I grew up in Mexico, in the northern state of Tamaulipas, until I was 12 years old. Although I was born in Houston, Texas, it was important to my parents that I learn Spanish, which is why they moved us back to Mexico. They also wanted me to connect with our Mexican culture, including El Día de Muertos: the day we honour those who have passed and are now in the afterlife.

From October 31 to November 2, altars, also known as ofrendas (offerings), are placed everywhere to honour those who are no longer with us. Our family, friends, and loved ones who have passed away get a special place on the altar with photos, flowers, and their favourite foods and drinks. According to the tradition, which has been around since before colonisation, their souls come back to say hello and enjoy the offerings left for them for two days.

It might sound like El Día de Muertos is a celebratory holiday altogether, and that’s why people travel to Mexico to partake in the festivities. Influencers and makeup artists paint their faces in the style of the Catrina — the elegant skull female figure — as a costume without knowing the symbolism behind it. Yes, it’s a holiday filled with vibrant colours and details, but every single one of them holds profound meaning — from the photos and stories shared to the cempasúchil (Mexican marigold) flowers on the altars, which are selected because their orange colour is supposed to guide our loved ones from their world into ours. The significance behind the altars, ofrendas, and flowers is deeper than it seems — and it’s one that begins with grief.

I did not know what grief was for a very long time. However, at a young age, I understood that people who were once a part of my life would one day suddenly be gone. My grandfather passed away when I was four years old. He was strong and full of life. When we went over to his house, he had a special corner in his closet filled with candy just for me that he called my tiendita (little shop). When the time came, I don’t remember being told my grandpa had passed away. When you’re young, your parents might have trouble finding the right words to explain why, all of a sudden, someone is gone — but as I grew older, I came to understand. I realised my grandfather was no longer available for Sunday barbacoa (our family tradition of eating meat slow-roasted over an open fire), and we stopped visiting his home during the holidays or weekdays. A little before his house was sold, I spent time there missing my grandpa’s presence. His memories lingered, but I knew he would never come back to me physically.

As I matured and gained a better understanding of death, I visited my grandpa’s grave in the cemetery with my grandma and mom. Every once in awhile, my parents would go to the church where my paternal grandparents’ remains were laid to rest. I would touch the outside of the urns and grave stones with my fingers, trying to remember what it felt like to be around my grandparents. Now, I yearn to have had more time with them. It’s extremely important to me to keep their memory alive, which is what El Día de Muertos is all about: making something sad and melancholy and turning it into a respectful celebration.

My parents never talked about their grief to me; it might have been difficult for them to explain. However, a few years ago, I experienced it firsthand. My father’s best friend, who I called my uncle, passed away in his sleep in October of 2016. We were supposed to have lunch with him that day. The day before, he had been feeling sick and asked my dad to bring over Gatorade for his stomach ache. The next day, when I got home from school, my dad asked me to go with him to see if my uncle was home since he had not returned his calls — and that’s when we found him.

My uncle was like a second father to me. Just like my grandpa, he was filled with laughter and knew how to have a good time. My dad and I spent every SuperBowl and almost every Christmas and New Year’s Eve with him since we moved to Texas. He lived by himself, which is why no one could have known he was in pain.

I watched my parents cry for him for days — and I did, too. I had a voicemail from him on my cell phone that I listened to over and over again for days until I fell asleep. It made me feel as if he was still in my world. I was afraid his passing would be too much for my dad, but one night we cried together and hugged. To me, the grief I experienced was short as I came to understand that maybe it had just been his time. But it was necessary for me to shed the tears and to listen to his voice one last time. Memories are what allowed me to no longer feel sad, but remember him in a more positive light.

The passing of my uncle was something I had never experienced before. He and I got to spend more time together than I ever did with my grandfather. It was also very unexpected, which made it difficult to process. However, my parents and I dealt with our grief together, which is something I am thankful for. My dad isn’t afraid to express his feelings, and that made us stronger during such a difficult time. My uncle now lives permanently in our living room and so do his old shot glasses. For both of those important men in my life — my grandfather and uncle — we place drinks and tamales as offerings on our alters for them.

Mexicans are known for turning sadness into a celebration — not to make it less important, but to rejoice in memories instead. With COVID-19, many of my friends have lost important people in their lives. Without the proper chance to say goodbye, they had to let go. Nonetheless, we turn on music during this Día de Muertos, and families who might have never been united are strengthening ties because of their losses. That’s what makes this celebration beautiful: the unity it represents.

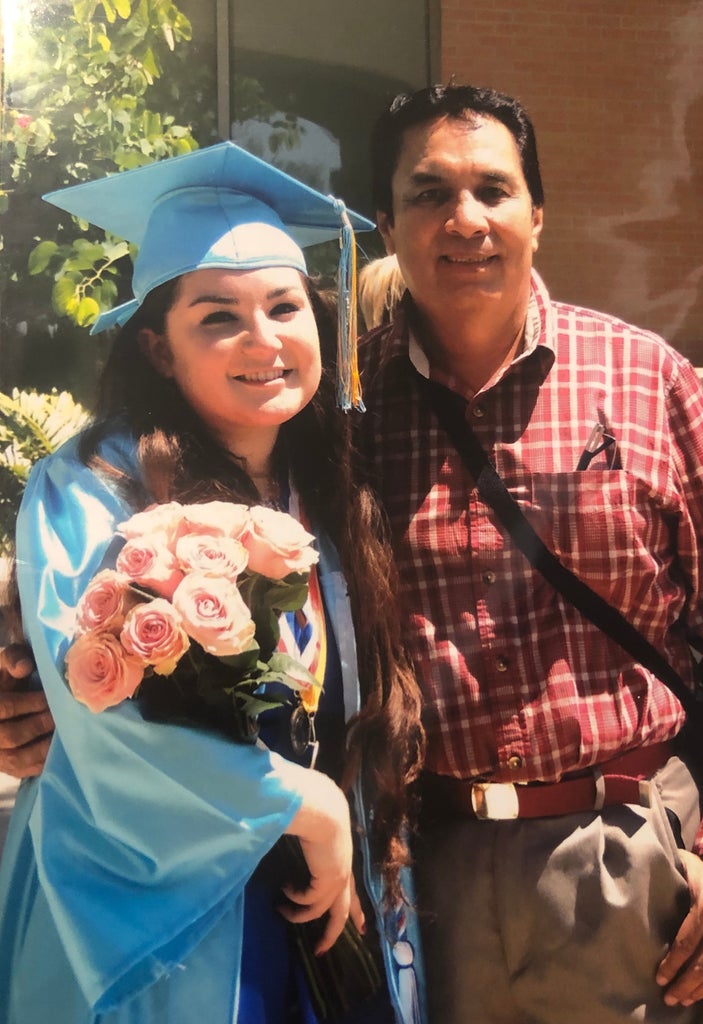

El Día de Muertos, a tradition from pre-hispanic times that has transcended into today’s beautiful commemoration, is about making sure that people are not forgotten and still remain present in our lives. It’s possible that my grandparents and my uncle have been around me to see the woman I have become. And with that, I’m thankful to be a part of a culture where death can be seen as a transformation of grief — a beautiful tradition created to keep those who passed on alive in our hearts.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?