When did you last wear a bra? Perhaps you’re perturbed by the question – you have one on right now, of course. Or has it become occasion wear, slung on for Zoom meetings, date nights at the dining table or, thrillingly, just for the sake of it when venturing into the outside world for groceries. Maybe, like me, you’re not quite sure when you last put one on and couldn’t even say where most of yours now are – I think at least three of mine have been inadvertently kicked under the bed to gather dust and cat hair.

The question of bras in lockdown has been a contentious one. Tweets abound from those enjoying quarantine sans bra, struggling to imagine a return to a fully dressed, partially underwired world. A mild rash of articles based on disproven scientific claims has emerged, questioning whether prolonged periods of bralessness will lead to breast sagging (short answer: no, the only real worry is for those with fuller busts whose bras offer significant support and help to ease back pain). Elsewhere statistics point to some fascinating – and contrary – consumer behaviours. Lingerie sales are rocketing: lacy and racy varieties have enjoyed a significant leap, while sales of Calvin Klein’s soft cup style at Selfridges have risen by 70%.

For those of us not using this time to stock up on underwear, the question of bras, or bralessness, is also a question of nipples. Besides hoicking up and holding one’s boobs in place, and generally shaping the silhouette, a bra also tends to hide one’s nipples (unless it is made from a very sheer or flimsy fabric). To go without is to accept that one’s areolae may be partially visible. That shouldn’t really be a big deal but sometimes, for a number of longstanding and gendered reasons, it still is. Eight years after Lina Esco spearheaded the Free the Nipple movement, a woman’s bare breast is still censored on Instagram – an obvious double standard that only highlights the platform’s binary and outdated approach to gender.

Much of this contention is the result of the various loaded meanings bestowed on breasts throughout history. Whether maternal and life-giving, brimming with erotic potential or subject to highly uncomfortable objectification, they have never been a particularly neutral body part. A cursory look at representations of the nipple in popular culture tells a conflicting tale of motherhood and sexuality, with an eclectic range of references: Renaissance portraits of the Madonna and Child; paintings of 18th-century French aristocracy, nipples peeking out above embellished necklines; images of catwalk models swathed in translucent fabric; Ellen Von Unwerth’s highly sexualised photoshoots.Let’s return for a moment to those 18th-century dresses. At many points throughout this complicated history the nipple has formed a consciously chosen element of an outfit – to decorative and political ends. Émilie du Châtelet, born in 1706, was a natural philosopher and mathematician who is now remembered – somewhat frustratingly – for her role as Voltaire’s mistress. She was also known contemporaneously for her penchant for low-cut dresses that revealed her nipples, which she rouged to accentuate their appearance – the same attention we might give our eyes or cheeks today. She wasn’t an anomaly either. The fashion for tight bodices that cantilevered breasts into a position where the nipple might be visible proved popular. In an era where breasts didn’t always have the immediately eroticised connotations that they do today, they formed an intriguing accessorising possibility.

Sometimes their desired effect was obvious. Pauline Bonaparte, sister of Napoleon, was born in 1780 and had a taste for scandal. Not only did she allegedly commission a gold cup in the shape of her breast – a truly artisanal form of exhibitionism – but she too rouged her nipples and is said to have revelled in others’ responses to her sheer dresses.

Ping forward several centuries and the nipple took on another meaning. Protests at the Miss America pageant in 1968 have since entered the realms of the mythic, marking the moment when bra-burning became associated with the feminist movement. However this is tired cliché rather than accurate history. Although protestors outside the event did throw items which they saw as symbolic of female oppression – including bras, makeup and high heels – into a ‘freedom trash can’, they were never set alight as often alleged. The 1960s did spur a rejection of bras within the women’s liberation movement though, given their discomfort and uneasy association with patriarchal restriction. In this context, a nipple glimpsed beneath clothing could be read as a fierce refusal of propriety. To others it became a new kind of fashion statement. Sixties hippyish ideals and ’70s loose silhouettes (not to mention disco fever) embraced bralessness, suggesting a blithe, undone glamour that was epitomised by the likes of Jane Birkin, Bianca Jagger and Marisa Berenson.

PHOTO BY DAVE BENETT/CONTRIBUTOR/GETTY IMAGESIt was in the ’90s, though, that nipples really went mainstream. Madonna famously bared hers in a Jean-Paul Gaultier harness at the designer’s 1992 amfAR fundraiser in Los Angeles. Kate Moss regularly wore sheer slips and barely there dresses, and plenty of her supermodel peers walked in shows for YSL, John Galliano, Prada and Alexander McQueen (among others), their breasts either partially or fully revealed. Following on from her ‘Tits’ T-shirt of the ’70s – now part of the collection at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art – Vivienne Westwood continued to nod to the historic eras she regularly raided for inspiration, designing low-cut bodices that squashed the wearer’s boobs into the revealing territory of those 18th-century rouged nipple devotees.ADVERTISEMENT

On TV, too, nipples featured prominently. Think Debra Messing on Will and Grace, the cast of Sex and the City (preceding, of course, Samantha’s stick-on nipples of season 4) and, perhaps most significantly, Rachel on Friends. Through relationship mishaps, ill-advised cat purchases and many, many hours in Central Perk, Jennifer Aniston’s nipples formed a strangely integral part of her character’s wardrobe, complementing a rotation of tight tanks, sleeveless turtlenecks, cropped jumpers and V-necks. The prevalence of the nipple on late ’90s TV screens might be explained by the narrow range of padded bras available at the time compared to our present abundance of choice. But it also embodies a particular cultural moment – one that championed sartorial freedom, comfort, tongue-in-cheek provocation, female independence, and thinness.With only a few exceptions, many of the examples here from across the historic spectrum fit into a category sometimes described as ‘fashion tits’. Fashion tits are small, perky and relatively unobtrusive. They do not always require a bra for practical reasons. They dovetail neatly with society’s generally narrow ideals of acceptability. Although still sexualised, they arguably escape some of the objectification endured by those with larger breasts. Fashion tits are often deemed more acceptable when fully visible through clothing or hinted at, à la Kate Moss, beneath a white T-shirt.Many of the current crop of famous figures could be said to embody this kind of ’90s style and silhouette: the likes of Kendall Jenner, Bella Hadid, Dua Lipa, Zoë Kravitz, Miley Cyrus. Regularly cited in articles about the resurgence of the nipple in recent years (and invariably described in The Daily Mail as ‘flashing’, ‘flaunting’ and ‘leaving little to the imagination’ whenever they commit the crime of being a woman in public without a bra), they nonetheless fit a particular beauty mould. It is a mould whereby a visible nipple is a bodily fact rather than anything especially daring.

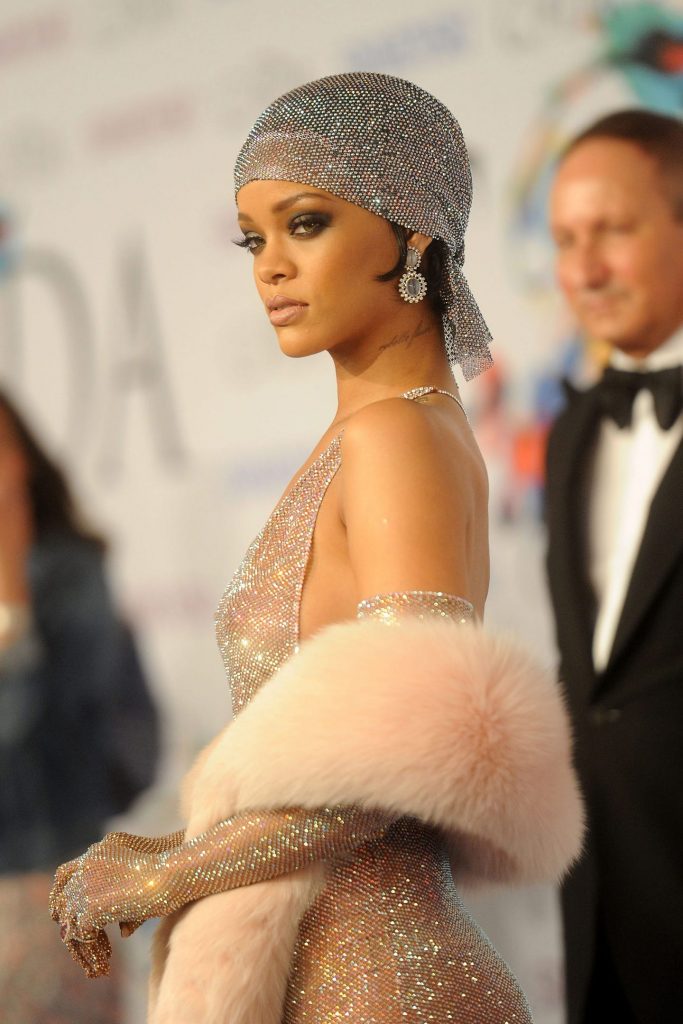

PHOTO BY JAMIE MCCARTHY/STAFF/GETTY IMAGESThere are other figures to think about, too, during these long, half-dressed days at home – not least patron saint of the nipple-as-fashion-statement, Rihanna. When she turned up at the CFDA awards in 2014, glittering from neck to ankle in a sheer gown, she asked one reporter: “Do my tits bother you? They’re covered in Swarovski crystals, girl!” Sitting here in my grey American Apparel T-shirt, which I’ve worn twice this week already, that seems like a much more dazzling version of bralessness than any I’m currently experiencing.