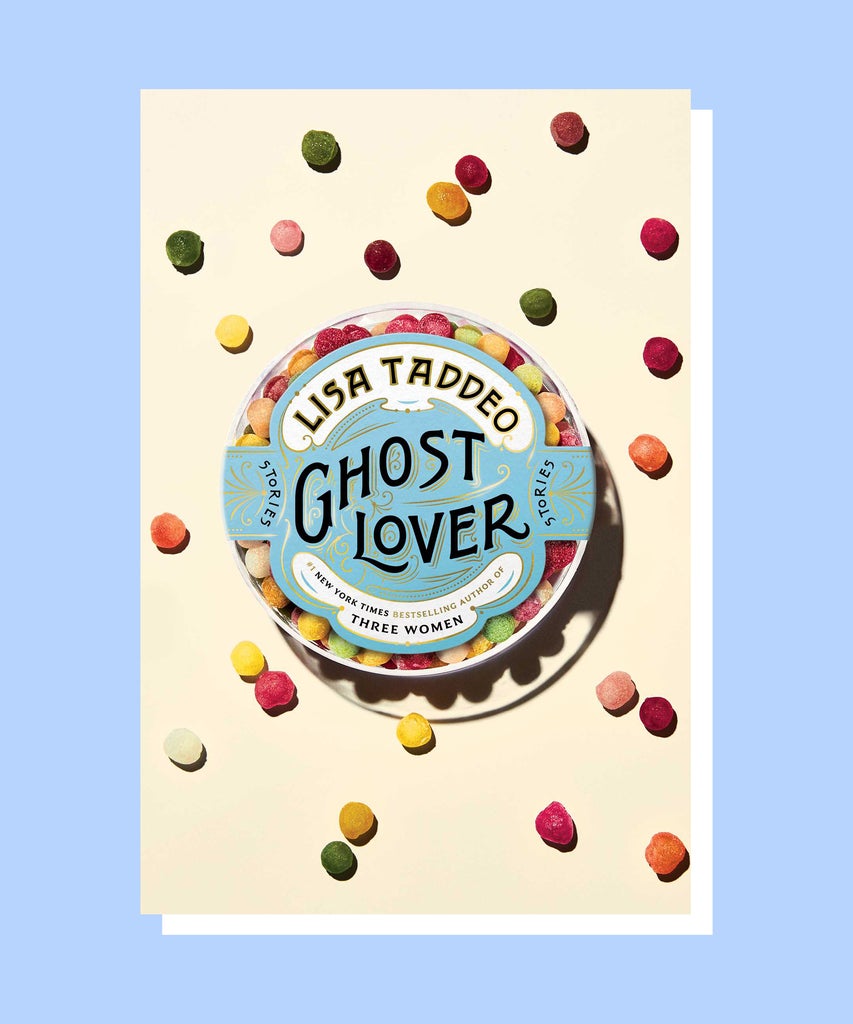

Competition and judgment — can friendship exist without them? If you say the worst possible thing about yourself that others could say about you, does it take away the idea’s power? How do we not let unrequited love wreck us? These are just some of the questions Lisa Taddeo explores in her new book of essays, Ghost Lover, out June 14.

The poignant collection completes something of a triad. Taddeo has also written one book of fiction, last year’s Animal, and one nonfiction project she reported over the course of eight years, the 2019 bestseller Three Women. As in her previous work, the collection explores the magnetic pull of our desires, how cruel we can truly be to ourselves (and our bodies), and the power of grief.

Here, in a wide-ranging interview related to the new book of essays, Taddeo talks about love, sex, friendship, and grief.

Refinery29: One of the themes in the essays is this competitiveness within friendships, and particularly among those who identify as women. Why do you think there’s so much inherent competition in some female friendships? Where do we learn this and should it be this way? How do these characters represent this?

Lisa Taddeo: “I base it on a lot of my own friendships and the friendships that I explored in Three Women. And I found that in these friendships, there is both a lot of beauty and joy and genuine love and compassion and understanding and comprehension of what the other person is going through — and there is certainly a rivalry, too. Not all the time and sometimes rarely and sometimes not at all. I feel like the younger people that I’ve spoken to — it’s not as prevalent as it is in their generation as it is in my age group, or it was when we were single. I think with younger women today, there’s so much self-awareness.

“But I think for single women who are looking for love — whether it be with a man or another woman or whatever — with your platonic friendships, there’s this sort of natural biological competition. But it’s not just that. It’s also in all of our storybooks — it’s even in Peter Pan. We’ve been fed this since we were children. And so, while I think there’s so much putative beauty to female friendship, I also think there’s a lot of that other stuff that we don’t really talk about because it’s hard to. Because your friends are the people you would talk about it with, and to even bring it up would kind of be admitting that there is something less than sanctified about your friendship — which is not the truth. It can’t be.

“Yet, it’s just reality. And talking about it in books makes it easier to digest and perhaps to move through. So that’s the way in which I have approached it. And that’s my hope for what it does, is put some stuff out there that’s in the cosmos.”

That’s an interesting observation you make – that there’s less competition in Gen Z friendship. But do you think there’s still judgment? I saw that come into play in a lot of the book’s relationships, particularly friendships.

“Definitely. Now, there’s less competition but more judgment. I was talking about this with Amia Srinivasan, who wrote The Right to Sex. What happens now is, we excoriate women for having the ‘wrong’ desires. We’re not allowed to like the ‘not good guys’ for us. There are all sorts of kinds of tacit new judgments that I think have come in. And the old judgments haven’t exactly left the building. The issue of having anything to say or think about someone else’s life as long as it doesn’t affect yours is kind of a baffling thing to me. And I think also one of the biggest problems we face as a society.”

You totally see that play out in the book. Like in the essay “Air Supply,” the narrator is judging her friend Sara almost every step of the way on their international trip, and then seems to later in life as well.

“Yeah, the narrator is judging Sara but then also there’s what Sara’s thinking about her friend. We each have our own shame and self-judgments. Sara in ‘Air Supply’ takes a lot of her own stuff and projects it onto her friend. The other thing that was interesting to me about that relationship is that it kind of goes back and forth between ‘who hates themselves less today’ or ‘who is doing the best thing by society’s standards.’ And that’s the thing that I think is what erodes friendships the most. So it’s the thing that I wanted to focus on.”

Why does it erode them the most?

“Thinking about each other in terms of who is ‘better’ or ‘worse,’ across the board, I think is the erosion of civilisation. We are all human beings. We’re all animals in the world, kind of trying to find our way. And the only purpose [this comparison] serves is to diminish someone else or elevate another person or elevate yourself while diminishing someone else — which is essentially what we do with racism and gender inequality. Any time we do that, it’s a negative.”

You mentioned shame before — you’ve written a lot about shame. In the book’s eponymous essay “Ghost Lover,” you touch on the complicated emotions around sexual abuse and shame. In that essay, the narrator was abused by her stepfather, and then she plans to tell the world about a separate sexual assault, by someone she dated and still has complicated feelings about. Before she publicly shares this, she thinks: “These people would not pity you for what your stepfather did. Or they would for a night and then they would think you are gross. They would think about you what you have often thought about yourself.” How does this essay aim to show the hurt and shame that sexual abuse can cause and the ramifications of that?

“There is the whole politicising of sexual assault — which sexual assaults are considered more egregious and who gets to be the decider of that. I often think about Mary Gaitskill’s essay in Harper‘s from a couple of years ago, where she talks about having been raped on three different occasions. One of them was a stranger rape. And another one was a man that was a younger man, I think a student of hers that she’d invited to her home. And she talks about how that [latter experience] was the rape that was the most insidious to her. It affected her the most because of her complicity. Then later in the essay, there’s a coda where she says that she had gone on to date the man after the rape and she had left that out of the original essay, knowing that people would judge her for it. They might say, well, ‘then that’s not a rape.’ All of that stuff that goes into sexual assault — all of our preconceived notions that we take into it. ‘Ghost Lover,’ is about a lot of things, but something very vivid within it is exploring the idea: What kind of sexual assaults do we feel are the ‘right’ ones? The ones that are not gross to talk about.”

In the “Ghost Lover” essay in particular, we’re really left not knowing what is going to happen next. She’s going to tell the world about this specific sexual assault, but we don’t get to hear how the audience responds. Was that intentional? I felt very emotional after reading that one and also really wanted to know what happened!

“That’s the general idea. I like when endings — when my own endings that I’ve written as short stories and when they’re in other stories that I read — when they are not cleaned up. I like not knowing what happens at the end of The Sopranos. It makes it feel like it lives forever, in a sense. And that’s how I feel about good short stories.”

I was thinking about that piece in connection with the Amber Heard and Johnny Depp trial, the outcome of which sets a precedent for people speaking out about assaults and sexual assaults and being sued for defamation. Do you think it all connects?

“I did not follow the trial as much as my interest level would have wanted me to. I do think that, in terms of speaking out or not speaking out, you never know when you’re going to be heard and when you’re not. I hope that people don’t look at that and think that they’re not going to be heard. I don’t think it’s a blanket statement for the way that we are going forward, just as I don’t think that Harvey Weinstein is a blanket cleaning up all things. I think both were gigantic markers of society in a way — they are not 100% indicative of the way that the future of something is going to go. Both fortunately and unfortunately.”

You’ve always written about sex so poignantly and you talk about both the beauty of it and the rawness of it and even the cruelty of it. I loved your line “his sexuality radiated like a space heater.” So melty! But then you also have lines that are so visceral, showing our complicated relationship with sex. Like: “Fucking her would be a planetary exercise, like he was poking between two long trees into a dark solar system and feeling only wetness and morbid air.” I audibly gasped when I read that one. How do these evocative and sometimes brutal lines reflect our society’s relationship with sex?

“That second line, in particular, I think it’s often the thing that a lot of my characters do — they say the thing. The worst thing that they could imagine someone else saying about them, as a sort of protective measure. It’s something that comedians do. It’s something that people who have learned how to exist in the world do. It’s a protective shell of a thing. And it was also a satirical comment on the way that we look at one another in the world

“I’m very interested in ageism. And I think that the way that young women look at older women and the way that older women look at younger women — often we look at each other like we’re a different species when we’re literally on the exact same trajectory. And for me, writing stuff like that shows the insanity of the way we treat age in this country specifically — as though it’s something that some people can help and other people can’t.”

I wanted to talk to you about the way the people in the essays talk about their own bodies. I think it comes back to that same idea: saying about ourselves the worst thing someone else could say. I feel like many of us think these negative things about ourselves at times, but wouldn’t admit it because we want to present to the world as good advocates of body positivity — or at least body neutrality. What was the collection’s intention in tackling these complicated issues? To show us we’re not alone in our thoughts?

“That’s something I have a lot of feelings about. The second you say something about your body in front of other people, other women, everyone’s like, ‘No! Don’t say that! You’re great, you’re beautiful!’ And it’s fine. And that’s great. And we should. That should be a reaction. But there’s also something to be said for letting someone feel what they’re feeling and there is something also to be said for how damaging toxic positivity can be.

“And when we do get prescriptive, [it can be harmful]. Say someone’s going through a breakup or someone that they love died and someone else is like, ‘Oh, you should go to yoga,’ ‘You should take up knitting,’ ‘You should read this piece,’ ‘You should do sound therapy.’ I have been in the depths of depression and I have tried to do all those things. And there is nothing worse than when you have tried to do all those things and you just kind of want someone to listen to you and they just give you another thing to do. And that’s kind of how I feel about the body stuff. It’s real. We do it. It happens. Until we get to a place where we don’t do it anymore, I don’t think that saying ‘the thing’ makes it happen more. I think it helps people who feel it to feel it less.”

You talk a lot about unrequited love in the essays. I really picked up on this, as a single person dating in their twenties. I was taken by “Forty-Two,” the story with the young woman — who’s actually named Molly like me — who’s getting married to this character who’s talking to another woman on his wedding day. And at the end, that man thinks to himself, “If only they knew how little time we spend thinking of them, and if only they knew how much we know about how much they think about us.” I’ve dated guys who probably could have said this. How do we grapple with that unrequited love?

“Acknowledging the problem is the first part of dealing with it. And I’m not saying that it’s a problem to think about someone else more than they think about you. It happens a lot. Though, if I were trying to counsel my child on how to deal with love going forward, I would definitely counsel her against it. But it’s okay. It’s okay to have all those feelings and we should be able to be there for each other during them. And part of why I wrote those lines, in particular, is because: what’s the worst possible thing that we think is happening, right? Like what I said before, if we can say that thing out loud — whether or not it’s true — to me, it’s a form of healing.

“And, in this book, in particular, I was not concerned with the happy ending. I was concerned with the millions of sad endings that come right before it. It’s almost a primer on how to get through those.”

Unrequited love isn’t the only kind that’s grieved in the book — there’s also Fern, who’s lost her parents in the story “A Suburban Weekend.” Her grief for her parents seemed as boundless as her love for them. In Fern’s case, the loss made her what some would call reckless. How is the book showing us grief up close, especially when it impacts us when we’re young and vulnerable?

“That story was probably the closest to my story of my life. In that story, Fern has lost her parents and I lost mine. And I remember I was very similar in the sense that — I didn’t know what I was living for.

“I didn’t have anyone to talk to back then. Certainly, there were support groups, [but] I didn’t go to them. I hung out with my same friends and we did the same things that we had always been doing. But now I was doing it with this hole. And it was really weird and hard and I was kind of on a different planet than everybody else. That’s what I wanted to show in that one.”

I can tell you put so much heart into that story. What would you want someone going through something similar to feel at the end of reading that essay?

“That somebody is going to care about you on the other side.”

This interview has been condensed for length and clarity.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Lisa Taddeo On Animal, Her Debut Novel