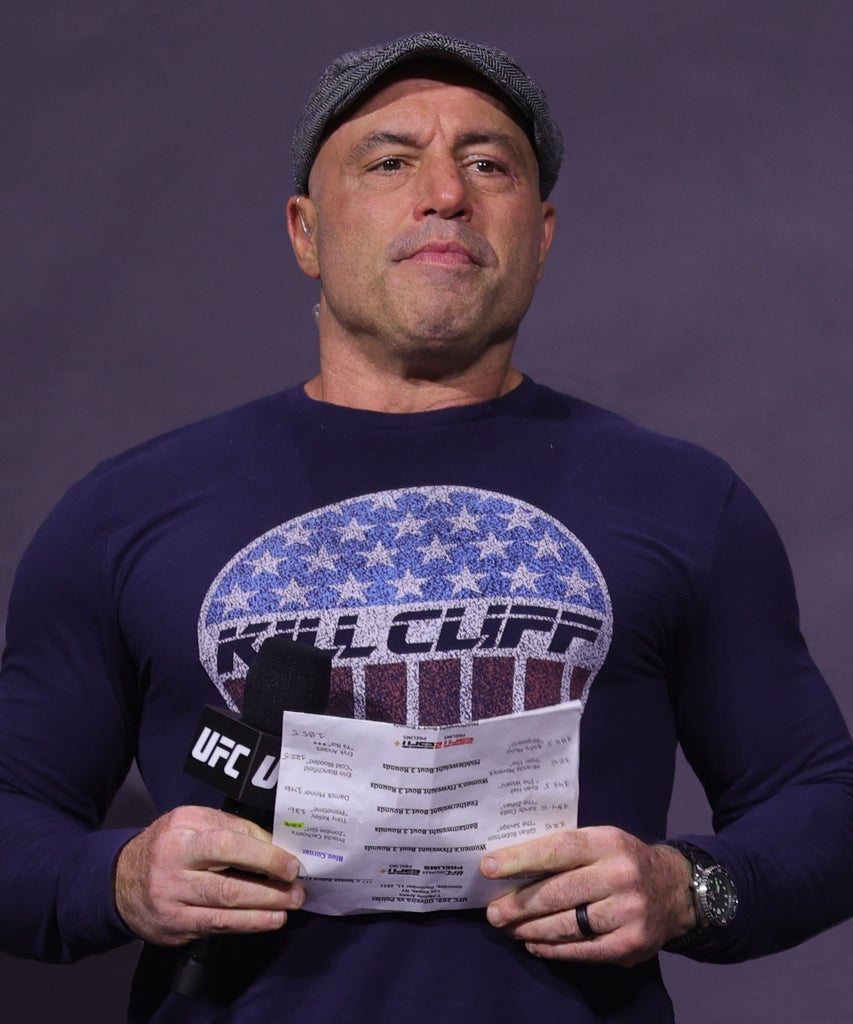

If you’ve made it this far into your life without ever hearing about Joe Rogan, you’re lucky. The longtime UFC commentator, former Fear Factor host, and current host of the Joe Rogan Experience podcast has probably been all over your timeline as of late, and it’s incited a larger debate about platforms and what role they play in hosting misinformation and harmful content.

A recap: Last month, music legend Neil Young asked Spotify to remove his music from its library after accusing the platform of being complicit in spreading COVID misinformation via Rogan’s podcast. (A direct response to an open letter from dozens of doctors and scientists after Rogan interviewed Dr. Robert Malone, who was banned from Twitter for violating the site’s policy on coronavirus misinformation). Soon, stars like Joni Mitchell and Brené Brown followed suit. In the end, Spotify sided with Rogan, and Young’s music was removed. On Sunday, in response to the backlash, Spotify said it would add a “content advisory note” to podcasts that discuss COVID (Which, for the record, apps like Instagram have had in place for over a year). Rogan, for his part, told fans in an Instagram video posted to his social media on Monday that he’d “try harder” to offer balanced information about the virus.

But as many people online have pointed out, the Rogan debacle is only the tip of the content curation iceberg, highlighting a greater issue that Spotify and other platforms that straddle the line between tech and media have around ambiguous platform content rules — and their responsibility to their listeners when it comes to monitoring, and sometimes encouraging, harmful and misogynistic content.

A week before Young issued his ultimatum, Spotify shared on its TikTok account a clip from Off The Record with DJ Akademiks in which influencer and author Brittany Renner confronts Walter Weekes and Myron Gaines — the hosts of Fresh & Fit, a bro dating podcast — for comments made off-camera. She says the pair had warned men to not date women, like her, who they think they’re special (the insinuation being that no woman is) and asks what they get from telling women they’re not. Weekes and Gaines reply that she’s “triggered” and not making any sense (she was making perfect sense). It’s also worth noting the duo has been called out before for racist comments they’ve made about women on their show.

At the heart of this issue — like the Rogan-COVID controversy — is another form of misinformation, or more specifically, notes Bridget Todd, the host of iHeart Podcast’s There Are No Girls on the Internet, misinformation of identity. “Misinformers really traffic in lies about who we are, lies about our identity,” she tells Refinery29. And women of colour and Black women are disproportionately impacted by this. “Sometimes being a Black woman podcaster feels like being in a racist, misogynist swamp.”

And it’s not just a Spotify, or Fresh & Fit-specific problem. Quickly scan Apple’s top 20 podcasts of 2021, and you’ll find, alongside Rogan, The Ben Shapiro Show (hosted by conservative commentator Ben Shapiro, who’s probably most infamously known for tweeting that women who get wet need medical attention). Also hosted on the app are The Dan Bongino Show by Dan Bongino, another conservative commentator who was recently banned from YouTube for COVID misinformation, as well as Jordan Peterson’s The Jordan B. Peterson Podcast. Peterson has been in the news for sexist and stereotypical comments about genders, endorsing “enforced monogamy,” and refusing to use people’s preferred pronouns. “And yet, there [Bongino] is [at] number six on the Apple podcast charts,” Todd says. Bongino, Shapiro, and other similar podcasts are also available to stream on platforms like iHeart and Amazon Music.

Rogan aside, there are plenty of other individuals who have a wide platform to share problematic and harmful ideas. Platforms say they are addressing the issue. Spotify has a policy around “dangerous content,” saying creators should avoid “content that targets an individual or identifiable group for harassment or related abuse” as well as any “content that incites violence or hatred towards a group of people based on race, religion, gender identity or expression, [and] sex,” among other factors. Under the latter, the policy says creators must avoid “dehumanising statements about a person or group” based on the characteristics above. (Spotify notes that the examples are “for illustrative purposes and are not exhaustive”). Apple has its own set of content guidelines as well, which outline “Illegal, Harmful or Objectionable Content,” and note that podcasts which contain harmful or objectionable content that’s disputed by an authoritative source may be labelled to reflect that. But that’s about as clear as it gets. There are no guidelines on how exactly violations of these policies are measured or how the platform implements them. Spotify could not be reached for comment, and Apple declined to comment for this story.

As Stacy Lee Kong, the founder of pop culture media brand and newsletter Friday Things, tells Refinery29, making public these policies that have reportedly been in place on the back end doesn’t address why this type of content remains up on the platform, or at least doesn’t have some sort of trigger warning.

Sometimes being a Black woman podcaster feels like being in a racist, misogynist swamp.

Bridget Todd

This isn’t a new conversation. In many ways, it’s one that companies and consumers have been having for years, first with Facebook and Twitter around the company’s rights and limitations to censoring harmful content and misinformation, such as with the 2016 presidential election, and more recently last year with streaming services like Netflix, which received complaints about Dave Chappelle’s transphobic comments in his comedy special.

But Spotify’s decision to continue hosting harmful content says a lot about it. As Lee Kong wrote about the controversy around Fresh & Fit: “Spotify is choosing to specifically prop up media that targets impressionable young men and gradually inducts them into a culture of misogyny, hate and selfishness, something made easier by the very nature of podcasts and how people tend to hear about them.”

Spotify CEO Daniel Ek said in a statement that a streaming service doesn’t take on a position of content censor. But that frankly just doesn’t cut it, especially when, as Todd notes, it’s good business for them not to. “Spotify invited Joe Rogan knowing the kind of content that he creates onto their platform, and they pay him $100 million dollars a year to make that content,” she says. “So them acting like they’re just a neutral platform who can’t exercise any kind of control or editorial standards for the content that they pay for doesn’t really hold water. … They’re a publisher, and it shouldn’t be controversial for a publisher to exercise a little bit of editorial decision making and fact checking and things like that.”

For Lee Kong, the issue is that Spotify is trying to have their cake and eat it too. “I think what their problem is that they’re trying to have it both ways,” she tells Refinery29. “They want to financially benefit from having these companies on their platform, so they pay for it… But now they want to say that they’re just posting content like they don’t have any editorial oversight.”

To be fair, there’s a bigger challenge when it comes to monitoring podcasts that aren’t explicitly produced or made by the platform it’s hosted on. Some podcasts are licensed to specific streaming platforms and others can be made by regular people like you and me and submitted to Apple through a hosting provider. (For example, while Shapiro’s show is available to listen to on platforms like Apple and Spotify, it’s created and produced by The Daily Wire). And in many instances, unlike when someone is removed from a social platform like Twitter or Facebook, podcasts removed off services like Apple can still be re-uploaded via an RSS feed (it’s kind of complicated, but essentially, if listeners want to find a podcast that’s been removed from the platform it was hosted on, they can).

Platforms are in a tricky spot; but regardless of these limitations, Todd believes they still have a duty to try and monitor these potential harms. “I do think that these platforms have a responsibility to try,” Todd says. “We need to get to a place where we don’t just accept that our digital media landscape is made up of people who are scammers and liars and people who traffic in things like racism and misogyny. I refuse to accept that that has to be the standard.”

In a recent piece for The New York Times, writer Roxane Gay explained why she also chose to remove her podcast from Spotify in light of the Rogan debacle: “There’s a difference between censorship and curation.” Freedom of speech doesn’t mean you can say whatever you want, without consequences, Gay writes. “When we say, as a society, that bigotry and misinformation are unacceptable, and that people who espouse those ideas don’t deserve access to significant platforms, that’s curation,” Gay writes. “We are expressing our taste and moral discernment, and saying what we find acceptable and what we do not.”

Given our current media landscape, which is fuelled by a draw to extreme takes and opinions, outrageous and divisive comments are what garner views and listens. Views that then turn into clicks and shares and ultimately, money for these platforms.

Unlike COVID misinformation, content promoting misogyny and transphobia is more problematic because it’s more difficult to identify and outright call out as incorrect. But these issues are also ingrained in our society, which may be, in part, what makes them so easy to overlook. “When Joe Rogan gets on a podcast and discourages young people from taking the vaccine or other things that are clearly not true, it’s very easy to have public health professionals say it’s not true,” Todd says. “It’s a little bit more difficult when people traffic in lies and misinformation about our identities.” It’s easier to dismiss claims of misogyny, racism, and transphobia, when these issues don’t affect you, Lee Kong adds.

While it may feel insurmountable, the power to elicit some sort of change still lies in the listeners’ hands. Todd advises media consumers to ignore the urge to share or engage with the content directly, even if it’s to retweet about how hurtful or terrible said content is. “I know that when I do that, because of the nature of the algorithm, I’m actually only making it more powerful, and it’s a spread,” she says. Instead, when you see something on your made-for-you page that’s untrue or harmful, report it; then focus on sharing info that’s factual and will counterbalance it. “It’s really important that everybody understands that individually, when you’re scrolling your feeds, you can make choices that help make the media ecosystem a little better.”

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Thank Jewel Ham For Our Spotify Wrapped Obsession