For Black History Month UK, Unbothered takes a look at the tangled history — and future— of Black identity, beauty, and culture. We’re giving wings to our roots…

“No one gets left behind!” is the motto of the run club I attend every week (yes, I am one of those running types). “What are we?!” commands Hermen Dange, the founder of Made Running Club, loudly to hundreds of neon-clad runners. “A FAMILY!” we yell back. And we believe that we are just that: a family. Then, together we run 5K, supporting the people we overtake and cheering people on as we cross the finish line. This is one of the highlights of my week. It’s a run club designed for everyone, of every ability and walk of life but it is notably led by a group of young Black people in Manchester who wanted to create a space for self-improvement and community. After serving time in prison, Hermen Dange created Made Running to help himself and those around him. Speaking to local media earlier this year, he said: “It became about building a community, a family. It’s not just about me anymore; it’s about helping others.”

As we clap and dance to Made Running chants, blast music, and hear testimonies from group members who share their personal growth journeys, I can’t help but be reminded of the (very Black) Pentecostal churches, youth groups and community centres I grew up in but no longer attend — similarly, there is a palpable sense of communion and high energy that leaves you feeling uplifted. Whether intentional or not, this run club is a very melanated experience. And I love it. I’ve missed it.

The desire to find and form communities where I feel seen, represented and uplifted has been strong lately. Alongside Made Running Club, I also joined a Black-women-led book group, Book Hive MCR, where we read globally and join in with Black lady “mmmmms” when one of us drops some literary wisdom. These groups aren’t one of a kind but part of a rising and welcome trend among millennial and Gen Z folks wanting to foster IRL connections in the digital age. For Black and marginalised British people at the helm of some burgeoning social spaces (such as Black Girls Hike, Peaks Of Colour and Circle Social in London) these groups were also born to diversify the UK’s social scenes and fight the loneliness epidemic amongst Black people in this country.

This Black History Month UK, I am reminded that Black community spaces have played an essential role in our liberation, societal progress and change.

Young Black people in the UK are said to be lonelier than ever—whether we live in the anonymity of big cities or isolated in small homogenous rural towns. In 2022, research by the Mental Health Foundation claimed that young Black people were more likely to experience loneliness than the general population due to racism and social inequalities. Others blame the long-term impact of the pandemic and the dystopian shift towards digital relationships over real-life connections.

It’s also suggested that the lack of safe spaces outside of work (where for many minorities racial and social inequalities are most felt) and home have contributed to feelings of isolation and otherness amongst young Black people. These are called “third spaces” — places you frequent outside of home and work. According to BBC News, American sociologists Ramon Oldenburg and Dennis Brissett first defined them in 1982 as public spaces crucial for neighbourhoods as a space to interact, gather, meet and talk. In the UK, I would argue that Blackity-Black third spaces — created for and by us — have long been crucial to establishing a sense of belonging in a society where we are often othered.

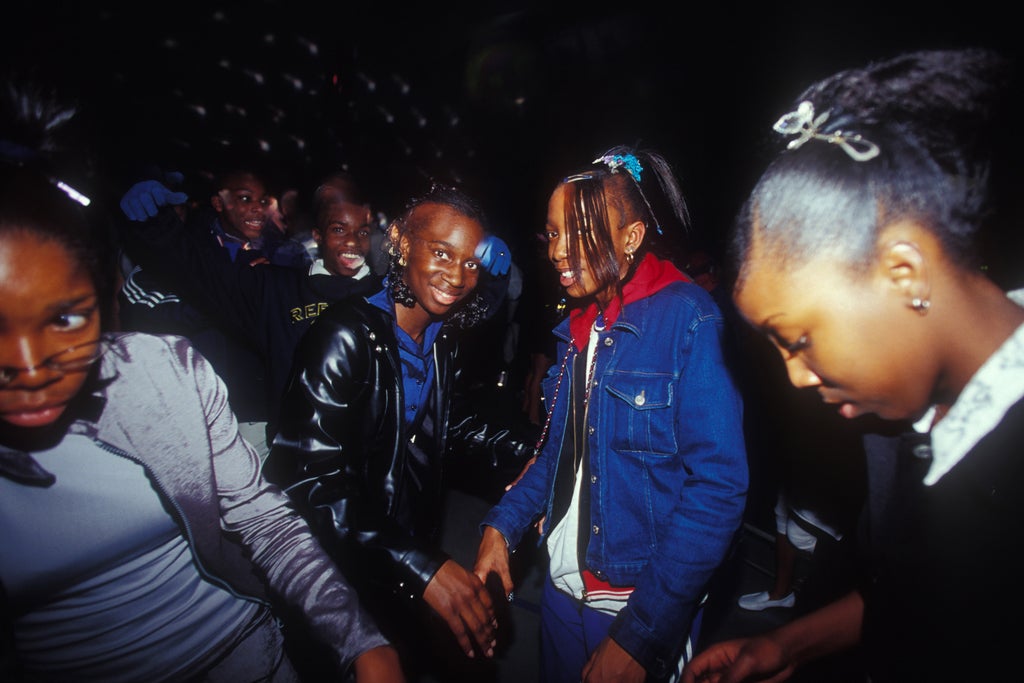

By the early 2000s, as Black teens were demonised by discriminatory stop-and-search policies, youth and community centres gave a generation of young Black, brown and white working-class kids somewhere safe to go.

The continued rise in Black social groups is helping to foster a sense of community and belonging that has arguably been lost in recent years. Following the recent race riots in the UK and the palpable feeling of financial uncertainty in Britain, finding space for unbridled Black joy has been paramount. I am envious of the villages my parents, aunts, and uncles were always part of as children of the Windrush; Blues parties and sound systems, pardners (where small groups came together and shared from the combined pot of money weekly), the early days of carnival.

This Black History Month UK, I am reminded that Black community spaces have played an essential role in our liberation, societal progress and change. From as early as the 70s, community centres emerged as a lifeline for Windrush and immigrant families (away from the familiarity of churches and unwelcoming British pubs) as well as centres for the arts. Britain’s first Caribbean centre, the Keskidee Centre, was opened in 1972 in Gifford, Islington set up by Guyanese-born architect Oscar Winston Abrams. “Throughout the 1970s the centre became a thriving cultural venue, and for several years it was the only place to experience Black theatre in London,” according to research by the Trust For London. “During its time, it was visited by Bob Marley and Nina Simone.” The Keskidee Centre was also an important cultural space for Islington’s Black teenagers, and for political discussion as they rebelled against oppressive structures, and violent and racist policing across London.

Community centres that serviced the needs of marginalised people and Black teens opened up throughout Britain. These centres are still valuable in helping forge racial equity in Britain; they give access and support to finding suitable housing and childcare, they specialise in culturally specific care for our elders and organise local events that support the wellbeing of individuals and families. By the early 2000s, as Black teens were demonised by discriminatory stop-and-search policies, youth and community centres gave a generation of young Black, brown and white working-class kids somewhere safe to go.

I grew up in inner-city Manchester in a middle-class neighbourhood but had close family connections to Hulme and Moss Side (an area negatively associated with gang violence and referred to as “Gunchester” in the 90s, but it was where I made joyful links to my West Indian culture). Growing up in the noughties, I would attend Hulme’s local youth clubs and “playschemes” where I learned how to dance, sing in public, play team games and get rid of any nervousness through forced group participation activities. In Manchester, I credit the Zion Centre, a community centre more than 100 years old, for giving me space to express myself in dance and spoken word. We were all mainly inner-city kids from state schools whose parents needed us to be occupied over the summer holidays. I built tough skin in those youth clubs; and learned to verbally tussle with cheeky but lovable boys who wanted to be grime MCs. I owe these years to building a sense of belonging in my teenage years when I went to a predominantly white high school.

These youth clubs largely relied on willing volunteers and social workers to offer mentorship and gave meaning to the saying “It takes a village to raise a child”. Many famous Black British artists such as Daniel Kaluuya and Stormzy thank youth clubs and community arts programs for giving them their start in music and acting. Upon launching his own community centre MerkyFC earlier this year, Stormzy told BBC Sport, “I had a youth centre where I would go and make music…To me, it’s about sowing a seed, which sounds like a parable, a bit like a fairytale, but I don’t think people understand how powerful it is and how valuable it is.”

I took for granted the lasting impact and legacy of community groups and youth centres. There are far fewer government-funded and charity-run third spaces for young people in 2024. Earlier this year, it was reported that huge cuts to youth services in the UK (around 60%) meant a thousand youth centres have closed. This risk creates a “lost generation” of young people, especially within deprived areas, unable to access vital support at a crucial time in their lives. The loss of these centres has been felt deeply by the communities that relied on them. New research by Spotify in partnership with charity Mentivity, says 76% of young people believe youth clubs offer them a safe space and 74% of young people believe youth clubs reduce feelings of isolation. Sadly, 64% of the young people surveyed believe the closure of youth clubs has a negative impact on the younger generation and 43% of young people feel like they aren’t part of a community or have a sense of belonging.

For those of us who grew up in youth clubs, creating new spaces for creation and expression as adults has become a new mission. Efia Mainoo is the founder and CEO of BlackOwned Studios + Marketplace in Manchester, a co-working space for Black hair stylists and creatives helping to address the disparities in the beauty industry. The studio also transforms into space for events such as Black-owned wine tasting, open mic nights, art classes and more.

“Everything that I wanted to create in the space has been used to spark joy and to really centre the Black experience,” Mainoo tells me during one of her events. “The world is heavy as it is and when you step outside the walls of the studios, the world is going to treat you however they’re going to treat you, but I want to make sure that you can come to a place where you know that you don’t have to explain things, where people will understand what you’re going through, or at least try to understand what you’re going through.”

“It just made sense to make sure that my business also amplified [the joy of Black community spaces], because I don’t think it’s spoken about enough,” Mainoo continues. “The media will focus on the whole range of issues and problems, especially the racism that’s going on in the country and it’s important to talk about, but also holding space for the laughter on the other side of that scale is so important and means everything.”

With the onslaught of new Black third spaces in my hometown and beyond, I have been transported back to my happiest time in my youth. Over time the feelings of loneliness (even when you’re surrounded by people) have begun to dissipate because I have found my people; the incredible Black individuals holding space for us and the culture. Long live community centres past and present, the social glue that holds us together.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?