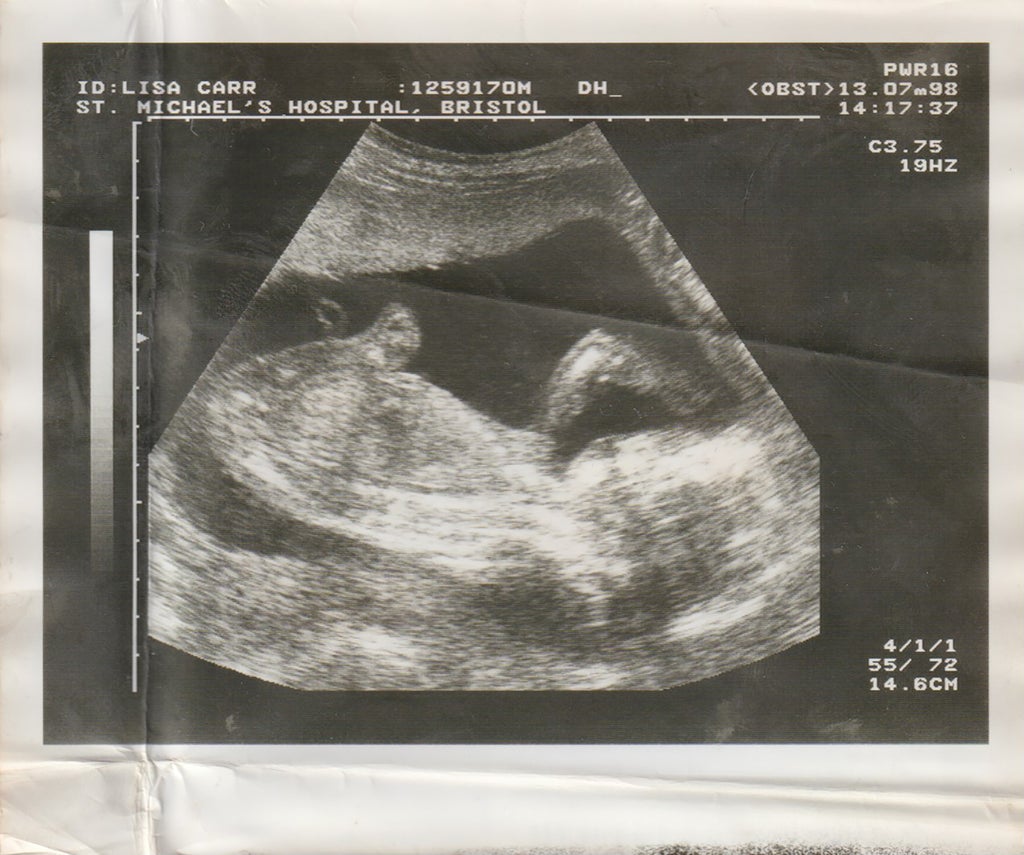

“I was two weeks into my master’s course when I found out I was pregnant,” says 24-year-old photographer Jade Carr-Daley. “At the time, I had already started a body of work focusing on my relationship with being both British and Jamaican but it was moving slowly and, in all honesty, I hadn’t been feeling that strongly towards it.” While searching for a topic that felt more fulfilling, Carr-Daley began taking photos to document her transition into motherhood – just for herself at first, until three months later when she finally decided to acknowledge what was staring her in the face: this documentation should be her major project. “It seemed so natural and free-flowing,” she says, “like this was the project I was meant to make.”

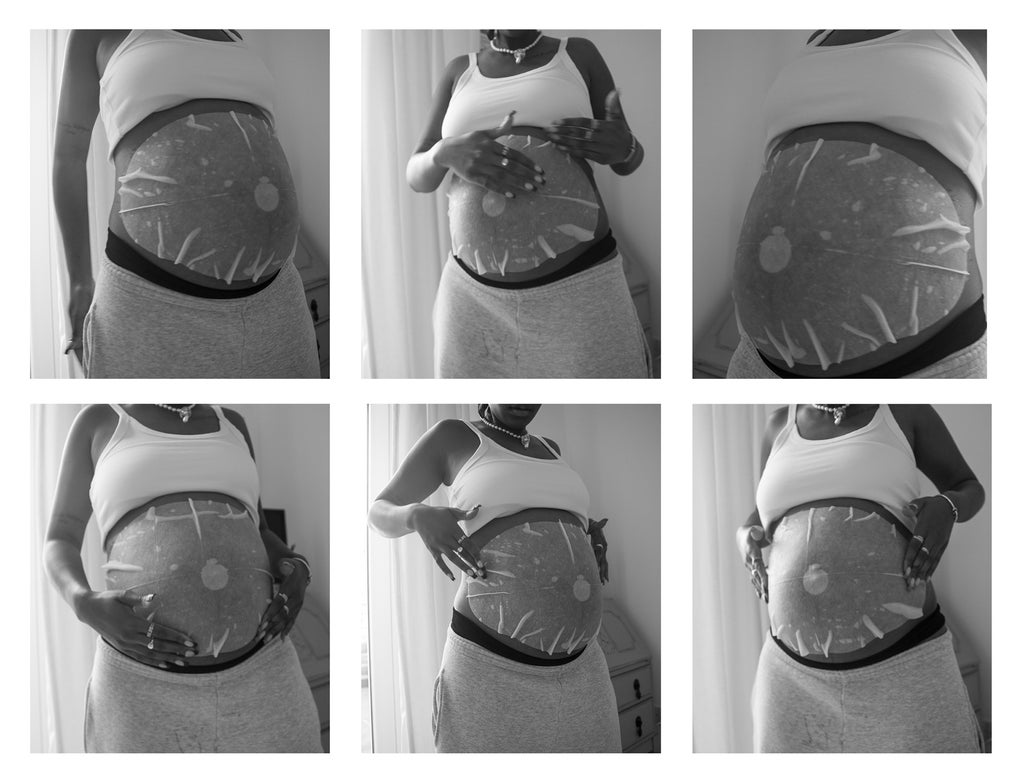

The resulting photo series is entitled Not Ready Not Steady Go! and it’s full of gorgeous, intimate pictures evoking the spectrum of emotions that flood in with impending parenthood. Across the series, we watch as Carr-Daley’s body adapts to accommodate the new life inside her, and as her relationship with her partner evolves. In both black and white and colour images, moments of tenderness between the two of them are fused with a sense of soft anticipation. Of course there are anxieties that come with being pregnant, and Carr-Daley didn’t want to shy away from visualising those, too.

In social media, pregnant bodies are often manipulated and edited to fit into society’s ideal, perfect pregnancy and then when Black pregnant bodies are introduced, they are edited even more, or portrayed in a way that fits into society’s white beauty standard.

JADE CARR-DALEY

“The first three months of my pregnancy were the hardest,” she recalls. “At the time, only my partner and I knew and during this time, I experienced some issues with bleeding, spent a lot of time being assessed and was constantly worried something was wrong or that I had done something I shouldn’t have. As a result, I fell into a sort of hole, and found it hard to talk about my feelings. So when I started photographing myself and my environment, it turned into a form of self-therapy for me. Instead of being in that moment and state of mind alone, I was able to photograph it and this made it easier to understand how I was feeling, to see my physical changes and to better articulate how I felt about certain situations to my loved ones and friends.”

Growing up in Bristol, Carr-Daley began life in an area of the city called Easton, which she describes as particularly multicultural, before moving to an area called Henbury when she was still a child. She still lives there today. “This place was very different to Easton,” she says, “mainly because, at the time, the area was predominately white and my family were a minority there. I was subjected to racism a few times – not anything close to the stories my parents or other family members would tell me but more through microaggressions, body language and sly comments made by children in the area or by people on public transport.”

By the time she got to secondary school, Carr-Daley was back with kids from all different backgrounds and that’s when she really started to feel around the edges of her identity. She took photography at GCSE level and then went on to study it at Bath Spa University. “That was probably the most crucial moment in my practice. I was the only Black student on the course and there were countless times I would feel out of place or that the work I was creating didn’t fit in,” she says. “In my second year, I thought about dropping out but a teacher of mine wouldn’t let this happen. He could see my potential and often said, ‘We need more voices like yours’.” And so she felt empowered to apply for her master’s course at UWE, beginning her studies there in 2021.

I would have liked to have seen more Black women in healthcare. When attending appointments, sometimes I didn’t feel truly comfortable, understood or listened to, and I constantly felt like I wasn’t always in control of my body.

Jade Carr-Daley

Alongside making her physical work, researching the project topic became crucial to Carr-Daley’s process – chiefly because she found it very hard to find other projects documenting the experiences of Black pregnant women. This drive also came from her personal experiences in the healthcare system and the exhaustion of having to advocate for herself constantly. “I would have liked to have seen more Black women in healthcare. When attending appointments, sometimes I didn’t feel truly comfortable, understood or listened to, and I constantly felt like I wasn’t always in control of my body,” she says. “I felt as though certain midwives and doctors could only help to a certain degree because the basis of pregnancy and women’s bodies for years has been taught from a white standpoint, and that can make things hard.” Then there was the matter of her age, which meant she often felt talked down to, alongside the difficulties of being a third-generation mother in her family. “I felt judged sometimes with how I wanted to approach my pregnancy – deciding not to cover my stomach in public places, for instance, and wanting to give birth at home or at a midwife-led centre with a water birth,” she says.

When asked how it felt to turn the camera on herself and her relationship, Carr-Daley is clear. “To put it bluntly, I hated it,” she says. “I felt very vulnerable and uncomfortable in front of the camera, and in some of the images you can see that I would often use different objects to cover my face. The further I got into the project, though, the less I started to care.” Her partner felt more comfortable in front of her lens because she’d photographed him so often before, although they still had to have a conversation about what he was comfortable with during this new experience.

“During pregnancy, a lot of focus is on the woman – and for good reason – but sometimes, from my own experience, the partner’s feelings can be overlooked. Becoming a parent is such a big change for both people involved and sometimes we can forget to check in on them too, so it was really important to ask him what his boundaries were. In this way, I would say it became a collaborative project between the two of us at times, as he would often photograph me too, and whenever we worked together, we would always converse about the reasons behind the images we were making, and then those conversations would turn into deeper ones about our fears as new parents, things we looked forward to, what our baby would look like, and our plans for how we would raise our child together.”

Carr-Daley gave birth to her son, Knox, in early July 2022; he’s 8 months old now. One of her favourite images from the series is a close-up of Knox’s little feet, framed by her own legs. It’s called “The Big Question?” and you can see a little puddle of dribble on the bedsheets beneath them. “I took this image on my iPhone and it was a happy accident because the dribble looked like a question mark, which made me think of the question: ‘What’s next?’ As in, what’s next for this project, for myself and for my new family? Right now, I’m just taking it one day at a time, learning how to be Knox’s mum and how to balance being a photographer and a parent. I love every day that being a parent brings, even on the days that make me feel like complete shit. I definitely want to create more work around motherhood and our health system, and I would love to start speaking publicly on the themes within this project because they are just so important.”

Ultimately, Carr-Daley wants this work to contribute to the conversation around representations of the Black pregnant body. “In social media, pregnant bodies are often manipulated and edited to fit into society’s ideal, perfect pregnancy and then when Black pregnant bodies are introduced, they are edited even more, or portrayed in a way that fits into society’s white beauty standard,” she says. “With this work, I want people who are either going through a similar situation, or have already gone through this, to feel seen, related to and understood, and I want more conversations when it comes to the importance of representation, especially for people from Black or coloured backgrounds. My advice to anyone going through this for the first time is to be patient with yourself, and to learn and understand your rights as a woman going through pregnancy. Always remember you have the right to say no.”

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

These Photos Are An Ode To Black British Culture