Democrat-blue balloons and bawling women — that’s what El Sanchez thought of immediately when they first learned of the U.S. Supreme Court draft opinion that will likely overturn Roe v. Wade (the 1973 landmark decision that legalised abortion in the U.S.). It took them back to election night in 2016, when they attended a party in their home state, Washington. As it became clear that then-presidential candidate Donald Trump would hold the highest office in the land, Sanchez saw women sobbing in the corner of a bar, surrounded by cobalt-coloured decor and flowers. They’d thought then-Presidential Candidate Hillary Clinton was a shoo-in. When Sanchez went to check on them, “one of the girls screamed at the top of their lungs, ‘They’re coming for us! They’re coming for us. They’re coming for our rights,’” Sanchez recalls. “I remember thinking, I hope I won’t remember this moment.”

Almost six years later, they can’t help but feel that the two women were correct.

Although Trump is just one factor in a long history of people and institutions chipping away at reproductive freedom, the state of abortion and human rights in the U.S. feels increasingly bleak. The leaked draft opinion, as it’s written, could also have Fourteenth Amendment implications beyond abortion, and be catastrophic for potential rulings on LGBTQ+ marriage and birth control. Suffice to say, Sanchez is concerned for the future — and that, as a nonbinary person, they could be left out of a movement often spear-headed by white feminists in pink pussy hats as the fight against these injustices continues.

Many Americans have complicated feelings about abortion and the battle for reproductive access, in part because of stigma that’s perpetuated, experts say. But there are many folks who know exactly how they feel about abortion, seeing it as a life-changing and even life-saving event. They know because they’ve had them or fought like hell so others could or both. We spoke to five such people about how abortion access changed their lives, how we got to this moment, and all of the feelings — yes, both complicated and not — that they have about abortion.

My Abortion Story: Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez, 37, Nashville, TN

Prisca Dorcas Mojica Rodríguez discovered she was pregnant right after deciding to leave her husband of four years. “I had just packed up everything and moved into a new place, and was starting to figure out what it was going to look like to be single,” says Mojica Rodríguez, who was also in the middle of graduate school at Vanderbilt and knew she’d have to drop out and move home with family if she had a child. “I was very confused by the pregnancy because, you know, women are socialised to want kids, but sometimes we have to figure out what we really want — despite all the messaging.” She chose to have an abortion.

When making the decision, Mojica Rodríguez also grappled with familial expectations. She was the daughter of a pastor and grew up in a conservative household — in Nicaragua until she was seven years old and then in Miami, FL. She married young, at 23, because that was what was expected. She also had an adopted sister who factored into her early ideas about abortion. Her sister’s birth mother tried to induce an abortion illegally in Nicaragua, but ended up in the hospital and decided to put up her baby for adoption instead of admitting to her parents that she had been pregnant. “My mom always said, women regret that decision,” Mojica Rodríguez remembers. “So, [when I had my abortion] I wanted to make sure that I was feeling everything and could sense if there was regret so that I could even just process that if I had to. But, I never — I felt relief. I remember leaving the clinic and it just felt like a huge weight was off my shoulders. Because there was so much at stake if I kept that pregnancy.”

Years later, as she was starting out her career as a writer, she found out she was pregnant again and had another abortion. “[My partner and I] talked more seriously about it because I did know I wanted to be with this person, but I also was really invested in what was happening in my career,” she says. ”We don’t acknowledge how much invisible labor women do when they’re mothers. As much as I had someone who was really supportive, I knew that it was going to be really hard, and I didn’t want to add that to my life.” Three years later, she landed her first book deal. Now, she’s the author of For Brown Girls with Sharp Edges and Tender Hearts. She credits this, in part, to “that decision to focus on myself — which was very much my feminist practice that I wasn’t taught but that I definitely claimed.”

Today, abortion access is a cause Mojica Rodríguez cares deeply about, and she uses her writing to fight abortion stigma and the idea that people always regret abortions. When it comes to abortion, “some people need it and some people want it,” she says. “It isn’t just this immediate regret. Sometimes we carry other people’s regret. I used to think, Maybe I’ll regret it later if I’m 40 and I never have kids. But I’m almost 40 and I’m still at this place of like, No. That was the best decision I could have made at that time in my life because I wouldn’t be where I am today without that decision.”

My Abortion Story: Angela Fremont, 71, New York, NY

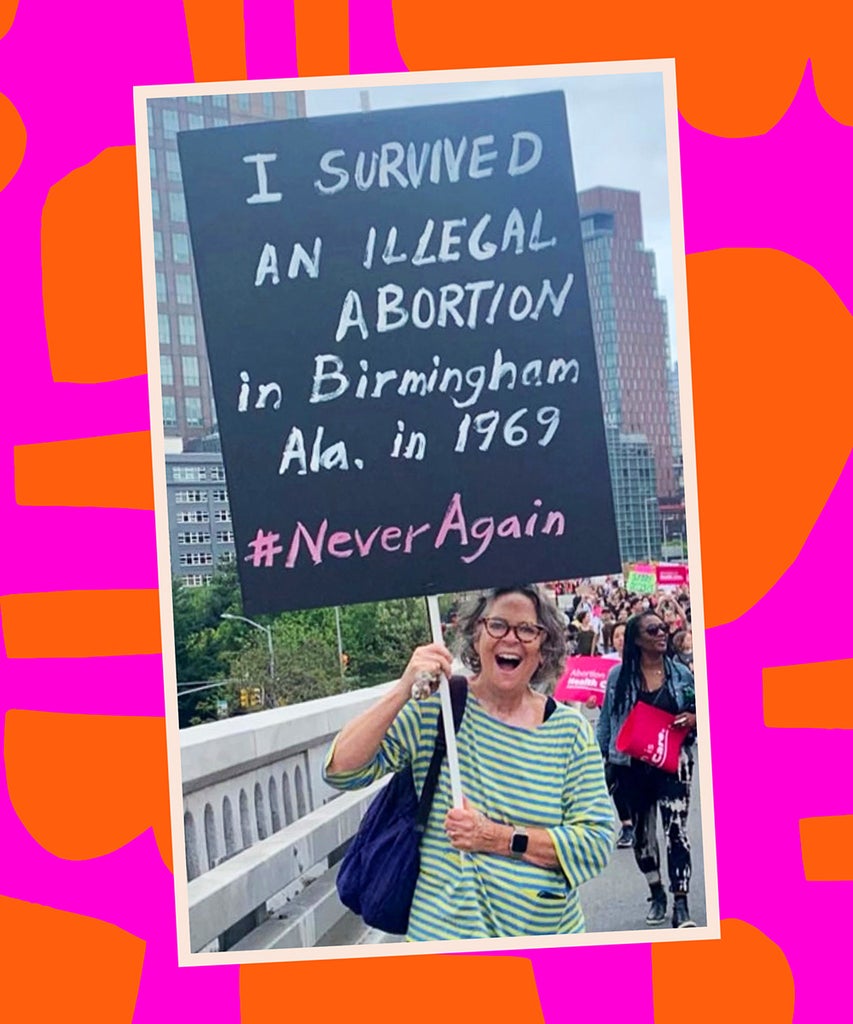

For months, Angela Fremont has been showing up to any reproductive rights rally she can find holding a large black and pink sign that says, “I survived an illegal abortion in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1969. #NeverAgain.” It prompts a lot of attention. At the movement at Foley Square in New York, the day after the Supreme Court draft opinion came out, many young people came up to her and thanked her for telling her story — some also sharing their own abortion experiences. One young woman even began to cry, and Fremont hugged her close with one arm, the other continuing to bolster her message and the sign.

It’s moments like these that make Fremont glad she can share her story — though she believes she never should have had to have the experience she did. “The reason I’m showing up and speaking out is because: People need to know that women are gonna have abortions,” she says. “They have always had abortions. And the question is, are they going to have safe abortions?” Although most experts agree that we’re a far cry from going back to the level of unsafety that existed before 1973 — thanks to advancements like medication abortion pills and more widespread information about options and resources available — banning abortion will make the environment less safe for pregnant people.

“I’m worried about women showing up in hospitals in the condition that I was in in 1969, hemorrhaging with a fever, septic, on the verge of death,” she says. At the time, she was 18 and living in Miami, FL. The first doctor she went to asked “if I was married, and when I said I wasn’t, he called me a whore and told me to leave his office,” Fremont recalls. The second doctor said he couldn’t help, but suggested she go to Puerto Rico, which was too expensive. She tracked down a less-expensive option in Alabama, where the doctor told her — while half-watching the Mets play on the TV in his office — that she was too far along for him to help. He did, however, recommend someone who could.

She found herself driving down a dirt road, to a filthy shack where there were three dogs locked up inside “a room with a bare lightbulb hanging over two sawhorses with a sheet of plywood,” she recalls. “[The person doing the abortion] explained that she was going to put a hose through my cervix into my uterus and that I was to keep the hose in there for 24 to 36 hours.” Fremont flew to Tallahassee to convalesce with friends who helped to pay for the abortion, but they became so concerned about her rising fever that they dropped her off outside a hospital. After being aggressively questioned by police, she learned she couldn’t be admitted because she was underage and had to have another friend pose as her mother on the phone. She was finally admitted and they gave her a D&C. “I survived,” Fremont says. “And I was one of the lucky ones.”

Having her abortion enabled Fremont to become the person she is today. Now, she’s a married mother of two, an artist, a teacher, and a person using their experiences and platform to push for change.

My Abortion Story: Ebony Wiggins, 30, Nashville, TN

It was a freezing winter day when a 22-year-old Ebony Wiggins showed up at a Planned Parenthood in her PJs. That morning, she’d taken a home pregnancy test and immediately called her OB/GYN when it came back positive. They’d referred her to the clinic. She headed there in a rush, not even brushing her teeth or hair before leaving the house. She was able to have a medication abortion right away, as this was before her state implemented a 48-hour mandatory waiting period. She feels lucky she didn’t have to undergo the compulsory, biased counselling that’s now required. Still, she would have gone through with her decision regardless — and no matter the hurdles, she says.

She now works for Planned Parenthood full time, advocating for those who have even less access than she did. “I’m insanely grateful for my abortion — if I didn’t have access to it, I could have an eight-year-old at the moment and my life would be totally different,” Wiggins notes. ”I wouldn’t be able to do the work I’m doing now, and I wouldn’t have had the time and space to become the person I’m developing into.” Those are some big reasons abortion changed her life for the better, but there are also little reasons she’s thankful for her abortion, too. “I can come home and decide what it is I want to do,” she says. “I can watch Real Housewives, be able to play music, and not have to worry about a small child. That’s a big difference from what my life would have been like. And, it’s allowed me to think more about the mother I would like to be if and when I decide to be one. For me, once I’m a mother, it won’t be about me anymore.”

It’s clear she’s definitely operating with others in mind in her work now. She condemns the Dobbs v. Jackson’s Women’s Health Organization draft opinion that seems like it will overturn Roe, and other laws and rhetoric contributing to abortion stigma. “Nobody should feel ashamed for having an abortion,” Wiggins says. “There’s absolutely nothing wrong with it and their decision to have it is totally their own.”

My Abortion Story: El Sanchez, 39, Olympia, WA

El Sanchez believes that all people should be able to access abortions — and as many as they need. They’ve had two. Their first was in their mid-20s when they identified as a woman. Their second occurred six years later, after coming out as nonbinary, when complications with contraception left them pregnant again. When you have a second abortion, “all of a sudden, you’re this horrible person,” they say. The first time, feminist friends who owned IUD-shaped earrings were rallying around them, but, the next, they felt largely abandoned and judged, they say.

It wasn’t just friends and loved ones who didn’t seem to get it. The medical side of the experience was much more isolating, too. During the first procedure, “I made the doctor laugh and she gave me flowers and she called me the funniest abortion she ever performed,” says Sanchez, who’s a stand-up comedian. The second time, though, “the staff misgendered me the whole time. I kept correcting them in the middle of the procedure… I ended up just laying there and crying about how unseen I felt.”

For Sanchez, the experience also brought up feelings of internalised shame. “As a Mexican, Indigenous person who’s mixed race… I’ve lived in some primarily white places, and there was just this idea of kind of [having to] fight the stereotype that you’re trash,” they say. “Especially with the stereotypes people have about Latinx people having a lot of kids… There’s that fear: What will people think if I’ve had multiple abortions?”

Although they’re still processing internalised shame and other feelings about their abortions, “I still think it was the right thing,” they say. “I needed those years to grow as a person and I couldn’t have done that while trying to raise another person.” They add they wouldn’t have been able to start their career either. “I also think I would have been stuck in a cycle of generational poverty if I had had kids early,” they say.

Sanchez has a child now who’s four. “I think if I hadn’t felt so shitty after my second abortion — it absolutely was the reason I decided to keep my current child,” they say “It’s hard to say it because now I know my kid as a person — a person I love… I’m a better parent now because of the first two [abortions] I had, but I would have been an even better one if I had decided maybe not to carry my last pregnancy to term.” They say it’s a complicated feeling and a difficult hypothetical to even consider because they love their child and would do anything for them. But, in the end, they say shouldn’t have had to experience such shame over the idea of having a third abortion — or a second. Or any number at all, really. “But it’s hard when it’s pushed on you,” they say of the stigma around abortion. “It’s so unfair.”

The way they see it: “If you’re pro-choice you should be pro-every-choice-someone-has-to-make.”

My Abortion Story: Valerie Peterson, 43, Las Vegas, NV

Valerie Peterson was 17 when she had her first child. She was raising her daughter while going to college and working full-time when she discovered she was pregnant again. She decided to have an abortion in order to give her daughter the best care possible while pursuing her dream of becoming a university graduate — a goal she achieved by graduating from Northern Illinois University in four years and later going on to get her master’s and doctoral degrees.

About 17 years after that abortion, the then-36-year-old mother of two was living in Texas and happily discovered she was pregnant again. But about 12 weeks into it, her health-care provider noticed an abnormality in the nasal bone, and began to do testing. “I found out my son’s brain had not fully developed,” Peterson remembers. “I was well educated by my doctor about what this would mean. They said I could terminate the pregnancy or continue on with a pregnancy that would end up in miscarriage or stillbirth.”

She decided to have an abortion. She wanted to do so right away, but quickly learned it wouldn’t be that easy. “Because of House Bill 2, which led to the closure of many abortion clinics in Texas, there was a lengthy three-week waiting list and I was up against the 20-week ban on abortion in my state,” she says. She also would have had to go through mandatory counselling, during which she would have been shown a picture of a fetus she knew she’d never get to see grow up into a person, she says. All this sounded like too much. At the convincing of a family member, she went to a clinic in Florida instead. Peterson is thankful she had the resources to travel out of state.

Without her abortion, she says she would have had to be put through even more “mental anguish” than she was going through already. “Not having that access would have impacted me mentally and emotionally for a long time, because I would be carrying a baby that I know would kick, a baby that I know is turning… I was literally walking on pegs, wondering, Will I miscarry today?” Peterson has spoken out about her story, especially in the wake of the Supreme Court draft opinion, because she believes no one should have to go through what she went through, and that all people should be able to choose abortion and tell their stories without judgment.

“I am a person,” Peterson adds. “I really speak out to share that I am a human being that had a human experience that did not experience humanity from a lot of people.”

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

How To Access Abortion Now — & If Roe Falls