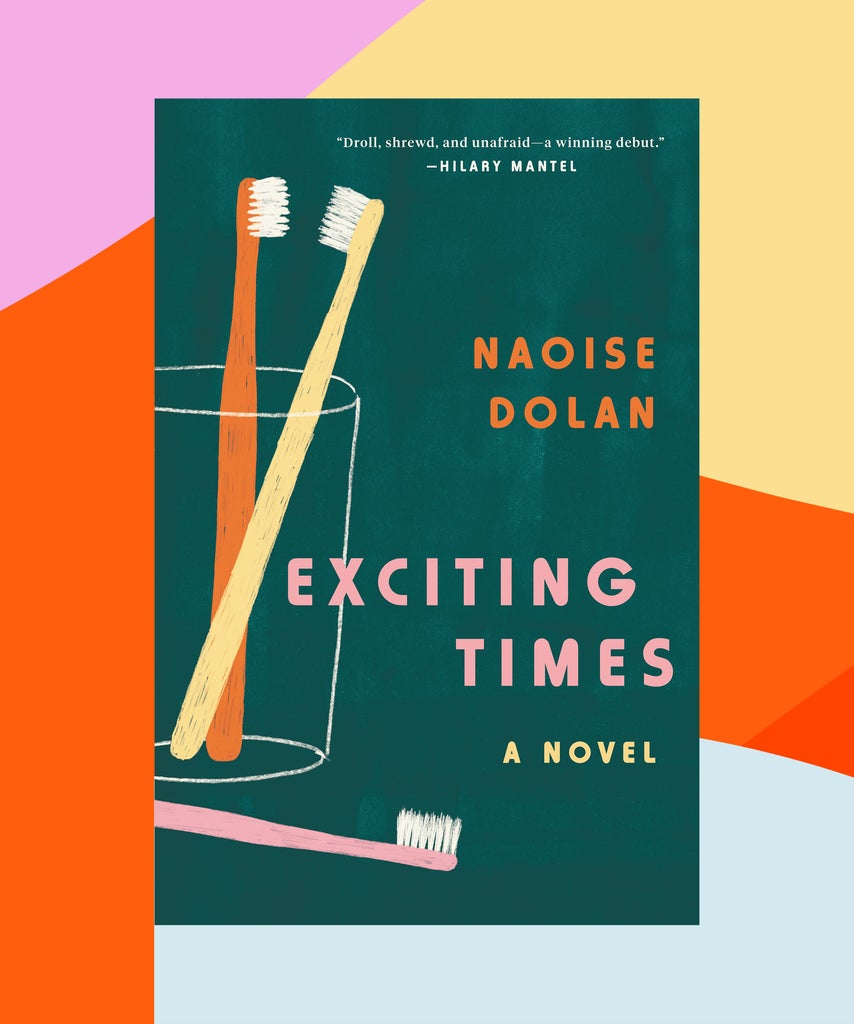

If you haven’t picked up Exciting Times already, this weekend may be the time to dive in. It’s the debut novel of Naoise Dolan, where 22-year-old Ava cashes out her “abortion fund” to move from Ireland to Hong Kong and she begins a tryst with Julian, a mysterious banker. Things get more complicated from there. Through Ava’s eyes, benefited by Dolan’s sharp prose, the readers are given a window into a thoroughly modern perspective on age-old themes of love, class dynamics, and ambition.

At the start of October, I moved my things to Julian’s. I told him I didn’t have time to go around viewing places. He said I could stay until I did.

“Take the guest room,” he said. “I get calls at night.” We kept having sex.

In mid-October Typhoon Haima came, the last of the season. We were trapped indoors until the Hong Kong Observatory gave the all-clear. Julian wore an unavoidably air-quoted “casual jumper.” He called many things casual and kept them in air quotes.

I asked why we’d taken so long to hook up. “I didn’t want to impose,” he said.

The answer I’d been hoping for was that I made him nervous. I hadn’t thought he’d had the power to “impose,” and was startled that he’d felt he had.

His sheets were very white. I once left a blot he called a wine stain, either euphemistically or because he could more readily picture me sipping Merlot than menstruating. His interest in making me come felt sinister at first, which revealed to me my assumption that if he wanted something it would probably harm me. He liked when I bit him but you had to pick your moment and I sometimes thought: there are many things I will never become expert in and I chose this — which did not suggest to me that mine was an internal monologue one would select if one could.

I researched the science of biting, learned it would still hurt him later, and knew exactly how I felt about that information.

I wasn’t good at most things but I was good at men, and Julian was the richest man I’d ever been good at.

Our wealth disparity was too wide to make me uncomfortable. It was a clownish level of difference that I could regard only with amusement. I also felt it absolved me of any need to probe the gendered implications of letting him pay for everything, which was just as well when I couldn’t afford for it to be otherwise. If something cost one percent of his income or ten percent of mine, why shouldn’t he take care of it?

I googled the salary range for junior vice presidents at his bank: €137,000 to €217,000 a year, plus bonus and housing allowance. I tried to take heart from this. That he could have that many zeroes and not consider himself wealthy surely showed that material lucre would not make me happy, ergo that I needn’t find a real job. But if money wouldn’t improve my life, I couldn’t think of anything likelier to.

I liked imagining Julian had a wife back in England. I am a jezebel, I’d think. This wine rack was a wedding gift and I am using it to store Jack Daniel’s because I have terrible taste in everything. She is Catholic — in the English recusant aristocrat sense, not the Irish poverty sense — and will never grant him a divorce, and I cannot in any case usurp her as the woman who loved him before life and investment banking strangled him, creatively.

I asked about the wine rack and he said it came with the flat.

I wished Julian were married. It would make me a powerful person who could ruin his life. It would also provide an acceptable reason he did not want us to get too close. The more plausible reading was that he was single and that while I could on occasion discharge the rocket science of making him want to fuck me, he did not want to be my boyfriend. That hurt my ego. I wanted other people to care more about me than I did about them.

As things really stood, I performed petty tasks in exchange for access to him. He jokingly asked me to organise his bookshelf, and when I actually did, he said I was brilliant. One weekend I made the mistake of pointing out that he should pack for Seoul, and thereafter he expected me to remind him whenever he went on a business trip.

“You’re so lazy,” I said. “It’d be easier to do it myself than make you do it.”

“Knock yourself out,” Julian said, which wasn’t the response I’d been trying to elicit, but I thought it could be fun, like kitting out a Barbie doll for an improbable profession. His clothes all looked the same and he kept a toothbrush and shaving things in a travel bag. I didn’t include condoms, not because I minded his seeing other people but because I was afraid it would seem passive-aggressive.

I wondered when he spoke to his parents. He alluded to conversations with his mum, but I never heard them talking. Eventually I asked.

“There’s a routine,” he said. “Every few days, she calls on my lunch break.”

“What time is that in England?” “Six a.m., but she’s up. She gardens.”

“What about your dad?”

“Hadn’t I told you? He’s here.”

“In Hong Kong?”

“He’s a history lecturer at HKU. They divorced when I was ten.” This had only emerged four months into our acquaintance. I wondered what other information he’d been squirreling away, and — God loves a trier — if some of it mightn’t be spousal.

“How often do you see your dad?” I said.

“A few times a year. When we manage.”

“Where does he live?”

“Three MTR stops away.”

“And you see him a few times a year.”

“Yes, when we manage.”

The English were strange.

Possibly to make fun of me in some obscure way, Julian remembered my parents’ names and used them often. “Have you spoken to Peggy recently?” he’d say, or: “How’s Joe?” His were called Miles and Florence. I found the comparison illuminating, but he didn’t. For Brits, class was like humility: you only had it as long as you denied it. On the escalator down the next morning I pictured his childhood home in Cambridgeshire. Tall, I thought, and empty: houses were like their owners. (I felt cruel, then decided he’d laugh. This reminded me that nothing I said could hurt him.) Although I was not someone Julian would bring to meet Florence, I imagined her having me for dinner, just the two of us. I’d mispronounce “gnocchi” and she’d avoid saying it all evening so as not to embarrass me. I would meet her eye and think: in this way I could strip you of every word you know.

I’d read that the art critic John Ruskin had been disgusted by an unspecified aspect of his wife’s body on their wedding night, which made me realise I’d always had that exact fear about anyone seeing me naked. Julian said kind things about my appearance and all I could say was “Thanks,” wishing to be cordial without implying I agreed. I’d feel his arms; wonder (a) why I was a cold and ungrateful person and (b) if anyone would ever love me; know the answers were (a) I’d decided to be and (b) no; and eventually say, “I like your arms.”

You could go manless entirely, and I saw a great deal of elegance in that approach, but enough people felt otherwise that I thought it best to have one. You had to pretend to feel sad if you’d been single too long. I hated doing that because there were other things I was actually sad about.

As with not having any man, I felt not having any sex was the decorous option — but if you were going to have it, you should have it with someone who retained a degree of objectivity. And I had to have it. Otherwise I’d never stop thinking. We both preferred me on top and I wondered if that said anything about our dynamic. I felt all your copulative leanings were meant to reveal something deep about you, and if they didn’t you had an uncompelling mind.

He wasn’t affectionate in bed, but he let me perch my arms on his chest.

“What if I were your age?” I said. He asked what I meant.

“Would you still be interested in me if I were the same person but your age?”

“How old do you think I am?”

“I don’t know,” I said, no more conscious of statistics relating to average age of first marriage than any other individual would be. “Thirty?”

“Twenty-eight,” he said. “I think I could live with your being twenty-eight as well.”

I was disappointed, and realised I’d wanted him to be into the fact that I was twenty-two. There was nothing else I had that he didn’t.

Later I googled what anyone would google. I saw twenty-nine for the UK but thirty-one in Hong Kong, reflected that neither statistic said when — or whether — men of his specific socioeconomic bracket and emotional makeup affianced themselves, and with reference to the latter surmised that he was single and did not want me to be his girlfriend. I cried about this no more than any other person would.

From Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan. Copyright 2020 Naoise Dolan. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

COVID-19 Means I’ve Lost A Crucial Year Of Dating