It’s no secret that South Asian women have faced an incredible amount of scrutiny about their appearances for generations. While social media’s “mute” function is handy to shut out negative influences online, there’s sadly no escaping the intensely personal remarks made by your own family.

It’s the unfortunate norm in South Asian culture. We all have that aunty — let’s call her Reena — who just can’t help but throw out a scathing comment about your skin, hair or weight in front of everyone. Nobody is safe from the wrath of Reena aunty, and I’ll bet that almost every South Asian woman has a family member making snarky digs about how they look, without any care for how that might make her feel.

Sunita, 46, knows this all too well. “I was bullied by my own mother-in-law during my pregnancy about my weight gain,” she tells me, confessing that she spent a lot of time crying to herself and unable to answer back. Taunted for what she was eating, Sunita resorted to having dinner at work before coming home and didn’t tell anyone what she was going through. The mother-in-law/daughter-in-law dynamic can be difficult to navigate, but she was feeling too low to challenge things. “I had to be induced one month before my due date as I think I was so disturbed. It affected me badly,” she says.

There are a scary number of

‘aunties’ who are comfortable enough — actually, empowered — to make the younger generations feel like crap.

This is just one example of how pervasive unrealistic beauty standards seem to be embedded in our communities. Like Sunita, I’m all too aware of the toxic pressure to have clear skin and a “perfect” body. I still refuse to wear my hair up for family events, keen to avoid criticisms around a keloid scar on my jaw. The predictable comments ring in my ears: “God, what happened there?” The harsh words get louder so that the other aunties can hear, until they join in, too. “You should get that awful thing cut off! Have you considered going to a doctor?” It might sound dramatic but this is the kind of ordeal it can turn into: Being trotted out across all the aunties in the room until they can agree on a medical diagnosis despite not having a single qualification between them. And no, being judgmental and insensitive doesn’t count.

Not only are South Asian women expected to adhere to unrealistic beauty ideals, but we also have a scary number of “aunties” who are comfortable enough — actually, empowered — to make the younger generations feel like crap. This is an extremely toxic feature of what is otherwise a beautiful culture, and no doubt feeds our insecurities. But in a time where the wider beauty industry is encouraging us to love ourselves, it’s clear that there is some serious self-reflection needed in the South Asian community. It begs the question: Are young South Asian women ready to break this toxic cycle and adopt a safer, kinder environment, or are we all doomed to become a Reena aunty in the future?

While heavy criticism around looks has mostly come from older relatives, friends have told me that similar judgmental comments are now coming from their millennial- and Gen Z-age mates. Priyanka, 33, tells me that her friends — roughly in their late 20s — are seemingly rearing their inner Indian aunties, much to her disappointment. After Priyanka posted some holiday pictures to her Instagram story, one friend WhatsApped her asking if she had gained weight, noting that her face “looked rounder”. Priyanka says that she was already feeling self-conscious about her body, and her friend’s message made her feel even worse.

Sadly, Priyanka is often on the receiving end of these types of comments from women her own age. Similarly, healthcare professional Nikita, 30, says that while criticisms predominantly come from the older women in her life, she has also received comments from peers. Nikita recalls a moment where her friend commented on her “spotty skin” and “darker complexion”, with an underlying tone of “relief” that she didn’t look the same.

Perhaps it isn’t all too surprising that these judgments are filtering down to the younger generation. As a culture, we’re obsessive about body image. For example, we’ve been poking fun at the “Indian fatty” for years. Ladoo’s character in 2001 movie Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, didn’t stand a chance — a once-chubby school kid only lauded for his looks and valued by peers once he glowed up in his 20s. Even the writers in Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani, which took Bollywood cinema by storm just last year, couldn’t resist a similar storyline. Attitudes to body image have changed significantly over the years, but in the recent movie, Gayatri (nicknamed Golu, which translates as ‘round’) was rejected romantically on the basis of her weight. Is it any wonder that a younger generation of South Asians are internalising such messages?

Part of me is holds on to similar restrictive beauty ideals today. At nearly 30 years old I know firsthand what hypercritical comments can do to diminish self-esteem. With that in mind, I wouldn’t dream of repeating them to my future children. Worse still, I don’t want to imply that we must conform to another’s unattainable version of beauty. It’s the aunties who need to change their ways — not us.

@hasinikay Curly hair is often criticised in the desi community but don’t let thst criticism affect you. Love and nourish what you were blessed with and it’ll flourish #curlyhair #curlygirl #curlyhairroutine #curlyhaircheck #desigirl ♬ original sound – skanda

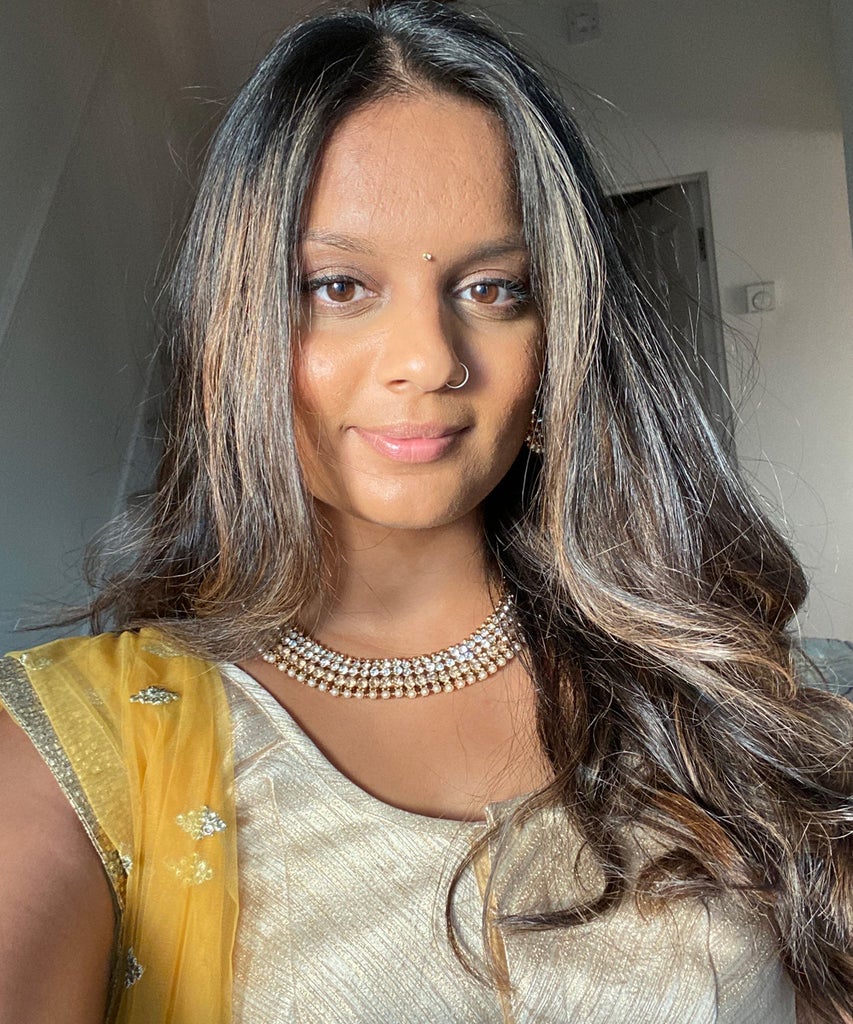

Happily, the rejection of the shady aunty trope is bubbling on social media, with accounts such as Brown Girl Gang and TikTokers like Hasini Kay, encouraging the ownership of beauty and championing South Asian women to define their own worth. The message is clear: It’s important for us to redefine what beauty means for the sake of future generations of South Asians, because a throwaway comment can plague you for a long time, as beauty and lifestyle influencer Hemali Mistry tells me.

Growing up, Mistry faced negative comments about her weight, which has contributed to her poor relationship with food, something she discovered in her mid 20s, when she noticed her anxiety around eating in public. “Now I’m in my 30s, I’m trying to build healthier habits around eating but it’s honestly been a struggle,” she says. This is why she uses her Instagram platform to spread awareness of the more challenging aspects of South Asian culture, with her GRWM (get ready with me) videos highlighting topics such as facial hair, makeup and ageing. Mistry often questions how normalised it is to attack each other’s appearance and be openly hateful towards your own family in the South Asian community. “If you were ever to say that s*** back to them, all hell would break loose,” she says calling out critical aunties and uncles.

When [criticism] comes from your own friends or family, it’s even more difficult to overcome. After all, your circle is meant to protect you.

Mistry advises taking the time to question why you think or feel a certain way about your appearance. “Often, you’ll realise these thoughts aren’t actually your own, but instead come from the system and culture you’re raised in,” she says. Mistry has done her own share of unlearning. “Thankfully, at some point I realised this is not who I want to be and that I was turning into the exact type of aunty I always hated,” she admits.

Likewise, dermatology GP Dr Pyal believes that comments on appearance “often come from a place of concern but end up being quite hurtful.” As a mother of two young girls, Dr Pyal hopes that things are moving in the right direction for future generations. When faced with such comments, however, Dr Pyal points out that protecting your self-esteem while maintaining family relationships can be a rocky road to navigate. As such, she recommends setting boundaries by firmly yet politely explaining that hurtful comments about your appearance make you feel uncomfortable. Some suggested replies are, “I appreciate your concern but I’d prefer not to discuss my appearance,” or “Comments like that really hurt and affect my self-esteem,” advises Dr Pyal.

In an ideal world, we’d shrug off criticism and keep it moving, but when it comes from your own friends or family, it’s even more difficult to overcome. After all, your circle is meant to protect you and build you up. In a positive move, a new generation of South Asian parents are proactively breaking the cycle and detaching themselves from toxic beauty standards for the sake of their children. It feels like a turning point is on the horizon. Dr Zahra Fazal, aesthetic practitioner and director of Harley Street-based Tweak Facial Aesthetics sees body dysmorphia in her patients and is “conflicted” knowing that her industry “can be a big part of the problems young girls face.” Nonetheless, she is proactively protecting her three-year-old daughter Leya* from the negative effects of these types of comments. The first step is confronting her own demons, she says, and “undoing the years of being told how and what I should look like.” Despite working in the aesthetics industry, Dr Fazal makes a conscious effort not to bring her work home or comment on appearances — positively or negatively — in front of Leya in a bid to protect her confidence. “When we praise her, it is for her personality, her intellect, her behaviour, her hard work, her sassiness,” she says.

Dr Fazal recalls having firmly told a family member — who made a comment about Leya’s thighs — that she should stop, explaining how damaging these types of comments have been on her own confidence. The family member in question got the message eventually, but Dr Fazal adds that she had ended friendships as a result of similar negative views. “I would not let someone else’s body issues [reflect] onto my child,” Dr Fazal says, adding that it can take a lifetime to silence those voices. Dr Fazal has battled years of disordered eating and excessive exercising. She spent the majority of her teens and twenties never showing her legs and avoiding dresses above the knee at all costs. “I wish I’d enjoyed my body when I was younger,” she tells me. “Instead I wasted those years being self-conscious and having a very poor relationship with my body.”

Nikita, 30, is also actively thinking about how she might have to navigate such situations when she has children, particularly a daughter, who she would never want to be reduced to tears like she has been on so many occasions. She recalls being at family events and receiving comments like, “What’s that on your face?” in reference to her acne, alongside unsolicited advice about what she should (or shouldn’t) be eating to remedy her skin. When you’re already so insecure about your acne, having it pointed out in front of people by your own relatives is disheartening, says Nikita. “I hope [my future daughter can] adopt a ‘who gives a fuck’ attitude more than I do.”

Even when equipped with the right tools, young South Asians are torn on whether collectively challenging — and ultimately rejecting — unrealistic beauty standards will impact the community in a meaningful way. After all, words like “insecurity” and “mental health” are not in the vocabulary of the older South Asian generation. But the change starts with us, says Aarti, 29. “It’s our responsibility as the younger generation to challenge everyone, including those older generations who can’t see beyond their traditional views. We have the ability to voice and translate the western ideologies for them to understand,” she says. Mistry echoes Aarti’s sentiments and urges the younger generation to try and break free from these “toxic” mentalities.

Seeing what the new generation of South Asian parents are doing to shatter years of toxic hatred gives me hope that my children will similarly be protected by their family — and by me. Their self-esteem will be built up rather than torn to shreds. They can wear their hair however they want at family weddings, and the inevitable tears around feeling insecure will simply be par for the course of growing up, not off the back of an awful relative who can’t keep their hateful views to themselves.

*Name has been changed

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

When Will Pressure Of The ‘Brown Girl GlowUp’ End?