Director Jennie Livingston refers to her documentary Paris Is Burning as her “old girlfriend,” a long-term relationship that has lasted to its 30th anniversary, becoming in that time a cultural touchstone of LGBTQ+ cinema that introduced the world to vogueing, realness, and extravagant balls. It was shot mostly over a five-week period in 1987; Reagan was president, and New York City was marked by intensifying income inequality, societal devastation from the AIDS pandemic, and the stigmatisation of and rampant violence against the Queer community.

Following a re-release through the Criterion Collection this past February, its preservation in the National Film Archive by the Library of Congress, and its many influences on modern LGBTQ+ media, Paris Is Burning has established itself as one of the important documentaries in American cinema, having captured social issues we only now have the moral courage to talk about.

“The ‘80s were a time of greed, savage inequality, and a willingness to ignore that, and that’s a period we are in now,” Livingston said, talking about the social conditions for LGBTQ+ people when the film was shot. “There was an economic boom, but there was a lot of poverty and struggle. The AIDS crisis was ascendant in the gay community, and that certainly affected trans people too. It was a time in the community when people of a certain generation were dying en masse.”

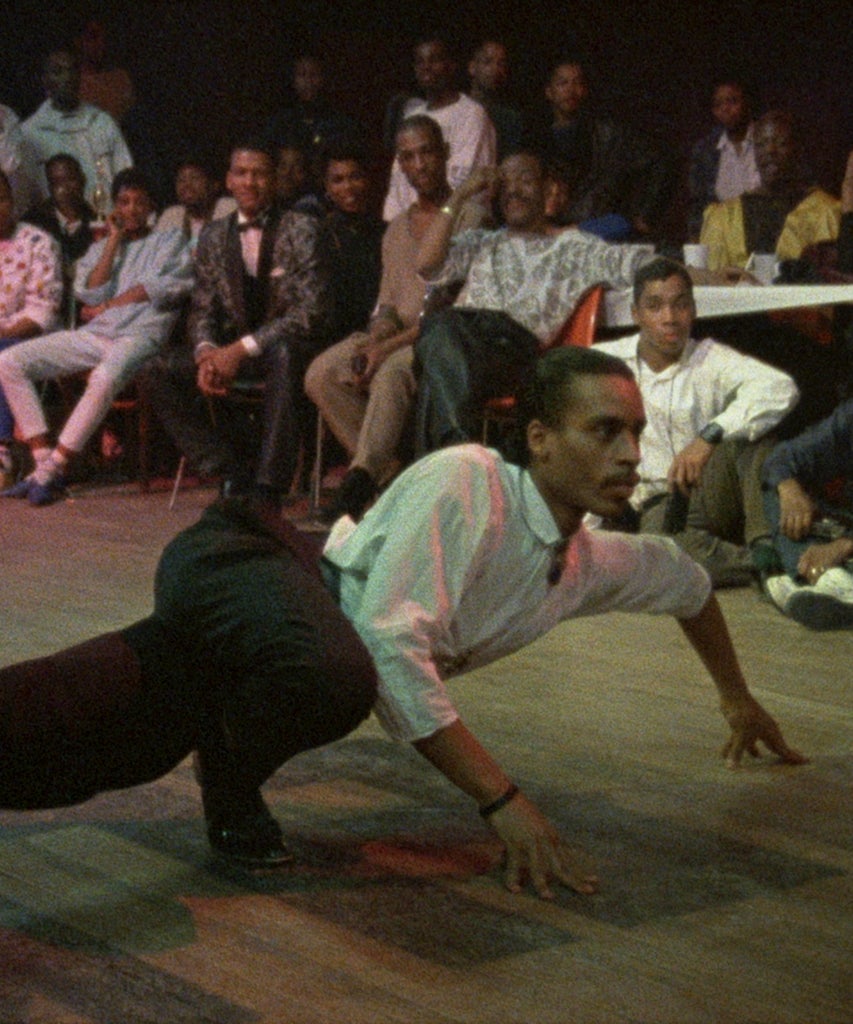

Public spaces in New York City have always been places where people go to express themselves. In the ‘80s, parks were a communal stage for voguers, and the piers near the West Village were a place for Queer people to gather with their chosen families.

“When I first discovered I was gay, I was very young; I remember walking down to the West Side, the Village, and discovering this whole world of people, of coloured folks that were just like me,” said José Xtravaganza, choreographer and Father of the House of Xtravaganza, who appears in Paris Is Burning. “I found my tribe, as they say… to see colourful characters so comfortable in their own skin and okay in being who they were. I drew from it as an artist, as a dancer.”

Livingston was struck with a similar impression. “I was a young photographer, and I happened to meet some voguers in a [Washington Square] Park,” she said. “They said if you want to know vogueing, reach out to Willie Ninja. He was thought of as a star voguer, and [I was told] you have to go to a ball if you want to see this. I went to a ball, and then I went to many other balls. It was that culture of New York — that public space — that was one of the best parts of the city.”

Livingston, who is currently working on her next feature Earth Camp One, didn’t go to film school, but, in 1985, she took a summer film course at NYU. Her assignment was to make a documentary. Inspired by meeting voguers in the park, she used the school’s wind-up black-and-white reversal 16mm camera — and took along a friend to do the sound — to capture a ball.

“This was at the [LGBTQ] Community Center on 13th street,” she said. “The one person who was there that I met was Venus; she was there with her biological grandmother competing, and I just remember having my mind blown. I had never seen any kind of cultural manifestation where genders were being questioned — the energy of it, the categories, which, at the time, I didn’t understand most of what was going on. But I understood that not all the women were biological women. I understood that the categories were commenting on how we construct identity. And as a young Queer person, and as a new New Yorker, and certainly as a photographer who loved human creation, I was blown away.”

“Creatively, what was put into whatever category you were walking, you would plan for weeks at a time,” Xtravaganza said. “You would plan every detail. It was so important because this was all we had. These categories were thought out. A lot of preparation went into it because it was so competitive, you always wanted to bring that wow factor to outdo your competitor.”

Livingston was just 24 when she started working on Paris in 1986, and spent four years working on it. She began by using a still camera to take pictures and a professional cassette recorder to record audio interviews, getting to know the culture and people in the scene. Soon enough, she decided to make a feature. She raised money by selling her car and borrowing $5,000 from her aunt to buy equipment to shoot one ball. Then, she used that footage as a fundraiser trailer to help sell the idea to a producer. “People were like, ‘No no no, don’t want to fund it, don’t want to fund it.’ They all had different reasons why,” she said.

Eventually, the late Jonathan Oppenheim, a friend (and future editor of Paris) who worked as an intern at WNYC at the time, helped her find the producer she needed. After the footage made its way to Madison D. Lacy, director and producer for the civil rights documentary, Eyes on the Prize, he invited Livingston in for a meeting, before offering to help produce.

Livingston named the film after the ball event of the same name organized by Paris Dupree. For a film that shows lavish balls crowded with shouting onlookers and confronts issues of race, class, homophobia, and transphobia, it’s surprisingly intimate. We witness quiet moments. We see the personal spaces of voguers. We hear about their lives, their dreams, their struggles; we’re conscious of their heartbeats and pride when they walk to categories with realness.

“When you can pass the untrained eye or even the trained eye, and not give away the fact you’re gay, that’s when it’s real,” Dorian Corey says in Paris, talking steadily to the camera while putting on makeup. “The idea of realness is to look as much as possible like your straight counterpart. It’s not a takeoff or satire. No, it’s actually being able to be this woman.”

“I want a car, I want to be with the man I love, I want a nice home away from New York up in the Peekskills or maybe in Florida, somewhere where nobody knows me,” Venus Xtravaganza says to the camera, lying on her bed, next to her stuffed animals. “I want my sex change. I want to get married in church, in white. I want to be a complete woman, and I want to be a professional model behind cameras in the high fashion world.”

“There are some who think we are sick, some who think we are crazy, and some who think we’re the most gorgeous special things on Earth,” she says, in a soft voice.

Venus, who worked as an escort, was strangled to death in a hotel room during filming. She was 23. “I always said to her, Venus, you take too many chances you’re too wild with people in the streets, something’s going to happen to you,” House Mother Angie Xtravagaza said in the film, reacting to Venus’s death. “We used to get dressed together, call each other and say what we were going to wear, she was like my right hand. Any time I go anywhere I miss her. But that’s part of life. That’s part of being a transsexual in New York City and surviving.” Angie would die of AIDS in 1993, three years after the film’s release. She was 28.

Time has added to the film’s significance. Many of the voguers portrayed have since died of AIDS, while some were victims of violence and other causes, exemplifying the lack of access to health care, entrenched marginalisation, and struggle to survive for people of colour in the gay and trans community that persists today. Although acts of violence are invisible in the film, they permeate the stories told by the voguers, putting faces to the issue of trans-violence at a time when that conversation was otherwise non-existent.

“It was beyond my ability to imagine,” Livingston said about Venus’s death. “I was a young person. I certainly understood the risks of being a sex worker — she talked about it. It was hard to understand, it was hard to feel the reality of it, because it just didn’t seem that someone who was so vital and so powerful could [have that] happen [to her]. She was such a strong person.”

“This phase of going back to look at footage I hadn’t seen in 30 years, and reconnecting to people from that time,” Livingston said. “I celebrate the film and I’m proud of it, but there is a lot of sadness. I want everyone to be here — Dorian, Willie, Angie, Venus — I want them all to be here.”

Three decades later, important pieces of pop culture, from Pose to RuPaul’s Drag Race to HBO’s Legendary, trace their lineage to Paris Is Burning. The documentary has influenced a generation of LGBTQ+ actors, directors, writers, queens, and creators of colour, telling the story of the ball scene, and popularising drag to a mainstream audience. Yet the film is treated as somewhat of a skeleton in the closet, with critics like bell hooks calling it inherently exploitative due to Livingston being a white documentarian who entered and captured a culture that is Black and Hispanic.

“For me to see her down there with a video camera filming, it was a bit intimidating and scary, because a lot of these kids weren’t accepted for being gay which is why this whole movement started,” said Xtravaganza, on interacting with Livingston when she was filming. “She definitely was a tough girl going into that culture because it can be shady and it can be hard, especially for a white woman at that time. I know she still gets a lot of flack from the community where some are unhappy because they feel she didn’t put them in the film or they didn’t get the accolades from it financially or whatever the stories have been throughout the years.”

“I think there’s a shift [now] in that there’s more opportunity to portray people,” Livingston said. “[Disclosure: Trans Lives on the Screen] talks about how trans people are portrayed in Hollywood. There’s, of course, Pose and Orange Is the New Black. There are people who are being empowered to make work. I don’t think there is enough. I don’t feel like we’re yet at the point where there’s fully a sense that if there’s a gay or lesbian or bi or trans or queer story that the filmmaker needs to be queer. We see our lives best.”

“I know there are people who feel like, well then, how can you make Paris Is Burning?” she said. “There wasn’t anyone else who wanted to make that film, I did have the relationships, and the people did want the film made. To this day, the stats are 96% of films in general release are directed by men. The stats for films about people of colour by people of colour are bad. I think when you have more executives who can understand in an embodied way that people need and want to see those stories, more of these films will get funded.”

Paris captured moments that looked beyond the confines of stereotypes, transition narratives, and sobering news reports that usually make up depictions of transgender lives. The voguers left a legacy of unapologetic expression and fragile humanity, creating a landmark work of art that helps gay and trans people understand their self-worth and transcend their identity to tear down the social barriers placed around them. Their names are now in the voices of many.

“We barely had rights, never mind the trans community. I never imagined it being so part of society as it is now,” José Xtravaganza said. “A lot of these people in the film don’t have the luxury of being alive today to share in the success and phenomena that vogueing and ballroom culture has become. They are to be praised, and I’m proud I witnessed it firsthand, to know the people who opened the doors. None of this would have happened if Jennie had not done such a beautiful, heartfelt documentary.”

“They have a lot to say to how we as humans live,” Livingston said. “The ball world has a lot to say [about] how we build our society, and how we have creativity and resilience in a world where it would like to knock that out of us, particularly as Queer people. There isn’t a single person who doesn’t feel like they’re up against some bad circumstances that they had to overcome to become themselves.”

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Honest Conversations With Trans Kids