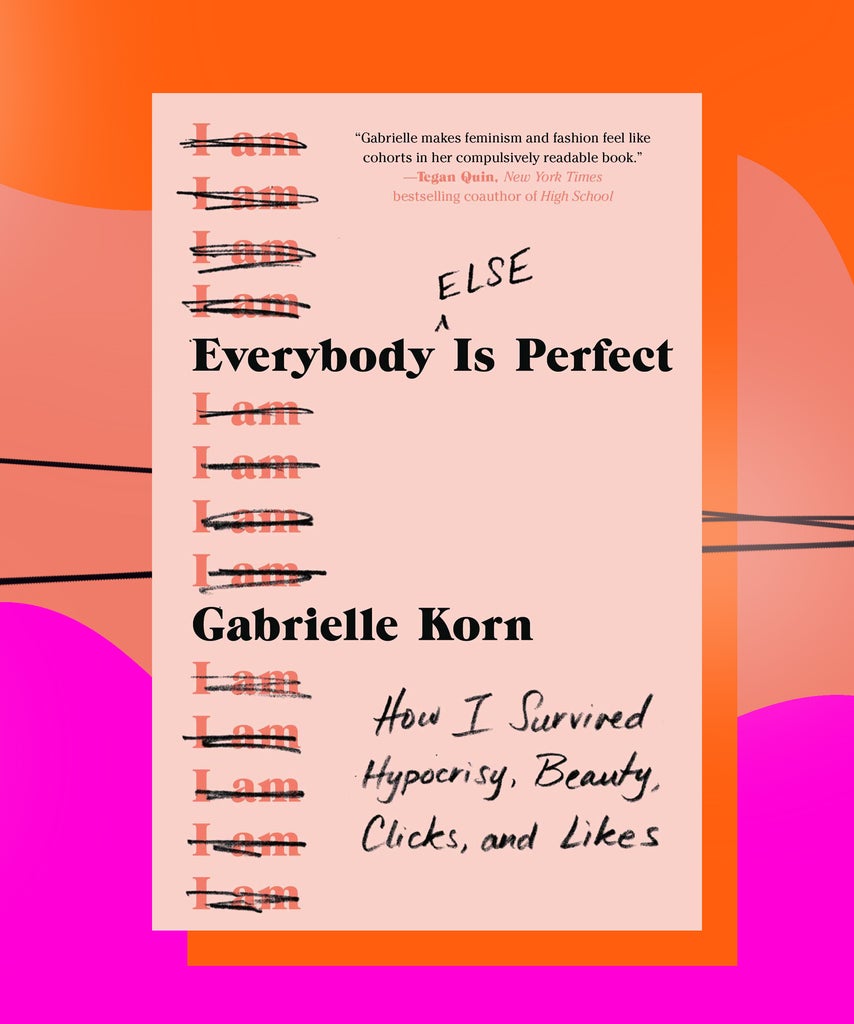

Gabrielle Korn has always had a knack for asking the most incisive questions. This was true during her two stints at Refinery29, where she was most recently — until August 2020 — our (beloved) director of fashion and culture. It was also true when she was editor-in-chief at NYLON, where she was the youngest and first queer woman to hold the position. And now it’s true in her new book Everybody (Else) Is Perfect: How I Survived Hypocrisy, Beauty, Clicks, and Likes.

In the memoir, Korn uses her own personal and professional experiences to highlight and comment on the many hypocrisies that exist in women’s media, which often positions itself as “woke” while continuing to uphold belief systems that work against the people they claim to want to uplift.

Korn’s essays are intensely personal, and she never hesitates to explore those uncomfortable moments that all too often remain unspoken. The following excerpt was adapted from a chapter in which she discusses her anorexia and grapples with the question: Can I be a “good feminist” and have an eating disorder? — Molly Longman

It was June 2017, a precious time of year in New York City when the heat has yet to vaporise the garbage juice, so the air still smells like pollen and possibility.

I was on a third date with Wallace, a friend who had recently admitted to sharing the crush I’d had on her since we met a few years earlier. Because we’d been casual friends for so many years before, we’d quickly fallen into tell-each-other-everything territory, and I was going full speed ahead, divulging all the gory details of a breakup with a woman I’d been with for a year.

Maybe it’s because I’d had two negronis, but I then found myself admitting a detail to Wallace that I had only recently begun to say out loud: “It got complicated because I had taken a little break from food.” I said it casually, like I was kind of joking, not wanting to sound dramatic.

Everyone else so far had regarded this admission with alarm, which was annoying, or skepticism, which was more annoying. Wallace, though, matched my tone. “Oh yeah?” she said. “That’s no good. You kind of need food.”

“Yeah,” I laughed, relieved. “As it turns out, you really do need to eat things.”

No one really knew: I was about three months into recovery from what I was told was anorexia.

It’s estimated that between 1.25 and 3.4 million people in the UK have an eating disorder. Meanwhile, it’s also estimated that more than 70 percent of them won’t seek treatment because of stigma. This statistic feels especially prescient: In this golden age of female empowerment, we aren’t supposed to have eating disorders anymore. It’s not cool to hate your body. Women, and especially women within the public eye, are obligated to promote a message of self-love, to put all our cellulite and wrinkles and rolls out there proudly. Culturally, we’re all about “wellness” and redefining it on our own terms. And yet, studies show that eating disorder rates continue to rise.

I’ve moved in and out of periods of disordered eating for as long as I can remember, though I can never tell it’s happening until I’m on the other side. When you admit to having an eating disorder, you’re also admitting that you’re body negative in an aggressively body-positive world. You’ve prioritised impossible beauty standards over your own health. And ultimately — despite your feminist politics — you’ve internalised the patriarchy. The misogyny that says women need to be skinny has infiltrated your brain until you believe it, until it feels like it’s a belief system you organically hold. It’s oppression at its most sinister: so pervasive that it becomes part of you. By starving yourself, or making yourself throw up, or otherwise doing whatever you can to keep your body small, you are in effect working to uphold the values of a system built on keeping you down.

That is, at least, what I told myself, what I punished myself with, and what many others do, too; I think it’s probably why many people don’t want to talk about their eating disorders in today’s world, which can feel built on surface-level feminism depending on what bubble you live in. For me, saying it out loud was nothing short of devastating, especially because a huge part of my mission had been to help young women expunge patriarchy both from their own minds and their communities.

It felt like admitting weakness: I was trying so hard to be the picture-perfect empowered millennial woman, but I had gotten stuck on the “picture perfect” part.

In our newly woke world of marketing based on “positivity,” the blame is once again placed on women — but this time, it’s not our bodies that are wrong; it’s our feelings about our bodies. And my feelings about my body were definitely wrong, creating a vortex of shame.

I’d been in therapy for years without bringing up my on-again, off-again eating habits. I didn’t want to tell my therapist about it, because I didn’t want to stop — I liked having that kind of control over my body. I also didn’t really think it was that big of a deal. When I finally told her, she was alarmed, and convinced me to see a doctor so we could determine how severe it was based on test results. She sent me to a physician who specialised in eating disorders in adolescent girls. The day before I went, I wondered if I should eat more so that she wouldn’t think I had a problem, or if I should eat less so that she would take me seriously. I went alone, not wanting to burden anyone with what felt like a self-imposed disaster.

The doctor diagnosed me with anorexia quickly. I was mortified but also relieved; I was exhausted from being hungry all the time, and now there was a professional telling me I needed to eat more, or else. There was also something so soothing about having someone tell me what I had to do — I had been making my whole life up as I went, including how I took care of myself, and she lifted the burden. There were, in fact, rules to follow in order to stay alive; I actually couldn’t just go without eating indefinitely.

Years of therapy have clarified for me the connection between my relationship to food and my coping mechanisms, or rather my lack thereof. Being skinny was a weapon, a strategy, a safety net. Trying to lose weight was a convenient way to distract myself from what was really going on.

It was, maybe most importantly, a secret so easy to deny because there was so much evidence to the contrary: my work, for one. Being gay came in a close second. Queer people are so inclusive, so all about supporting all kinds of bodies— right? Socially, I was part of a world where fatness had been reclaimed. Queer fat femmes and butches were lavished with as much positive attention as everyone else. They were celebrated. And I celebrated them, too. I just didn’t think my own body could be included.

After a round of blood tests on that first visit, the doctor called me and said that I needed to change my lifestyle in order to not do permanent damage to my body. All my results were low; my estradiol was so minimal that I was barely getting my period. She also explained that based on how low my T3, or triiodothyronine, levels were, it would take a full two years for my brain to fully recover. T3, she told me, comes from good fats and lines your brain; it makes your synapses connect. Low T3 is a symptom of starvation. It’s why it’s hard to think when you’re hungry. This was the first piece of scare-tactic information that truly got to me. I drew the line at a decline in mental capacity.

The doctor told me the good news was I’d be able to recover fully as long as I started eating again. Eventually, I did, slowly at first, working with a nutritionist to get back up to three meals a day, then adding snacks, then making sure that every meal was well-rounded and satisfying.

The doctor didn’t take health insurance, and my plan didn’t cover my diagnosis in the acceptable out-of-network expenses, so my first visit was $800, my follow-up was $400, and my third visit was another $800; the nutritionist was $150/week, as was my therapist. I couldn’t afford both regular doctor visits and the weekly therapist and nutritionist, which was extra motivation to follow the plan they created for me: I hated the thought that my hard-earned salary was all going to treatment. It felt like failure. So I stopped seeing the eating disorder doctor after three visits and stuck with the therapist and nutritionist. I had to relearn how to put meals together, which was humiliating but also incredibly helpful. I surrendered completely to professional care, understanding that my own ideas about health and food were no longer trustworthy.

After outsourcing all my various issues to professionals around Manhattan, I managed to finally feel like I wasn’t living from crisis to crisis; I could approach food as something I needed to feel good, not the other way around.

It’s not hard to imagine why women might hate their bodies when our place in the world is so often determined by them, and when so few people actually occupy that highly glorified yet rarely lived place of ultra-thin/straight/white/cisgender privilege. Despite being the majority, plus-size women are discriminated against and often publicly shamed for their appearance, which affects everything from access to effective healthcare to employment to travel to shopping. But thin women, in my experience, balk at admitting to being a privileged category, especially thin white women. I wonder if it’s because they’re punishing themselves so much to maintain that skinniness that the suffering feels louder than any societal benefit they encounter. But that’s a pretty naive way to experience the world, indicative of a privilege so ingrained you hardly realise it’s there. It also seems entirely possible that the panic to remain thin stems from a fear of losing that privilege — a maybe subconscious admittance.

A so-called good feminist in today’s world thinks that bodies in their natural state — cellulite, rolls, stretch marks, and all — are perfect. It’s almost like someone forgot to tell us to include ourselves. Or maybe we’re so used to hating the things that we’re suddenly supposed to celebrate that it’s simply easier to start with everyone else.

Copyright 2021 by Gabrielle Korn. From Everybody (Else) Is Perfect: How I Survived Hypocrisy, Beauty, Clicks, and Likes by Gabrielle Korn, published by Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Adapted and printed by permission.

If you are struggling with an eating disorder, please call Beat on 0808 801 0677. Support and information is available 365 days a year.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Did The Racial Trauma of 2020 F*ck With Your Body?