Brooklyn to Downtown Brooklyn, but then she herself is watching the neighbourhood that she moved to — which she thought was great — change again, and it’s this feeling that you can get into the headspace of somebody as they feel like they’re being pushed away.

I think that’s why, when done right, fiction is such a beautiful opportunity to help us engage with larger issues and societal issues that sometimes can get flattened.

In a recent edition of your newsletter, you talked about how you wrote Olga in a year and that you felt like you were fighting a clock in order to preserve your version of home through your writing. Can you talk more about that and what your process was like writing the novel?

I just felt like everything was changing so fast in Brooklyn and it still is. I went away to Iowa halfway through writing the book to get my MFA and I came back — obviously, there was the pandemic — once or twice during that time. I saw all the changes that were coming, even to downtown/Fort Greene/Clinton Hill, and I could see already that [area] was getting co-opted and taken over by a very different type of person because of all the high rises and the rezoning and everything else. I just was like I need to write about what this place was and at least anchor it and document it in some crazy way. I also felt that way about Puerto Rico. I just felt this weird race against time in my heart and so I started the book. I was working at Hunter College and I would get up at five every morning and I would work on the book from five to seven and I would get myself to work. On the weekends I wouldn’t do anything before two. I would get up and go to Fort Greene Park when the weather was nice and I’d sit in the park and write the book.

When I got to Iowa, I had like 200 pages, probably, and I went from Brooklyn to Iowa City so there wasn’t that much to do. [laughs] I was so excited at that phase in my life to have the chance to not have to have a job. When I was in college I worked 40 hours a week, so I’ve never had the experience of being in an academic environment without any fiscal responsibility. I was literally there to write, I was like this is paradise! At that point, I was just artistically obsessed. I was so deep into the book that I was just like I need to keep going, I need to keep going, so sometimes I would sleep three to four hours a night because I would just get up and get back to it. I wrote 200 pages from mid-August and I finished the first draft at the end of October. That’s how obsessive I was, and then I worked on revisions.

The shape of the book didn’t change that much if that makes any sense, like what was going to mainly happen. I’m going to quote Toni Morrison again. A thing that comes a little easier to me is plot and construction, but what takes more time and is the real work for me in revision is getting into character honesty. Morrison says that the point of a novel is that most characters are either dealing with some sort of sense of shame or self-loathing and they need to be forced to confront it and they either choose to change or not to change. What I think is the hardest part of writing, for me, is to be brutally honest about what shame or self-loathing each character is dealing with and how do we deal with the confrontation, so a lot of the work that happened in revision was getting deeper and deeper into the truth of each of these characters’ journeys.

In what ways do you feel connected to Olga, especially since there are elements of her life that parallel yours?

We’re pretty connected. A lot of my inspiration for her [came from] when I was 30, I got divorced — she was never married — and my ex-husband was like “you need to go see a therapist” and I was like you’re right! [laughs] I started going to therapy and I thought if I had never gone, what would my 40-year-old self be like without having learned that some of my behaviours were bad coping mechanisms, that there’s a lot of stuff swept under the rug from my childhood. So, I think we have a lot of emotional biography in common. My parents were political activists. I don’t have any siblings but she does. I thought that would be sort of kind to her [laughs].

I wanted to show a single Latina that was not 26. You don’t see a ton of what it’s like to make your way in the world and find love and confront things when you get a little older.

I wanted to show a single Latina that was not 26. You don’t see a ton of what it’s like to make your way in the world and find love and confront things when you get a little older. She’s my uncared-for self finally learning to care for herself. In the show she goes to Brown University, but in the book, I just call it a random fancy college in New England, but I think that experience of feeling isolated and not fitting in and feeling some sense of shame about how you grew up and how you’re perceived and not wanting to feel abandoned, and a lot of these other things were personal things. It’s like the worst ways that they could manifest without ever having some kind of self-examination, and she has terrible coping mechanisms, so in that sense she’s myself had I not taken any care of myself.

What do you hope readers take from reading Olga?

By the way, I was also a wedding planner! [laughs] I should have started there! I was a wedding planner for 13 years and I just thought that was an interesting thing to also have her have.

I really want this book to be more of a celebration of resilience of Puerto Rican people and Nuyorican people. In general though, life will push you down sometimes and we can keep going back up. We’re never quite baked cakes and no one situation has to define us. We can keep going and it’s never too late to find love for ourselves or for somebody else. It’s a book about resilience and love, I think, and finding acceptance. I know it’s got political themes but I mainly think it’s a human spirit book and I think that that sense of resilience is something that we see in the book, in Puerto Rico, in Prieto and Olga, and this idea that I’m not going to buckle. I’m going to keep going.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

R29 Reads: The Books We’re Picking Up This January