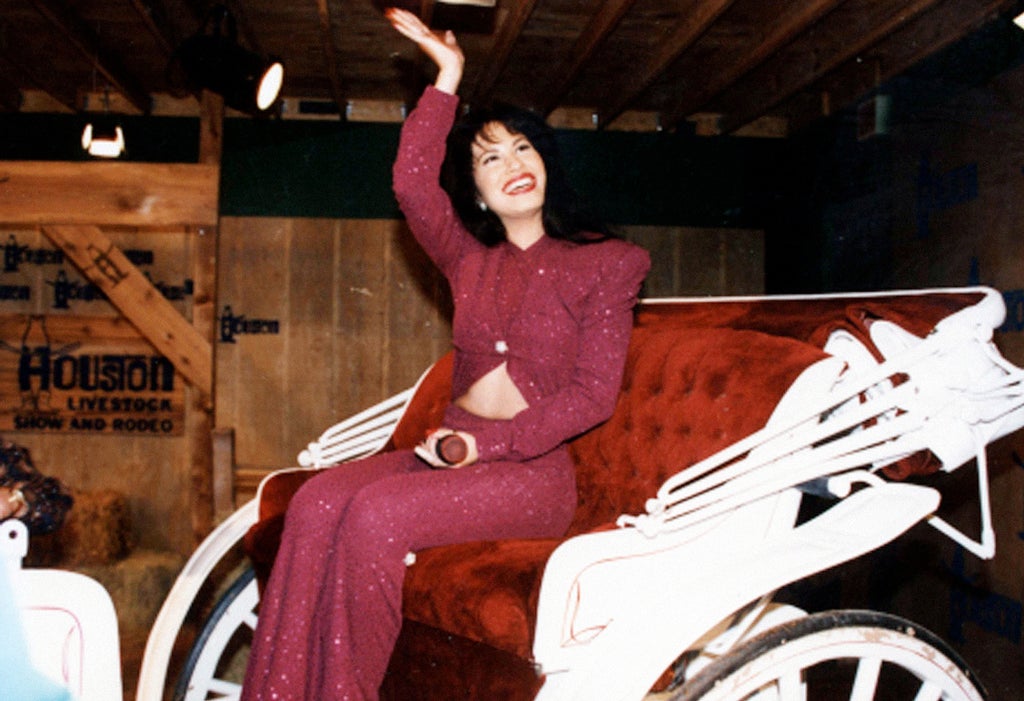

Twenty-seven years after her untimely death, Selena Quintanilla-Pérez is still a hard act to follow. She is undisputedly the queen of Tejano music and is recognised as one of the greatest, most influential Latinx artists of all time — and no one benefits from this more than her nuclear family.

Not long after the late singer’s murder on 31st March, 1995, the zombification of Selena commenced: Selena films, albums, dolls, clothes, makeup, and more were available in stores and, later, online. Abraham Quintanilla, the entertainer’s father, has long been accused of profiting off his dead daughter and exploiting her story ad nauseam through his company Q Productions. The production house was behind the 1997 biopic Selena, which grossed more than $35 million and has been rereleased this month in celebration of its 25th anniversary. In 2020 and 2021, viewers saw a near-exact retelling of her biography in Netflix’s Selena the Series, which was co-produced by the family. There’s also a Selena MAC Cosmetics collection and a Forever 21 apparel collaboration with the Quintanillas, a family-run Selena museum and festival, Fiesta de la Flor, and a now-cancelled Selena hologram tour.

More recently, when Quintanilla announced in March that a new posthumous Selena album was in the works, to be released this month, it was received with an outpouring of mixed emotions — especially given that it comes with an A.I.-dystopian-leaning peculiarity: It will feature the singer’s digitally altered voice. According to Quintanilla, Selena “sounds … like she did right before she passed away” on the project, which includes arrangements by Selena’s brother A.B. and artwork by sister Suzette. While some expressed their excitement about the possibility of unreleased new music, many were quick to point to the conspicuous exploitation of the beloved singer. “This is sickening. Abraham Quintanilla should let his daughter rest in peace,” one user wrote on Twitter. Another one added, “The Quintanilla family be really doing everything to keep getting money.” Refinery29 Somos reached out to Quintanilla for comment but has not heard back. However, during an interview on The AC Cruz Podcast in 2021, Quintanilla addressed accusations about the after-death exploitation of Selena by referring to critics as “dogs.” “I say so what, let them talk. Dogs get old from barking. Let them bark all they want to,” he said.

Still, none of this is new. “Institutions have long capitalised on — and I mean literally generated capital from — Selena’s music and memorialisation. These institutions include the recording industry, cosmetics industry, Hollywood, and, yes, even the family itself,” Dr. Deborah Paredez, a poet, professor of creative writing and ethnic studies at Columbia University, and the author of Selenidad: Selena, Latinos, and the Performance of Memory, tells Somos. “As I learned in my research and have observed in the years since, these ‘official’ memorials constitute only one small part of the complex and vast landscape of Selena’s enduring legacy.”

“Institutions have long capitalised on — and I mean literally generated capital from — Selena’s music and memorialisation.”

Except, Quintanilla does not want anyone else cashing in on Selena. In fact, Selena’s father has threatened several small artists that have used the singer’s songs or image with legal action. One cease-and-desist letter handed to an indie performer states, “Q Productions is the sole and exclusive owner of all rights in and to the name, image, and likeness of the artist Selena Quintanilla-Pérez (‘Selena’).” Even the singer’s widower, Chris Pérez, who was legally first in line to inherit Selena’s properties as husband, was quickly stripped away from it all. In an interview with Rolling Stone, Pérez disclosed that during a time of grief, and after Quintanilla’s insistence, he entrusted his father-in-law to make all arrangements since Selena left no will. Now, the Quintanillas hold exclusive ownership of Selena.

For decades, the family has used this absolute power to package and resell the same images of Selena — and some believe the spirit of the adored performer and cultural icon is removed more and more each time. “If we are making copies of a copy of a copy, humanity gets lost, the skin tone gets lost, the body gets lost,” writer and critic Alex Zaragoza tells Somos. “All these things get lost because the family has very tight control of her image and makes money off her to the point where they send cease-and-desist letters to artists.”

According to Zaragoza, a fellow border-lander and Selena fan, the zombification of Selena is, well, unnerving. “If there were unreleased demos, or music that never got out, OK, there’s music. But you think at this point, after [27] years, they have squeezed out every single possible demo to digitise and piece together her voice to create new things. Honestly, it feels gross,” she says.

There’s no denying, though, how much Selena and her family meant to each other. As immigrants and first-, second-, or third-generation Latinxs, we understand too well what we’re willing to do with and for family. For instance, I myself, the daughter of immigrants and fronteriza, grew up travelling back and forth on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border as my parents vended at swap meets across San Diego, Tijuana, and Ensenada. Privileged white-American onlookers might claim “child labour” because my parents enlisted me, at six years old, to draw customers into their booth and later, as a teen, to sell second-hand items for them at my own booth, but I was happy to help generate funds for my family. Like me, it’s easy to assume Selena was, too.

“One thing to keep in mind is that Selena’s voice became the tools for her family’s survival. She was singing and performing at nine years old to put food on the table,” María García, journalist and creator and host of the award-winning podcast Anything for Selena, tells Somos. “One thing I learned about Selena was that that was deeply meaningful for her. She was completely fuelled by the idea of helping her family advance in life. And that is the inherent tension.”

Still, Selena’s family is not struggling financially anymore, and it has rubbed some audiences the wrong way that the Quintanillas have been extremely adamant about barcoding any kind of “other” Selena representation that doesn’t derive from them. And the waters get murkier considering all that’s been done under her name since her murder.

“I think it’s complicated,” García says. “When Selena died, Mr. Quintanilla said that he was going to make it his life’s mission to make sure that the world never forgets about his daughter. And he has kept that promise, maybe not in the way that some of Selena’s fans agree with, and maybe in a way that has unsettled people, but it’s sort of his life’s mission to keep her memory alive.”

But whose memory of Selena is he keeping alive? Selena was only 23 years old when she passed away, a young adult entering into womanhood and finding her autonomy. “She didn’t even get to the point where she was fully reflecting on what happened to her and the life she led. That story is told by her dad, brother, sister, and mom the way they believe is right, and molding it into the way that benefits them the most,” Zaragoza points out. “Let’s say I died, if my parents said, ‘Hey, let’s take all of Alex’s stupid blogs and sell merch’ without ever thinking what I would want, I’d be haunting their houses.”

As for García, she doesn’t believe anyone could know whether Selena would be honoured or appalled by the stewardship of her legacy. Still, through her podcast, the journalist presents a different memory of Selena. Unlike the same retelling of Selena’s story via Q Productions — good girl who listens to her family except that one time and gets murdered by the president of her fan club — García’s project highlights the riveting facets that “Selenidad,” a term coined by Paredez to describe the cultural phenomenon based on the collective grievance of Selena’s passing, brought to the fore. Spanning topics like whiteness and colourism, body politics, Tejano tensions, and Spanglish, García offers deeper dimensions, not just about the fallen superstar, but Selena as a symbol of hope, resistance, and solidarity. But García needed approval from Quintanilla to make her podcast possible, which took her many attempts. Without it, there would not have been Anything for Selena, or, consequently, a fresh public discourse on Selena’s life, music, and legacy.

As a scholar and fan, Paredez is more interested in these “unofficial” acts of Selena commemoration than official ones like the forthcoming posthumous album. “I am curious to see how Latinxs and other communities who make up Selena’s fan base will respond to or engage with these official memorials in ways that may comment upon or intervene in the very commodification of Selena,” she says. “These unofficial acts of Selenidad have often restored my faith in our capacity to endure in a culture that regularly profits from appropriating the labour and creativity of women of colour.”

In her book Selenidad, Paredez writes that remembering Selena through performance and memorialisation in the ‘90s and 2000s became a way for our communities to understand our own identity as Latinxs, art makers, U.S. citizens, and immigrants in an era when our stories weren’t represented or shown in a positive light in mainstream media. Paredez explains that Selenidad also helped pave the way for the so-called “Latin explosion” of that time while putting Latinxs “on the map” and “on the market” to commodify.

“Instead of just continuously finding ways to profit off Selena, why not use her memory and her important place within the culture to spearhead, nurture, and foster the next generation?”

“While Selena’s tragedy offered a way for many Latina/o communities to mourn their own plights resulting from political economic struggles throughout the 1990s, numerous corporate and political forces deployed Selena’s tragedy as a way to construct Latinos as hot commodities and valued consumers while denying their status as citizens,” Paredez writes in her book. She also explains that Selena’s tragedy came at a time when political tensions concerning the Latinx population were at play, such as anti-immigrant policies, the labour oppression of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and femicides on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Little has changed. In the year 2022, at a time when Latinx migrants continue to be sent away and/or abused at the border, detained and deported, and criminalised for their intent to survive, we are still deprived of other stories — tales beyond our plight and beyond Selena. “It gets exhausting,” Zaragoza says. “Why not branch out?”

To be clear: This isn’t to say that we shouldn’t continue celebrating Selena’s enduring legacy. In fact, it was apt for her to be honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2021 GRAMMYs. This also isn’t a call for the Quintanillas to stop producing materials pertaining to the Selena branding. But instead of a zombified Selena album, maybe the über-talented family of musicians, producers, and managers can focus their attention on discovering and cultivating more talent aligned with the vision, ideals, and philosophy of Selena, La Reina.

“They could’ve established a pipeline by creating an organisation for young women coming up in Tejano music, where they could offer musical support and connect them with people,” Zaragoza says. “Instead of just continuously finding ways to profit off [Selena], why not use her memory and her important place within the culture to spearhead, nurture, and foster the next generation? Imagine how many artists they could have discovered and how many new Selenas they could have brought and introduced to the world.”

Another idea: establishing a fund for victims of gun violence. “She literally died as a victim of gun violence. These are all things that could honor her instead of just cashing in on her,” Zaragoza continues. “But now this album? It just seems nonstop.”

Selena’s importance to fans, Latinx culture, and our communities is undeniable, and so was (and is) the Quintanilla family’s love for each other. But when a shooting star has risen so high and traveled so far after death, their everlasting mystique belongs to the world of fans and artists to explore and celebrate — at least it should.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?