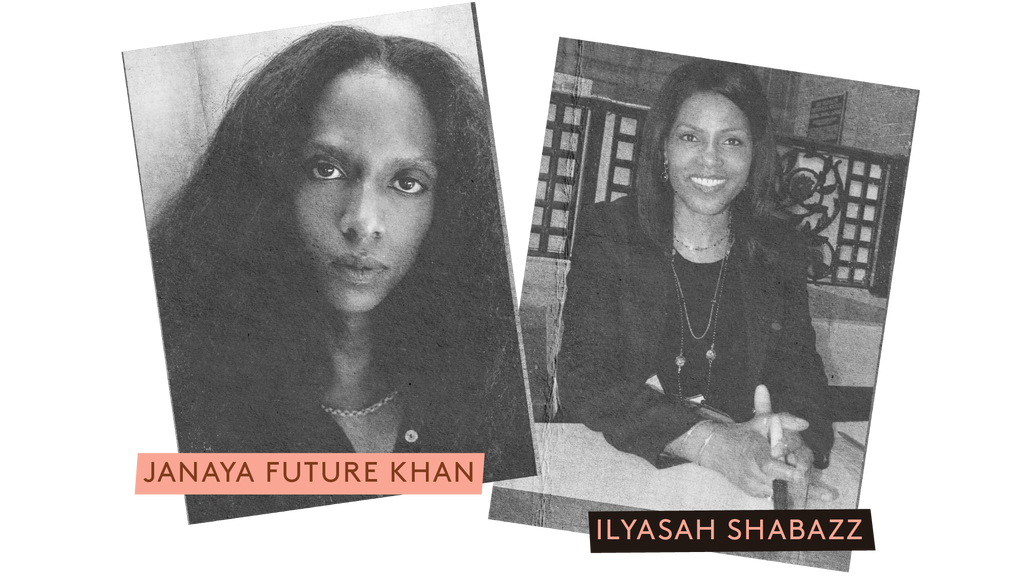

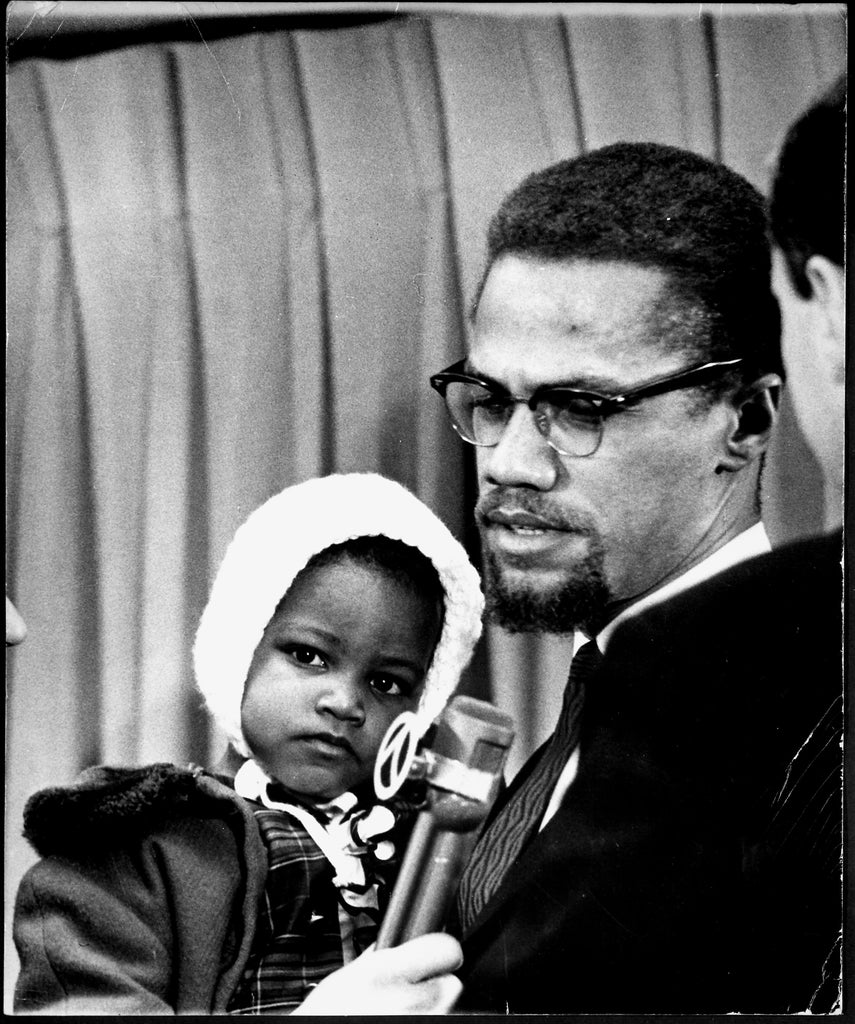

Nearly three decades separate activists Janaya Future Khan and Ilyasah Shabazz, but they are bonded by the same goal: Black liberation. Shabazz was just a toddler when her father, civil rights icon Malcolm X, was assassinated in 1965 (in the presence of Shabazz, her pregnant mother and three of her sisters). She’s since devoted her life as an educator, motivational speaker, and author to preserving her father’s legacy.

It’s a legacy that has inspired Khan at every step of their work with Black Lives Matter (they are one of the faces of the movement internationally and a co-founder of the Canadian chapter), and though his death came years before Khan was born, it’s undeniable that Malcolm X’s spirit lives on through the work of the charismatic, outspoken leader. Khan’s “Sunday Sermons” Instagram series has been hailed by Vogue as “the place where political action and spiritual liberation meet.” Every week, the Toronto-born, LA-based organiser tackles topics you could imagine Malcolm X approaching with the same fervour, reverence and urgency if he was an activist with an Instagram account in 2021.

Over Zoom from her New York home, Shabazz states that her father is quoted “53,7000 times per hour on social media,” and it doesn’t come as a shock to Khan, who has “poured over every page” of X’s autobiography and has quoted the trailblazer themself. As a queer, gender-nonconforming social-justice educator and millennial, Khan may seem to stand in stark contrast to Shabazz, an adjunct professor of the Baby boomer generation, but their rapport comes easy and is clearly based on a mutual respect and admiration.

While listening to Khan and Shabazz speak, it’s hard not to think of the unfortunate parallels between the two movements — the civil rights era and Black Lives Matter — and how much work there still is to be done. If you pay attention to Twitter, the generations are seemingly in constant opposition. This year, we’re looking back as much as we look forward in order to acknowledge that the past and future cannot exist without one another. Change is slow. Movements are long. And the fight for liberation is laborious no matter how old you are, which is why we brought these two extraordinary thought leaders together to cut through the discourse and have a real talk about progress, purpose, and finding peace in activism.

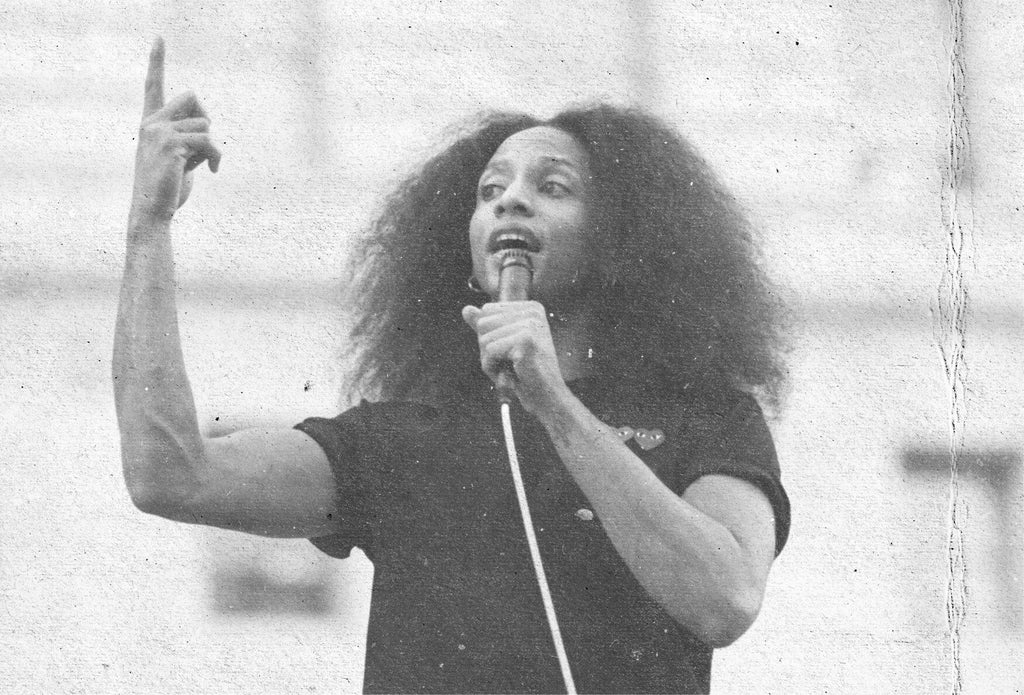

Activist Janaya ‘Future’ Khan speaks at a ‘Jackie Lacey Must Go’ protest organized by Black Lives Matter in front of the Hall Of Justice

‘Jackie Lacey Must Go’ protest, Los Angeles, USA – 30 Sep 2020

In an intimate conversation that will leave you inspired, comforted and, at times, emotional, Khan and Shabazz talk about Malcolm X’s legacy, the benefits and pitfalls of social media, and how they each stay motivated to keep fighting.

Janaya Future Khan: “I read about Malcolm X’s work. I get to have my own interpretations and create my own idea of who he was and what he meant, but I don’t have to live in the legacy or feel the weight of it. How has being his daughter shaped you as a person?”

Ilyasah Shabazz: “It is who I’ve always been. I’m so grateful to my mother [Betty Shabazz] because she was a young woman when she witnessed her husband being assassinated. A week earlier, her home had been firebombed. This was a young couple. My mother was in her late 20s. Her husband was 39 years old. They had babies, and she was pregnant. I usually look back on her life not from the perspective of a daughter, but just looking at this young sister who was partners with Malcolm X and the wife of a man who challenged the government that had been historically unjust to its own people.

I’m grateful that she raised us in a bubble of love. She made sure that we loved who we were as women, as people of the African diaspora, and as Muslims. Growing up, I never really felt the pressure because it was easy to just be me. When I went to university, people started saying, “You’re Malcolm X’s daughter.” And I’m like, Whoa, what’s that? I remember calling my oldest sister and saying, ‘What am I supposed to do?’ She said, ‘You don’t have to pass the test to be Malcolm’s daughter, you already are.’ I always translate that for other people; if you can look in the mirror and like who you are, that’s all that matters.”

JFK: “That’s right.”

IS: “I know that the Black Lives Matter movement began out of compassion, passion, and a Facebook post. What your generation has that my father didn’t have, and I didn’t have, is the ability to touch a button and communicate with people all around the world. Janaya, how have you used social media as a tool to organise all of this great work that you’re doing today?”

JFK: “Social media is tough. I don’t have an easy relationship with it. We have seen through social media the birth of mass mobilisations in quicker succession than we ever have. We went from [the] Occupy [movement], which was just the very beginning of what that mass mobilisation could look like, to Black Lives Matter, to Standing Rock, to the Women’s March, to No Muslim Ban, to Parkland and #MeToo. All of these movements have been really organised and galvanised around social media. To that, I feel energised, but what it’s also allowed for is organising on the other side in unprecedented ways. For example, the attack on the US Capitol is a result of social media.”

“While we have been able to organise ourselves in a particular way, so have far right and far right extremism with far more allowance than protesters for Black liberation have ever experienced. Social media has made life so vastly different than anything that I think we as people, as humans could have ever imagined. I think that the implications of this time on us, on our psyche, and on our organising has yet to be seen. I’m grateful for [social media]. But if I’m being 100% transparent, I’m also a little terrified of what it means for the future us.”

IS: “And what do you think it means? To me, it seems like so many young people were politicised through direct actions, protests and marches this past summer because of the global pandemic and the negligence of a failing administration. I thought that it was really a good wake up call — not that we needed the wake up call, but it seemed that so many others did. This youth movement attracted global support in 50 US states for the first time, then 18 countries abroad, where people actually got involved. I would go running in the morning and I would see these makeshift signs around my community that said ‘Black Lives Matter.’ And it was just so beautiful.”

JFK: “There were signs everywhere that said “Black Lives Matter.” It was on walls. It was on shirts. It was on signs on people’s lawns. As small as those things are, and I know a lot of pure leftists will have critiques on this, but I love it. I love it because it’s a connection. And once there’s a connection you can turn that into a commitment.”

IS: “Absolutely. It’s important to retain this generation with information. My father is quoted 53,7000 times per hour on social media. And young people are discovering whatever it was they were learning in classes was inaccurate.”

JFK: “That’s right. I, like millions of people, have read Alex Haley and your father’s collaboration on The Autobiography of Malcolm X and poured over every page. There’s a period of time that tends to be less the focus, and that’s where he’s in prison. I know that your new book [The Awakening of Malcolm X] really focuses on those adolescent years that get swept over for what he became, not how he became. Why is that period of time so important to you to capture now?”

IS: “In 2012, the US spent 81 billion taxpayer dollars (£58bn) on correction facilities. Since 1970, the incarcerated population has increased 700%, and this is what is happening to our young people. For me, it was about first recognising why Malcolm went to prison — the society in which we live and how it’s been designed — and to show that this was Malcolm at 16-years-old. He wasn’t a grown man. He was assassinated at 39. He was a very young man when he lived his life and made this long-lasting impact. I wanted to make sure that we focused on the humanity of these young people who are being incarcerated. Bryan Stevenson said, ‘We will not be judged on how we treat the rich and the celebrated. We will be judged on how we treat the poor and the incarcerated.’”

“[My father] was the head of the debate team while in this prison. He was always a smart young man, because of values instilled in him by his parents. I want to make sure young people understand that you don’t go to jail and miraculously become Malcolm X. You go to jail and become Malcolm X because of your foundation and village, and we have to fortify that village.”

JFK: “Yes, that’s right.”

IS: “I want to ask you about the discourse online about the differences between how the previous generations approach Black liberation and how young people approach the Black liberation movement. The stereotype is that young people are more radical. And that elders aren’t. So tell me, do you think this is true?”

JFK: “I’ll say this: I’m a millennial. And at this point, I don’t understand half the things that Gen Z says on social media. There are different cultural cues. Gen Z has a lot of critiques about us. Social media changes things so quickly these days so that the discourse changes and evolves. Half the time, millennials aren’t radical enough for Gen Z in the same way that we think that Boomers and Gen X-ers aren’t nearly as radical as we are. I’m less interested in who is more radical. I think it’s about picking up where the other generation left off and continuing to march forward. I think that’s exactly what we’re supposed to do. There can be frustrations that we’re not as far as we should be, but here’s the question: how much of that are we going to put on oppressed people? And how much are we going to put on the actual system that shapes what norms and the status quo are?”

“Black Lives Matter is a movement that is largely led by women and queer and trans people, and that is on purpose. There have been a lot of civil rights heads and people who came before us who said, “You’re not neat enough. You don’t dress the part. Why are you bringing sexuality and gender into things?” And there was a lot of criticism and resistance from mainstream media that desperately wanted a singular male voice that we just refused to give them. They wanted someone where they could say, “You’re the new Malcolm X. You’re the new [Nelson] Mandela. You’re the new Martin [Luther King Jr.].” Have we met people who are from what could be considered “the old guard” who have nothing but critiques without care to offer? Yes. And I know that from my generation, there’s a belief that folks in the civil rights era couldn’t tolerate queerness and couldn’t tolerate gender and sexuality. As much as I believe those things to be true, I also know that society can’t tolerate those things either and they both have to shift. I wonder if I could have been a leader at that time in the ’60s and ’70s as I am? Probably not.”

IS: “Why not?”

JFK: “I believe in my personal power. It took a long time to get here, but I do. It has to be political power, though. Martin, for example, wasn’t just someone who came about from nowhere. Martin was chosen. He was chosen by a group of very sharp, smart, sophisticated Black women who knew what the heck they were doing. They looked at his looks, his charm, and the way that he spoke. There was a whole administration in that movement that designed that. And still it was a very misogynist movement. We saw that also happen in the Black Panther Party where Black women were pushed to the side because of things like patriarchy and misogyny. And we’re not even talking about within the realm of sexuality. I know that time it would be hard and damn-near impossible for me to hold the same kind of weight today that I do now if I were in that time, because so many the systems would be conspiring against me in a way that was completely normalised and embraced, even by our movements. There was a belief that women should be left behind and that queer, LGBTQ people should be quiet.”

“I think in this generation it’s simply not possible for [queer people] to be on the side. But in terms of those philosophical shifts, have you seen major changes happen around things like gender, inclusion, and sexuality? What do you think still needs to happen?”

IS: “I know that my father said that we are not discriminated against because we’re Christians, because we’re Jewish, because we’re women, because we’re gay, or because we’re straight. We’re discriminated against because we’re Black. And I think that what happens is we somehow allow these divisive tactics to continue to prevent us from going forward. To me, it’s a distraction. When we focus as my father said on what we have in common and what the ultimate goal is — to rid this bigotry and this terroristic system that exists — we can do it. But it just seems that we keep getting distracted by all of these things that don’t matter. At the end of the day, Black power is not exclusionary. It simply says that we’re demanding our place in the human family.”

“In the 1950s when my father came onto the human rights scene and you had young people marching, demonstrating, protesting for a quality existence, Malcolm came along and said, ‘Look, we demand our human rights as your brother, we demand our human rights ordained by God.’ We’re not focusing on the things that don’t matter. If we stand around and squabble over what differences we have instead of what we have in common, we’re missing the damn boat. At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter. Because we are not accomplishing the goal that is intergenerational. It is those who precede us that make these significant accomplishments for us. We stand on their shoulders. So we have to embrace them.”

JFK: “I think there are a couple of things that you laid out there that are so important. One is the misrepresentation of Malcolm X’s stance. I can tell you personally that people have manipulated your father’s words to try to shut me up, to say that I de-legitimised the movement. And there has been a lot of rejection of Black Lives Matter from cis straight Black men. They don’t want to follow us. They think that we represent the demise of the Black family. That is what happens when we accept the conditions of a colonial imagination. When we accept these ideas as if they were our own. I think that’s what we’re fighting overall.”

“We’re fighting the idea that we’re all born into a script and there is a singular way to live, and a singular way of understanding each other, and a singular way of doing things. If we accept a couple of those conditions, you’re accepting all the other ones too. To accept that I should not exist because I’m queer or because I’m trans, it is the very same logic that says that Black people should not exist for the simple reason that they are Black.”

IS: “If anything, that is what was imposed on us. It’s the psychological scars and the post-traumatic syndrome of slavery that Dr Joy DeGruy talks about.”

JFK: “That’s right. And there is a weight that only a Black woman can know when it comes to carrying our people forward. I think of Zora Neale Hurston, and I’ll adjust language just a little bit, but she said, ‘the Negro woman is the mule of the world,’ and there are moments where I look at you and I look at Bernice King, I think of Mama Harriet [Tubman], Rosa [Parks], and Angela Davis. We look to you all constantly for answers. You are our answer. You are meant to be the moral compass of the world while you carry the entire weight of it. So, what do you do to stay afloat, to keep going, to be inspired, or just to get by?”

IS: “Having lost my father the way we did, or my mother, I’ve always been grateful for the self-love that my mother made sure that I had. And so when I first started tutoring young girls in a group home facility, I had to figure out what I was seeing. I had not been familiar with young people who didn’t love themselves. And who didn’t have that light about life. And so I always felt that we needed a better educational [system], that every child should have the opportunity to know that they’re worthy of love and that they’re worthy of a quality education. They’re worthy to participate in mainstream society in any way they desire. What keeps me going is knowing that it’s adults’ responsibility to ensure that all children have these things.”

JFK: “I was one of those group home kids. That’s where I spent high school and it was not easy. I didn’t have someone like you. It made life in moments unbearable because everything that you see in the world is telling you a story that cannot possibly make sense. It’s unfathomable for a child to reckon with the fact that they mean nothing. It fundamentally reorganises your insides and you can spend a lifetime trying to collect the pieces of you back again. If it were not for this work that we’re talking about, and the ability for me to find these histories and our people in books, which is where I found refuge, I may not be here. It took me a lot longer to find mentorship. And even still that mentorship was largely in the imagination I created from the works of people like your father. He stood in that absence.”

IS: “When I look at you, I just see just dynamism. I see greatness, and you make me feel very proud. When I look at young children, that’s what I want to give, because it’s how my mother made sure I was programmed. I’m grateful to my ancestors. There’s lots of peace here when I think of the next generation.”

“Malcolm said it would be this young generation who would recognise that those in power have misused power and that change was going to be made, and they would be willing to roll up their sleeves and make that happen. This is something that I see you doing through your work, and I’m really quite proud of it. I’m proud of you. But I’m also protective. What do you do to sustain yourself? Because I know this work is challenging.”

JFK: “I box. I miss my boxing club. That was the hardest thing. That was my therapy. I do [talk] therapy as well, and that’s helpful, but the body remembers and internalises things very differently than the mind and the spirit. Being physically active is very, very important to me. I actually have a heavy bag stuck in the concrete out back so I can just get out there and have that catharsis.”

“It’s also really about the community for me. I have been privileged enough to be able to open my mouth after years of not knowing how to, after never knowing what to say. And I’ve been privileged enough to be able to find that [voice] and to speak. And I’m lucky enough that, for whatever reason, sometimes people want to listen. I’ll never squander that. I feel like I owe a great debt to the world and I never ever want to squander a moment of it. When I feel my most melancholic and I just want to lay down on the floor and look up at the ceiling in an existential crisis, I give myself 10 minutes or so to do that. And then I remember that I still owe too much, and there’s still more work to be done.”

IS: “It always goes back to the work. That’s what matters. My father was organised and strategic as he made sure that everyone understood the ultimate goal, that what we had in common was going to keep us together. You focus on your goal and do not give energy to the things and the people that don’t matter. I look forward to having more conversations and figuring out how we can accomplish some of these goals that you and I both have. It has been such a pleasure to talk to you. You can call on me anytime. I’m always here.”

JFK: “Thank you so much.”

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

R29Unbothered continues its look at Black culture’s tangled history of Black identity, beauty, and contributions to the culture. In 2021, we’re giving wings to our roots, learning and unlearning our stories, and celebrating where Black past, present and future meet.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Life After Black Squares: Who Kept Their Promises?