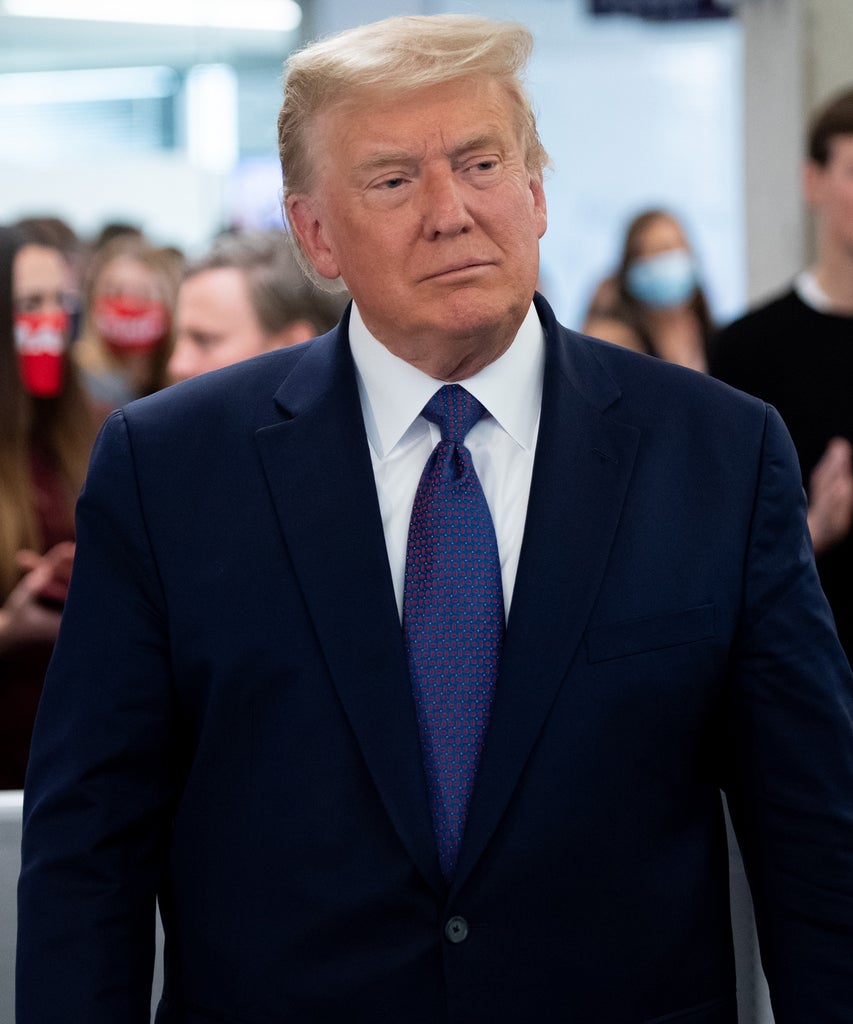

Donald Trump’s presidency is finally coming to an end. But one important question — other than whether Trump can run again in 2024 — is whether he is allowed to pardon himself from the litany of legal investigations and civil suits he faces upon leaving office. In case you need a reminder, Trump is currently under investigation for insurance fraud, criminal tax evasion, grand larceny, and a scheme to defraud. He is also still being sued by writer E. Jean Carroll for rape.

In part, many believe that Trump’s disproven claims of election fraud are just a ploy to run the clock that will eventually land him behind bars. So the question is, what kind of power does the president really have to pardon himself? According to Article II of the Constitution, a sitting president “shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” That may sound like we have already answered the question; however, therein lies a small yet important technicality within that phrase that requires some unpacking. The operative word? Grant.

Because of this, we are actually asking the wrong question: It’s not about whether Trump can pardon himself, but whether he can grant himself a pardon. This may sound like the exact same question but bear with us. According to context clues from the text of the Constitution and the word’s meaning at the time it was written, the answer is no. He cannot pardon himself. The president only has the power to grant pardons. For context, the same word appears multiple times in various clauses of the Constitution. Every time the word appears, “grant” is a transmissive term meaning it is from one entity to another, reports The Atlantic. It is not used reflexively as in “to grant oneself” a pardon — it is always used interpersonally.

Comparing a word to its uses in other instances within a historical or legal document is a common technique used by judges and legal scholars to surmise the intended meaning in context. If a court were to base its judgment solely on the context of the word in the Constitution, it would be reasonable to determine that the president cannot, in fact, grant himself a pardon.

But it probably wouldn’t be that simple. One of the most common legal interpretive methods, promoted by Justice Antonin Scalia and popularised among conservatives, is to look for a term’s “original public meaning.” This would involve looking at how everyday English speakers in the late 1700s would have understood the word should they have read it in a legal document.

To get an answer, one would have to look through legal dictionaries of the time. The most popular legal dictionary at the end of the 18th century was The Law-Dictionary: Explaining the Rise, Progress, and Present State of the English Law; Defining and Interpreting the Terms or Words of Art; and Comprising Copious Information on the Subjects of Law, Trade, and Government (give us a second to catch our breath). In it, the word grant has the singular definition of meaning “a deed which passes or conveys land from one man to another.” (Zoom in on “to another.”) Nowhere in that dictionary does it say that a person could grant something to themselves. Furthermore, the idea of a reflexive use of the term reportedly didn’t exist in popular language at the time.

So based on context clues from the original document, legal dictionaries in use at the time, and the development of the English language in the last few centuries, the seemingly inconsequential word “grant” might have just kept us away from an even more complicated end to Trump’s presidency.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Will Trump Go To Jail After The White House?