I never said: “I want to be white.” Never dreamed of it nor wished for it, actually. I grew up in a Black neighbourhood with a proud Black family who taught their children — me and my sister — to love ourselves, our skin, our hair, our people. African art adorned our walls and Black folktales flowed through our ears at the dinner table. Many would say I relished in my culture and identity as an African American, and while it’s partly true, I did grow up in the early 2000s when there was no DEI movement in Hollywood. Racial slurs and microaggressions were considered “drama” or plot points (especially in reality TV). The Proud Family was one of the few Black cartoons on air, and as for movies made for and by Black people, Tyler Perry’s Madea series was the most popular. And even those pieces of pop culture took a backseat in the mainstream to programs that centered whiteness. No amount of pro-Blackness at home could undo the misguided programmed messaging that white was more beautiful, more deserving, more everything.

It wasn’t like I hated myself. I like being Black — no, love being Black. And, yet, somehow, when the opportunity to be anything — anyone — else arose, I always chose white.

The first time was in 2007 when my mom took me to the local Blockbuster and bought the Bratz: Rock Angelz video game for my PS2. There were four protagonists to choose from: racially ambiguous Jade and Yasmin, the sole white character Cloe, and dark-skinned Sasha. I always played Cloe. Sometimes Yasmin, rarely Jade, and never Sasha. Cloe was just more like me, I often said to my sister. (Unlike my 7-year-old self, she always chose the Black video game characters). Cloe was dramatic, boy-crazy, and an anxious wreck. That was me to a T. So what if the avatar was blond with fair skin, blue eyes, pinkish lips, and loose hair and looked nothing like me?

But then it happened again a year later with Animal Crossing: Wild World. I had just got a Nintendo DSi for Christmas along with a handful of games from GameStop. It was my first time creating my very own avatar, and I decided on a Kim Possible lookalike. To be fair, the old Animal Crossing games didn’t have the deep skin tones and ethnic hairstyles they do now. But while it was nearly impossible to recreate my skin tone and textured hair in the game (you had to “tan” in the sun to become darker — it was that bad), I could at least make a character racially ambiguous or as Black as they could be. But I didn’t. I was fine playing my white avatar. More than fine, actually. I loved being in a digital space so unlike my own reality, where my avatar looked just like everyone else — or, err, mostly like everyone else, considering half of the non-playable characters (NPCs) were animals.

In 2012, I got my first PC. The Sims 3 had dropped three years earlier, and it was all my tween self wanted to play. Unlike Animal Crossing, there were more custom features to choose from, including a colour wheel that made deeper skin tones more accessible, five ethnic hairstyles, and sliders that added more customization to the eyes, lips, and face. The bar is in hell, I know, but hey, it was 2012.

My first ever Sim was white. But unlike my previous avatars, I named this Sim after myself. Melanie The Sim was thin with pink pale skin, covered in freckles, and had blue eyes and long brunette hair. She had a white boyfriend, who became her white husband. They had white children, and well… you know the story. When Melanie The Sim died of old age, I played her children and then her children’s children and so on. It wasn’t until I was 18 when I realised, never in my in-game multi-generational family, or any of the other families I created and played with, did I make a Black character.

I wish I could blame it on being an adolescent, but I can’t. My sister, a fellow Simmer, would always ask me why. What was this fascination with being white? I didn’t want to be white in real life, I replied again and again. But, I did, though, right? Sure, EA, The Sim’s parent company, had unrealistic Afrocentric features like patchy dark skin and oddly shaped afros that look like cauliflower, but they did have options. Bad ones, yes, but choices nonetheless that I could have made to create a Black Sim. And yet, in my virtual world where I ventured to escape reality, I chose to be someone so unlike my real self; someone who was always seen on TV, in film, in my dolls, in the descriptions of my favourite novels. I chose to be white in my video games because I was replicating what I’d been told in media: being Black was the anomaly; it was “wrong”; it was “inhuman”; it was “ugly”; it was “criminal.”

There was no reckoning or traumatic event that stopped me from creating white characters. Maybe it was going to a predominantly white college and being around mostly white people for the first time, or it was the summer of 2020 when I learned just how much white folks didn’t value Black humanity, but when I launched Sims 4 in November 2023 after a five-year absence, I couldn’t imagine creating anything but a Black woman.

I deserve to be there — and seen — with my brown skin, dark brown eyes, nappy edges, and kinky hair.

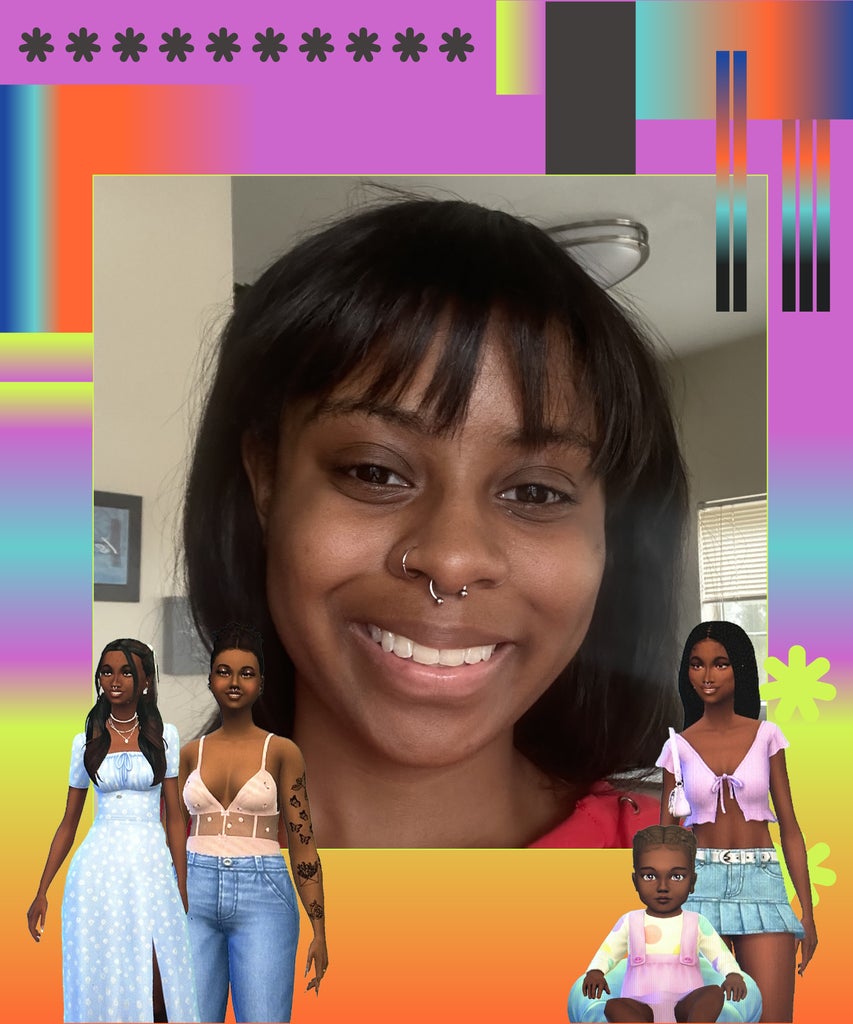

My first Black Sim was named Salem Farrow. She was the idol my inner child never knew she needed. She was the colour of deep warm brown, a similar hue to my complexion, and had wild kinky curls and a plethora of floral tattoos and piercings adorned on her skin. Unlike my previous Sims, I was meticulous with her creation, so much so that it took me days to create her. Mostly because I spent half of the process scrolling through Tumblr, looking for natural hair custom content, prefixed skin tones that mirrored the colour of my complexion, melanin-friendly lipsticks, and natural French tips that blended just right with any deep skin colour. But I didn’t mind the detail or the effort — Salem wasn’t just another Sim to me. For one, she was the leader of my Legacy Challenge (a playstyle where you start with one Sim and build a family that spans generations) but more importantly, she was the culmination of the love and care and appreciation I learned to give to myself.

Being a Black person, especially a Black woman, requires consistent, immeasurable, and unconditional self-love, as the world subtly (and sometimes bluntly) tells you lies about your hair, your body, your skin, and your intellect. And so, Salem and the many more Black Sims in my gallery were love notes to myself, of my beauty, confidence, grace, and humility. Small tokens of appreciation and validation that I gave myself because society and all of its mediums were never going to.

This is why representation matters. Not just so Black and BIPOC folks can see themselves, but also to understand they’re deserving of a place in this world, or in a digital one. It’s why Black custom content creators like Xmiramira, whose 2016 modpack offered Sims players a wider range of skin tones, hairstyles, and melanin-friendly makeup looks, and Ebonix, the co-founder of Black Twitch UK who became the first Black woman in the UK to be a Twitch partner, are necessary; why Dove’s Code My Crown — a tech training manual released in 2023 that gave developers the tools to create realistic ethnic hairstyles — should be mandatory, not optional; and why white engineers and designers should be trained and equipped with incorporating diversity and inclusion in games, instead of relying on their (often lesser paid) Black peers.

What I do know is that I love myself both IRL and online. All of my avatars from Starfield to Skyrim are Black. The Sims 4 too. And while part of that is because of the inclusive hair and skin tones in modern gaming, it’s also because I can’t imagine a world in which I don’t exist. Because I deserve to be there — and seen — with my brown skin, dark brown eyes, nappy edges, and kinky hair.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

The Sims Was Our Sexual Awakening — & It Still Is